Image credit: CERN.

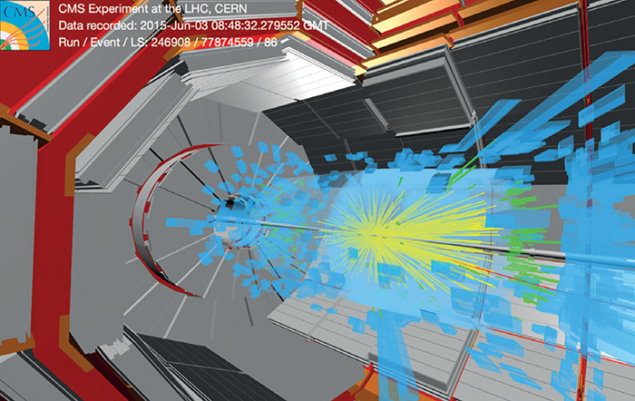

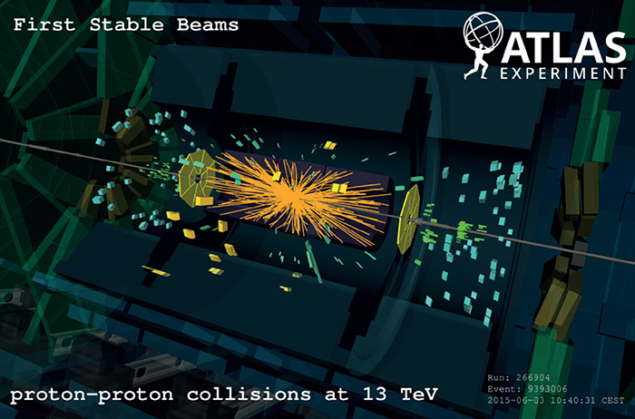

At 10.40 a.m. on 3 June, the LHC operators declared “stable beams” for the first time at a beam energy of 6.5 TeV. It was the signal for the LHC experiments to start taking physics data for Run 2, this time at a collision energy of 13 TeV – nearly double the 7 TeV with which Run 1 began in March 2010. After a shutdown of almost two years and several months re-commissioning without and with beam, the world’s largest particle accelerator was back in business. Under the gaze of the world via a live webcast and blog, the LHC’s two counter-circulating beams, each with three bunches of nominal intensity (about 1011 protons per bunch), were taken through the full cycle from injection to collisions. This was followed by the declaration of stable beams and the start of Run 2 data taking.

Image credit: CERN-PHOTO-201506-125-59.

The occasion marked the nominal end of an intense eight weeks of beam commissioning (CERN Courier May 2015 p5 and June 2015 p5) and came just two weeks after the first test collisions at the new record-breaking energy. On 20 May at around 10.30 p.m., protons collided in the LHC at 13 TeV for the first time. These test collisions were to set up various systems, in particular the collimators, and were established with beams that were “de-squeezed” to make them larger at the interaction points than during standard operation. This set-up was in preparation for a special run for the LHCf experiment (“LHCf makes the most of a special run”), and for luminosity calibration measurements by the experiments where the beams are scanned across each other – the so-called “van der Meer scans”.

Image credit: CERN-PHOTO-201506-131-9.

Progress was also made on the beam-intensity front, with up to 50 nominal bunches per beam brought into stable beams by mid-June. There were some concerns that an unidentified obstacle in the beam pipe of a dipole in sector 8-1 could be affected by the higher beam currents. This proved not to be the case – at least so far. No unusual beam losses were observed at the location of the obstacle, and the steps towards the first sustained physics run continued.

Image credit: CERN.

