The 6th International Workshop on Heavy Quarkonia took place in Nara in December 2008, attracting some 100 participants. It was the latest in a series organized by the Quarkonium Working Group (QWG), a collaboration of theorists and experimentalists particularly interested in research related to the physics of quarkonia – bound states of heavy quark–antiquark pairs (Brambilla et al. 2004). The talks and discussions in three round tables emphasized the latest advances in the understanding of quarkonium production, the discovery of the ηb, the properties of the X, Y and Z narrow resonances, as well as the use of quarkonium states as probes of the QCD matter formed in high-energy nuclear collisions. The meeting ended with a series of talks about how the Antiproton Annihilations at Darmstadt (PANDA) experiment and the LHC experiments should improve and complement present knowledge.

New states

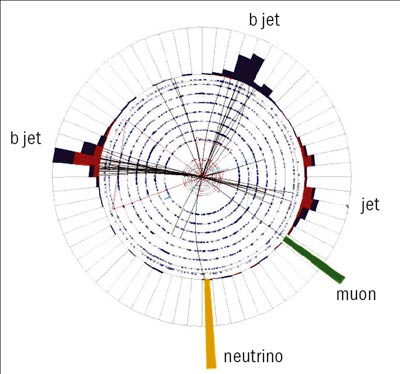

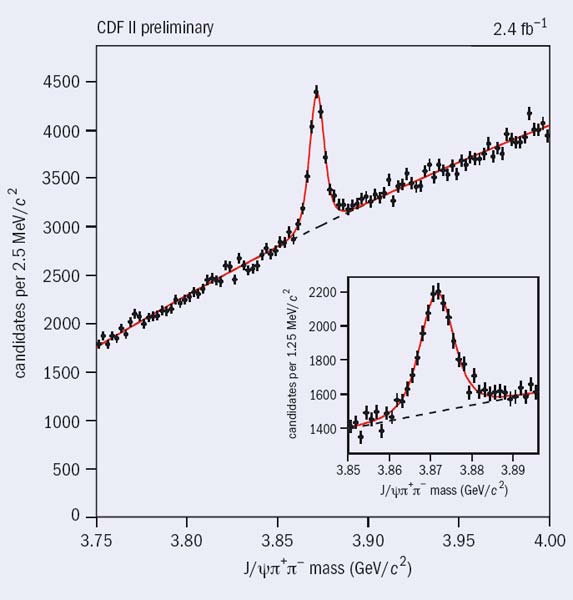

The nature and properties of the X, Y and Z narrow resonances, recently discovered in B-factories (and thought to be quarkonium states), were extensively discussed at the workshop. Presentations from the Belle, BaBar and CDF collaborations provided new information on the masses, branching ratios, quantum numbers and production properties of these particles. Using approximately 6000 signal events in J/ψ → π+π– decays, CDF obtained the most precise determination of the X(3872) mass: 3871.61±0.16(stat.) ±0.19(syst.) MeV/c2, a value extremely close to the D0D*0 mass threshold, 3871.8±0.36 MeV/c2 (figure 1). Given present uncertainties, the interpretation of the X(3872) as a “molecular” D0D*0 bound state remains possible but not compulsory. In addition the CDF collaboration reported a very accurate mass measurement for the Bc± of 6275.6±2.9(stat.) ±2.5(syst.) MeV/c2, obtained by studying the mass spectrum of Bc+ → J/ψπ+ decays (and the charge conjugates). The CDF and D0 experiments also measured the Bc lifetime, through the study of semileptonic decays. The measurements are of comparable precision, leading to a world average lifetime of 0.459±0.037 ps for the only observed charged quarkonium.

