Image credit: AEC.

Aristotle said that ‘‘An iron ball of one hundred pounds, falling from a height of one hundred cubits [about 5.2 m], reaches the ground before a one-pound ball has fallen a single cubit.” Galileo Galilei replied, “I say that they arrive at the same time.” The universality of free fall illustrated by the latter’s legendary experiment at the tower of Pisa was formulated by Isaac Newton in his Principia and became, with Albert Einstein, the weak equivalence principle (WEP): the motion of any object under the influence of gravity does not depend on its mass or composition. This principle is the cornerstone of general relativity.

The WEP has been verified to incredible precision by dropping experiments and Eötvös-type torsion balances, the latter reaching an amazing accuracy of one part in 1013. The acceleration of the Earth and the Moon towards the Sun has also been determined to the same accuracy by measuring the transit time of laser pulses between the planet and the reflectors left on the Moon by the Apollo and Soviet space missions. But does the WEP also hold for antimatter for which no direct measurement has been performed, in particular for antimatter particles such as positrons or antiprotons? Or does antimatter even fall up?

The purpose of the 2nd International Workshop on Antimatter and Gravity, which took place on 13–15 November, was to review the experimental and theoretical aspects of antimatter interaction with gravity. The meeting was hosted by the Albert Einstein Center for Fundamental Physics of the University of Bern, following the success of the first workshop held in 2011 at the Institut Henri Poincaré in Paris. The highlights are summarized here.

Free-fall experiments with charged particles are notoriously difficult because they must be carefully shielded from electromagnetic fields

Free-fall experiments with charged particles are notoriously difficult because they must be carefully shielded from electromagnetic fields. For example, the sagging of the gas of free electrons in metallic shielding induces an electric field that can counterbalance the effect of gravity. Indeed, measurements based on dropping electrons led to a value of the acceleration of gravity, g, consistent with zero (instead of g = 9.8 m/s2). A free-fall experiment with positrons has not yet been performed, owing to the lack of suitable sources of slow positrons. In the 1980s, a team proposed a free-fall measurement of g with antiprotons at CERN’s Low Energy Antiproton Ring (LEAR), but it could not be performed before the closure of LEAR in 1996.

Using neutral antimatter such as antihydrogen can alleviate the disturbance from electromagnetic fields. The ALPHA collaboration at CERN’s Antiproton Decelerator (AD) has set the first free-fall limit on g with a few hundred antihydrogen atoms held for more than 400 ms in an octupolar magnetic field. The results exclude a ratio of antimatter to matter acceleration larger than 110 (normal gravity) and smaller than −65 (antigravity). Plans to measure this ratio at the level of 1% by using a vertical trap are under way.

Positronium matters

The AEgIS collaboration at the AD uses positronium produced by bombarding a nanoporous material with a positron pulse derived from a radioactive sodium source. Positronium (Ps) is then brought to highly excited states with lasers and mixed with captured antiprotons to produce antihydrogen (H) through the reaction Ps + p → e– + H. The highly excited antihydrogen atoms possess large electric dipole moments and can be accelerated with inhomogeneous electric fields to form an antihydrogen beam. The sagging of the beam over a distance of typically 1 m is measured with a two-grating deflectometer by observing the intensity pattern with high-resolution (around 1 μm) nuclear emulsions. AEgIS is currently setting up, with antiprotons (around 105) and positrons (3 × 107) successfully stacked. A first measurement of g is planned in 2015 and the initial goal is to reach 1% uncertainty.

As a neutral system, positronium is also suitable for gravity measurements, but free-fall experiments are not easy because positronium lives for 140 ns only. Such studies require sufficiently cold positronium in long-lived, highly excited states and the appropriate atom optics. Preparations for a free-fall experiment at University College London are under way.

At ETH Zurich, a team is measuring the 1s → 2s atomic transition in positronium with a precision better than one part per billion (1 ppb) by using a high-intensity positron beam that traverses a solid neon moderator and impinges on a porous silica target. The positronium ejected from the target is laser-excited to the 2s state and the γ-decay rate is measured by scintillating crystals, as a function of laser frequency. The 1s → 2s frequency can be calculated from hydrogen data. For hydrogen, the frequency is redshifted in the gravitational potential of the Sun, but the shift cannot be observed because the clocks used to measure the frequency are equally redshifted. However, for positronium (equal amounts of matter and antimatter) and assuming antigravity, measurements should yield a higher frequency than is calculated from hydrogen. At the level of 0.1 ppb, such studies could even test the hypothesis of antigravity as the Earth revolves around the Sun.

A similar experiment with muonium – an electron orbiting a positive muon – is planned at PSI in Switzerland. Ultra-slow muon beams with sub-millimetre sizes and sub-electronvolt energy for re-acceleration could also be used in a free-fall experiment employing gratings (a Mach–Zehnder interferometer).

