Image credit: IceCube collaboration.

Neutrino experiments – thanks to the nature of the particles themselves – are notoriously difficult and experiments that make use of the natural source of particles within the cosmic radiation face problems of their own. In detecting cosmic neutrinos, the IceCube Neutrino Observatory at the South Pole successfully contends with both of these challenges, as two papers to appear in Physical Review Letters reveal. They illustrate the observatory’s capabilities in particle physics and in astroparticle physics.

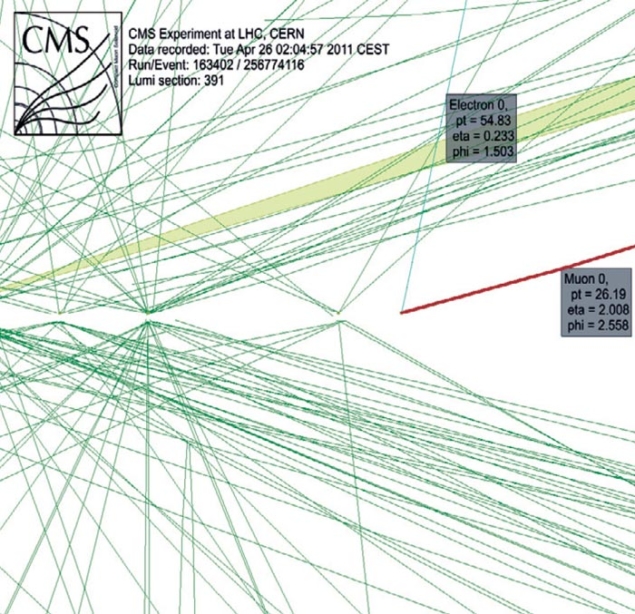

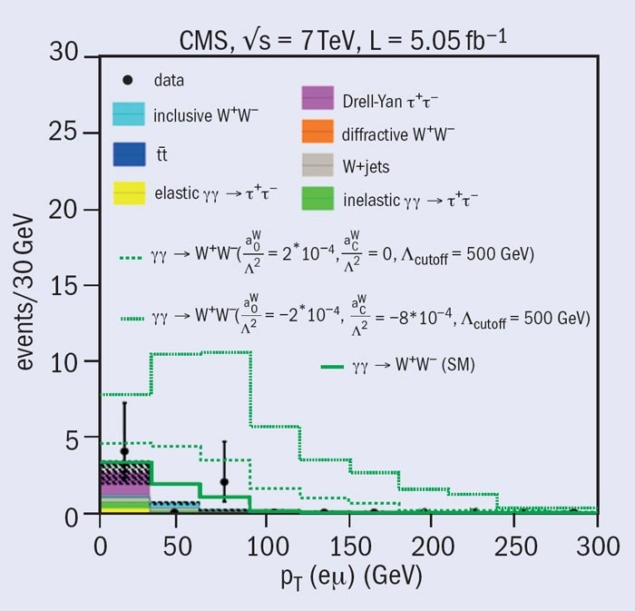

The potential for IceCube to meet its aim of detecting neutrinos from astrophysical sources has been boosted by the observation of two neutrino events with the highest energies ever seen. The events have estimated energies of 1.04±0.16 and 1.14±0.17 PeV – hundreds of times greater than the energy of protons at the LHC. The expected number of atmospheric background events at these energies is 0.082±0.004 (stat.)+0.04–0.057 (syst.) and the probability that the two observed events are background is 2.9 × 10–3, giving the signal a significance of 2.8σ (Aartsen et al. 2013a). While this is not sufficient to indicate a first observation of astrophysical neutrinos, the closeness in energy of the two events is intriguing and is already attracting the attention of theorists.

The analysis revealed the disappearance of low-energy, upwards-moving muon neutrinos and rejected the non-oscillation hypothesis with a significance of more than 5σ

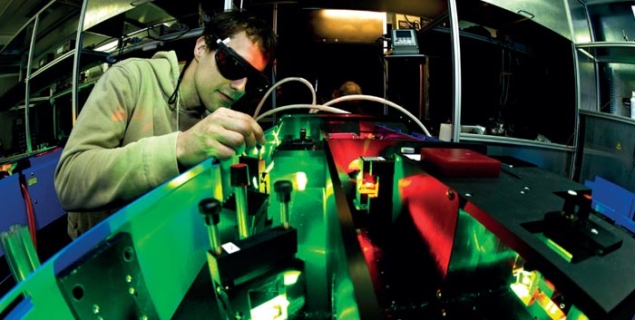

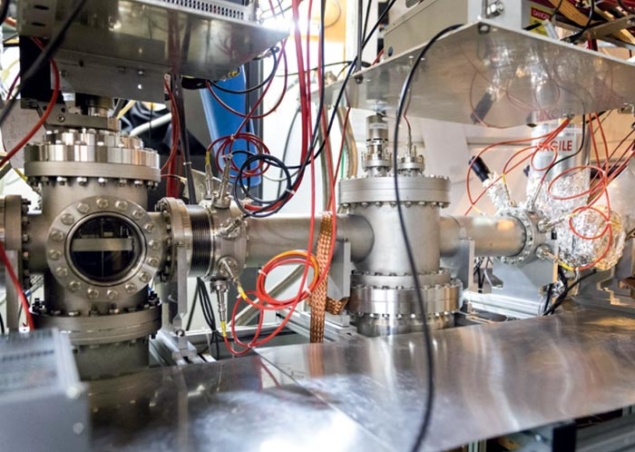

Meanwhile, measurements of lower-energy neutrinos produced in the atmosphere have enabled the IceCube collaboration to make the first statistically significant detection of neutrino oscillations in the high-energy region (20–100 GeV). The data used for this analysis were collected between May 2010 and May 2011 by the IceCube and DeepCore detectors, which together make up the IceCube Neutrino Observatory. The IceCube detector consists of an array with 86 strings of digital sensors deployed in Antarctica’s ice sheet at depths in the range 1450–24507 m. This main array defines the high-energy detector, designed to detect neutrinos with energies from hundreds to millions of giga-electron-volts – that is, up to the peta-electron-volts and more of the observed high-energy events. The DeepCore subdetector adds eight additional strings near the centre of this array, six of which were deployed during the period covered by this analysis. The denser core allows lowering the energy threshold to about 20 GeV.

The analysis revealed the disappearance of low-energy, upwards-moving muon neutrinos and rejected the non-oscillation hypothesis with a significance of more than 5σ. This result verifies the first, lower-significance indication reported by the ANTARES collaboration. Using a two-neutrino flavour formalism, the IceCube collaboration derived a new estimation of the oscillation parameters, |Δm223| = 2.3+0.6–0.5 × 10–3 eV2 and sin22θ23 > 0.93, with maximum mixing favoured. These values are in good agreement with previous measurements by the MINOS and Super-Kamiokande experiments.

More efficient event-reconstruction methods are being tested, which together with new data sets will increase the sensitivity of the IceCube and DeepCore detectors to atmospheric neutrino oscillations. As a result of these improvements, the IceCube collaboration is expecting to set further constraints on the oscillation parameters in the coming months.