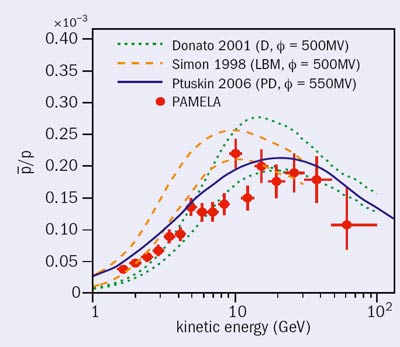

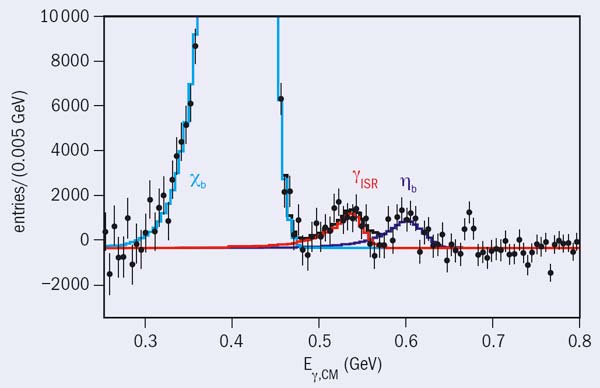

Another hot topic was the BaBar experiment’s discovery of the long-sought-after bottomonium ground state, the ηb. On the basis of a record amount of event samples collected early in 2008 (more than two hundred million U(2S) and U(3S) events), the BaBar collaboration announced in July the observation of the ηb in the rare magnetic-dipole transition U(3S) → γηb. At the Nara workshop, BaBar showed preliminary evidence for the U(2S) → γηb decay, which confirms the earlier observation (figure 2). The measured mass for the ηb is 71.4 (stat.) ±2.7(syst.) MeV smaller than the U(1S) mass. This mass difference is almost twice the value calculated in perturbative QCD, 39±11(theor.) (δαs) MeV, hence challenging the expectation that non-perturbative corrections should be only a few million electron-volts.

The Belle collaboration reported an improved measurement of the inclusive cross-section for the production of a J/ψ meson plus additional charmed particles. The new result is around 15% lower than their previous value and, in combination with a new calculation of next-to-leading-order (NLO) corrections, brings theory and experiment into reasonable agreement – albeit with large uncertainties – potentially solving a long-standing quarkonium-production puzzle.

The workshop also heard about new calculations of NLO corrections to the colour-singlet quarkonium-production mechanism, which confirm that the ratio between the colour-singlet and colour-octet production rates is larger than previously thought. The same calculations predict that J/ψs produced via the colour-singlet mechanism should exhibit a stronger longitudinal polarization in the helicity frame than is observed in the data from CDF. In the case of J/ψ photoproduction, new NLO calculations of the colour-singlet contribution fail to reproduce the polarization measurements made at HERA. If it turns out that feed-down effects do not modify the observed polarizations significantly then these discrepancies might indicate that a colour-octet contribution is required to bring the polarization predictions and experiment into agreement. There was also a discussion on the consistency of the measurements of the J/ψ polarization by the E866, HERA-B and CDF experiments. The seemingly contradictory data sets are surprisingly well reproduced if one models the polarization along the direction of relative motion of the colliding partons by assuming that, for directly produced J/ψs, it changes continuously from fully longitudinal at low total momentum to fully transverse at asymptotically high total momentum.

Heavy ions

Another interesting line of research in the QWG’s activities has to do with the use of heavy-quarkonium states as particularly informative probes of the properties of the high-density QCD matter produced in high-energy heavy-ion collisions. Contrary to early expectations, however, currently available J/ψ suppression measurements cannot be seen as “smoking-gun signatures” that would show beyond reasonable doubt the creation of a deconfined state of quarks and gluons. Indeed, the present experimental picture is blurred by several “cold nuclear matter” effects, including shadowing of the parton densities, final-state nuclear absorption of fully formed charmonium states (or of pre-resonances) and initial-state parton-energy loss. Furthermore, there needs to be a careful evaluation of feed-down contributions to the production yields of the J/ψs (and their own “melting” patterns). Presentations in Nara showed recent progress in the understanding of these topics and there were detailed discussions concerning the quarkonium properties in finite-temperature QCD. Future measurements of the U family at the LHC should open a better window into this interesting landscape.

Image credit: Kenkichi Miyabayashi.

The next International Workshop on Heavy Quarkonia will take place at Fermilab in May 2010. Meanwhile, quarkonium aficionados are eagerly awaiting the first results from the LHC. More than 30 years after the serving of the charmonium and bottomonium families as revolutionary entrées, quarkonium physics remains high in the menus of many physicists, providing a table d’hôte where to test the properties of perturbative and non-perturbative QCD and validate the continually improving computational tools. Sprinkled with enough puzzles to spice up the meal, quarkonium physics will continue to please the most discerning appetites for years to come.