Free-fall experiments

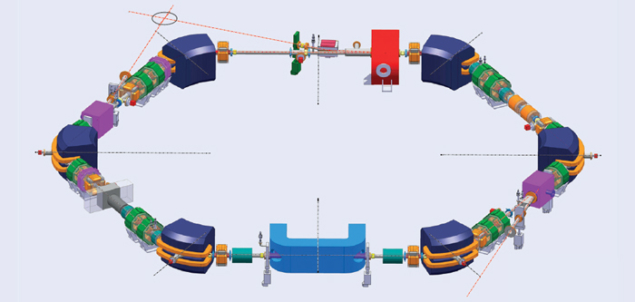

At CERN, the AD delivers bunches of 5.3 MeV antiprotons (3 × 107) every 100 s. However, storing antiprotons requires lower energies, which are reachable by inserting thin foils, albeit at the expense of substantial losses and degradation in beam size. Prospects for improved experiments are now bright with ELENA, a 30 m circumference electron-cooled ring that decelerates the AD beam further to 100 keV (figure 1). ELENA will be installed in 2015 and will be available for physics in summer 2017.

Image credit: ELENA team.

The first free-fall experiment to profit from this new facility will be GBAR. Antihydrogen atoms will be obtained by the interaction of antiprotons from ELENA with a positronium cloud. The positrons will be produced by a 4.3 MeV electron linac. In contrast to AEgIS, the antihydrogen atom will capture a further positron to become a positively charged ion, which can be transferred to an electromagnetic trap, cooled to 10 mK with cold beryllium ions and then transported to a launching trap where the additional positron will be photodetached. The mean velocity of the antihydrogen atoms will be around 1 m/s and the fall distance will be about 30 cm. GBAR will be commissioned in 2017 with the initial goal of reaching 1% accuracy on g.

The sensitivity of GBAR, limited by the velocity distribution of the antihydrogen atoms, could be improved substantially by using quantum reflection, a fascinating effect that was discussed at the workshop. Antihydrogen atoms dropped towards a surface experience a repulsive force, which leads to gravitational quantum states. A similar phenomenon was observed with cold neutrons at the Institut Laue–Langevin (ILL) in Grenoble. Now, the ILL team proposes to bounce the atoms in GBAR between two layers – a smooth lower surface to reflect slow enough antihydrogen atoms and a rough upper surface to annihilate the fast ones. Transition frequencies between the gravitational levels – which depend on g – could also be measured by recording the annihilation rate on the bottom surface. Provided that the lifetime of these antihydrogen levels is long enough, orders of magnitude improvements could be obtained on the determination of g.

Atom interferometers might be able to measure g to within 10–6. In a Ramsey–Bordé interferometer, the falling atom interacts with pulses from two counter-propagating vertical laser beams. Having absorbed a photon from the first beam, the atom is stimulated to emit another photon with the frequency of the second beam, thereby modifying its momentum. The signal from the annihilating antihydrogen atom, for example at the top of the interferometer, interferes with the one from another atom that has equal momentum but was not subject to the laser kick. The interference pattern will depend on the value of g.

At FLAIR the antiproton flux will be an order of magnitude higher than at ELENA

In the more distant future, the Facility for Low-energy Antiproton and Ion Research (FLAIR) will become operational at GSI. As an extension to the high-energy antiproton facility, FLAIR will consist of a low-energy storage ring decelerating antiprotons from 30 MeV to 300 keV, followed by an electrostatic ring capable of reducing the energy even further, down to 20 keV. At FLAIR the antiproton flux will be an order of magnitude higher than at ELENA, and slow extracted antiproton beams will be available for experiments in nuclear and particle physics.

The question of how large an effect these free-fall experiments could measure cannot be answered without theoretical assumptions, such as exact symmetry between matter and antimatter (the CPT theorem). However, string theory can break CPT. The standard model extension proposed by the Indiana/Carleton group involves Lorentz and CPT violation. Also, atoms and nuclei contain virtual antiparticles in amounts that depend on the atomic number. The calculable quantum corrections agree with measurements, arguing against antigravity. However, there is a huge discrepancy in the value of the cosmological constant estimated from vacuum particle–antiparticle pair fluctuations, which might question our understanding of the interaction between gravity and virtual particles. As pointed out at the workshop, if all of the theoretical assumptions are valid, then antimatter experiments should not expect to see discrepancies in g at a level larger than 10–7. Ultimately, the issue must be settled by experiments.

To compare with matter, a presentation was given on the 10–9 precision achievable on g at the Swiss Federal Institute of Metrology (METAS) using a free-fall interferometer. Together with improved measurements of Planck’s constant with a watt balance, this might lead to a re-definition of the kilogram based on natural units.

The workshop also included a session on antimatter in the universe. Is there any antimatter and could it repel matter (the Dirac–Milne universe) and provide the accelerating expansion? Can the excess of positrons observed above 10 GeV by balloon experiments, the PAMELA satellite experiment and, more recently, the Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope and the Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer (AMS-02), be explained by antimatter annihilation?

In his summary talk, Mike Charlton of Swansea University concluded that “the challenge of measuring gravity on antihydrogen remains formidable”, but that “in the past decade the prospects have advanced from the totally visionary to the merely very difficult”.

The workshop, with 28 plenary talks, was attended by 70 participants. A visit to the house where Einstein spent the years 1903–1905 and dinner at Altes Tramdepot were part of the social programme.