The final stages of preparation for collisions involved setting up the tertiary collimators (CERN Courier September 2013 p37). These are situated on the incoming beam about 120–140 m from the interaction points, where the beams are still in separate beam pipes. The local orbit changes in this region both during the “squeeze” to decrease the beam size at the interaction points and after the removal of the “separation bumps” (produced by corrector magnets to keep the beams separated at the interaction points during the ramp and squeeze). This means that the tertiary collimators must be set up with respect to the beam, both at the end of the squeeze and with colliding beams. In contrast, the orbit and optics at the main collimator groupings in the beam-cleaning sections at points 7 and 3 are kept constant during the squeeze and during collisions, so their set-up remains valid throughout all of the high-energy phases.

Image credit: CERN-PHOTO-201506-128-1.

By the morning of 3 June, all was ready for the planned attempt for the first “stable beams” of Run 2, with three bunches of protons at nominal intensity per beam. At 8.25 a.m, the injection of beams of protons from the Super Proton Synchrotron to the LHC was complete, and the ramp to increase the energy of each beam to 6.5 TeV began. However, the beams were soon dumped in the ramp by the software interlock system. The interlock was related to a technical issue with the interlocked beam-position monitor system, but this was rapidly resolved. About an hour later, at 9.46 a.m, three nominal bunches were once more circulating in each beam and the ramp to 6.5 TeV had begun again.

Image credit: ALICE/CERN OPEN-PHO-ACCEL-2015-007-15.

At 10.06 a.m., the beams had reached their top energy of 6.5 TeV and the “flat top” at the end of the ramp. The next step was the “squeeze”, using quadrupole magnets on both sides of each experiment to decrease the size of the beams at the interaction point. With this successfully completed by 10.29 a.m., it was time to adjust the beam orbits to ensure an optimal interaction at the collision points. Then at 10.34 a.m., monitors showed that the two beams were colliding at a total energy of 13 TeV inside the ATLAS and CMS detectors; collisions in LHCb and ALICE followed a few minutes later.

Image credit: CERN-PHOTO-201506-125-36.

At 10.42 a.m., the moment everyone had been waiting for arrived – the declaration of stable beams – accompanied by applause and smiles all round in the CERN Control Centre. “Congratulations to everybody, here and outside,” CERN’s director-general, Rolf Heuer, said as he spoke with evident emotion following the announcement. “We should remember this was two years of teamwork. A fantastic achievement. I am touched. I hope you are also touched. Thanks to everybody. And now time for new physics. Great work!”

Image credit: CMS-PHO-EVENTS-2015-004-3.

The eight weeks of beam commissioning had seen a sustained effort by many teams working nights, weekends and holidays to push the programme through. Their work involved optics measurements and corrections, injection and beam-dump set-up, collimation set-up, wrestling with various types of beam instrumentation, optimization of the magnetic model, magnet aperture measurements, etc. The operations team had also tackled the intricacies of manipulating the beams through the various steps, from injection through ramp and squeeze to collision. All of this was backed up by the full validation of the various components of the machine-protection system by the groups concerned. The execution of the programme was also made possible by good machine availability and the support of other teams working on the injector complex, cryogenics, survey, technical infrastructure, access, and radiation protection.

Image credit: ATLAS/CERN OPEN-PHO-ACCEL-2015-007-18.

Over the two-year shutdown, the four large experiments ALICE, ATLAS, CMS and LHCb also went through an important programme of maintenance and improvements in preparation for the new energy frontier.

Among the consolidation and improvements to 19 subdetectors, the ALICE collaboration installed a new dijet calorimeter to extend the range covered by the electromagnetic calorimeter, allowing measurement of the energy of the photons and electrons over a larger angle (CERN Courier May 2015 p35). The transition-radiation detector that detects particle tracks and identifies electrons has also been completed with the addition of five more modules.

Image credit: CERN-PHOTO-201506-130-32.

A major step during the long shutdown for the ATLAS collaboration was the insertion of a fourth and innermost layer in the pixel detector, to provide the experiment with better precision in vertex identification (CERN Courier June 2015 p21). The collaboration also used the shutdown to improve the general ATLAS infrastructure, including electrical power, cryogenic and cooling systems. The gas system of the transition-radiation tracker, which contributes to the identification of electrons as well as to track reconstruction, was modified significantly to minimize losses. In addition, new chambers were added to the muon spectrometer, the calorimeter read-out was consolidated, the forward detectors were upgraded to provide a better measurement of the LHC luminosity, and a new aluminium beam pipe was installed to reduce the background.

