In August, some 100 physicists will gather at Bad Saarow in Germany to celebrate the centenary of the discovery of cosmic rays by the Austrian scientist, Victor Hess. The meeting place is close to where Hess and his companions landed following their flight from Aussig during which they reached 5000 m in a hydrogen-filled balloon; Health and Safety legislation did not restrain them. Finding the rate of ion-production at 5000 m to be about three times that of sea level, Hess speculated that the Earth’s atmosphere was bombarded by high-energy radiation. This anniversary might also be regarded as the centenary of the birth of particle physics. The positron, muon, charged pions and the first strange particles were all discovered in cosmic rays between 1932 and 1947; and in 1938 Pierre Auger and colleagues showed, by studying cascade showers produced in air, that the cosmic-ray spectrum extended to at least 1015 eV, a claim based on the new ideas of QED.

Reviewing history, one is struck by how reluctant physicists were to contemplate particles other than protons, neutrons, electrons and positrons. The combination of the unexpectedly high energies and uncertainties about the validity of QED meant that flaws in the new theory were often invoked to explain observations that were actually evidence of the muon. Another striking fact is how many giants of theoretical physics, such as Bethe, Bhabha, Born, Fermi, Heisenberg, Landau and Oppenheimer, speculated on the interpretation of cosmic-ray data. However, in 1953, following a famous conference at Bagnères de Bigorre, the focus of work on particle physics moved to accelerator laboratories and despite some isolated discoveries – such as that of a pair of particles with naked charm by Kiyoshi Niu and colleagues in 1971, three years before the discovery of the J/ψ at accelerators – accelerator laboratories were clearly the place to do precision particle physics. This is not surprising because the beams there are more intense and predictable than nature’s: the cosmic-ray physicist cannot turn to the accelerator experts for help.

Cosmic rays remained – and remain – at the energy frontier but post-1953 devotees were perhaps over eager to show that particle-physics discoveries could be made with cosmic rays without massive collaborations. Cosmic-ray physicists preferred to march to the beat of their own drums. This led to attitudes that were sometimes insufficiently critical and the field became ignored or even mocked by many particle physicists. In the 30 years after Bagnères de Bigorre, a plethora of observations of dramatic effects were claimed, including Centauros, the Mandela, high-transverse momentum, the free quark, the monopole, the long-flying component and others. Without exception, these effects were never replicated because better cosmic-ray experiments were made or the relevant energies were superseded at machines. That many of the key results – good and bad – were hidden in the proceedings of the biennial International Cosmic Ray Conference did not help. Not that the particle-physics community has never made false claims: older readers will recall that in 1970 the editor of Physical Review Letters found it necessary to lay down “bump hunting” rules for those searching for resonances and, of course, the “split A2”.

However, another cosmic-ray “discovery” led to a change of scene. In 1983, a group at Kiel reported evidence for gamma rays of around 1015 eV from the X-ray binary, Cygnus X-3. Their claim was apparently confirmed by the array at Haverah Park in the UK and at tera-electron-volts energies at the Whipple Telescope in the US. Several particle physicists of the highest class were sucked into the field by the excitement. This led to the construction of the VERITAS, HESS and MAGIC instruments that have now created a new field of gamma-ray astronomy at tera-electron-volt energies. The construction of the Auger Observatory, the largest cosmic-ray detector ever built, is another major consequence. In addition to important astrophysics results, the instrument has provided information relevant to particle physics. Specifically, the Auger Collaboration has reported a proton–proton cross-section measurement at a centre-of mass energy of 57 TeV.

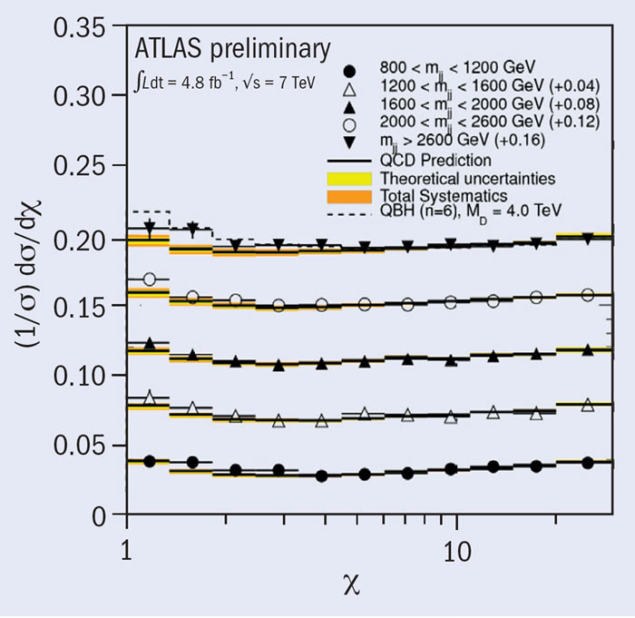

When the LHC began to explore the tera-electron-volt energy region, some models used by cosmic-ray physicists were found to fit the first rapidity-data as well as, if not better than, those from the particle-physics theorists. It is clear that there is more to be learnt about features of hadronic physics through studying the highest-energy particles, which reach around 1020 eV. Estimates of the primary energy that are made using hadronic models are significantly higher than those from the measurements of the fluorescence-light from air-showers, which give a calorimetric estimate of the energy that is almost independent of assumptions about particle physics beyond the LHC. Furthermore, the number of muons found in high-energy showers is about 30% greater than predicted by the models. The Auger Collaboration plans to enhance their instrument to extend these observations.

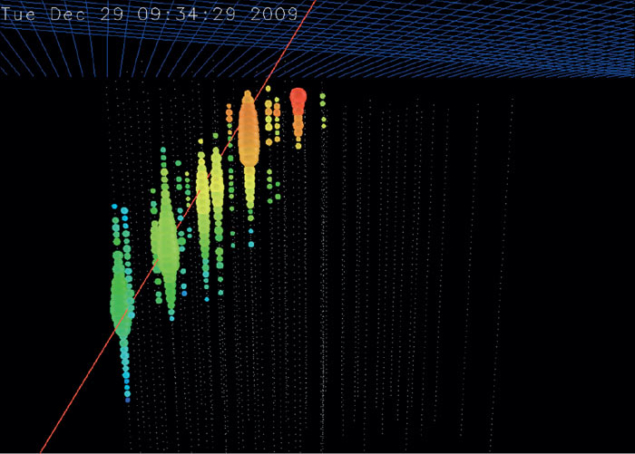

Towards the end of operations of the Large Electron–Positron collider at CERN, projects such as L3-Cosmics used the high-resolution muon detectors to measure muon multiplicities in showers. Now there are plans to do something similar through the ACME project, part of the outreach programme related to the ATLAS experiment at the LHC, but with a new twist. The aim is for cheap shower detectors of innovative design, paid for by schools, to be built above ATLAS – with students monitoring performance and analysing data. Overall, we are seeing another union of cosmic-ray and particle physics, different from that of pre-1953 but nonetheless one that promises to be as rich and fascinating.