Image credit: ALICE-PHO-GEN-2015-003-10.

To deal with the increased collision rate that will occur in Run 2 – which presents a challenge for all of the experiments – ATLAS improved the whole read-out system to be able to run at 100 kHz and re-engineered all of the data acquisition software and monitoring applications. The trigger system was redesigned, going from three levels to two, while implementing smarter and faster selection-algorithms. It was also necessary to reduce the time needed to reconstruct ATLAS events, despite the additional activity in the detector. In addition, an ambitious upgrade of simulation, reconstruction and analysis software was completed, and a new generation of data-management tools on the Grid was implemented.

Image credit: LHCb/CERN OPEN-PHO-ACCEL-2015-007-11.

The biggest priority for CMS was to mitigate the effects of radiation on the performance of the tracker, by equipping it to operate at low temperatures (down to –20 °C). This required changes to the cooling plant and extensive work on the environment control of the detector and cooling distribution to prevent condensation or icing (CERN Courier May 2015 p28). The central beam pipe was replaced by a narrower one, in preparation for the installation in 2016–2017 of a new pixel tracker that will allow better measurements of the momenta and points of origin of charged particles. Also during the shutdown, CMS added a fourth measuring station to each muon endcap, to maintain discrimination between low-momentum muons and background as the LHC beam intensity increases. Complementary to this was the installation at each end of the detector of a 125 tonne composite shielding wall to reduce neutron backgrounds. A luminosity-measuring device, the pixel luminosity telescope, was installed on either side of the collision point around the beam pipe.

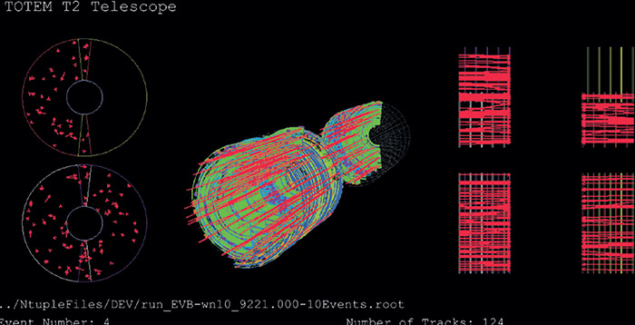

Image credit: TOTEM/CERN OPEN-PHO-ACCEL-2015-007-17.

Other major activities for CMS included replacing photodetectors in the hadron calorimeter with better-performing designs, moving the muon read-out to more accessible locations for maintenance, installation of the first stage of a new hardware triggering system, and consolidation of the solenoid magnet’s cryogenic system and of the power distribution. The software and computing systems underwent a significant overhaul during the shutdown to reduce the time needed to produce analysis data sets.

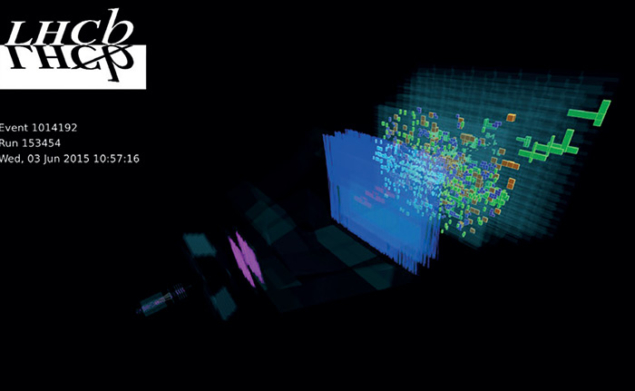

To make the most of the 13 TeV collisions, the LHCb collaboration installed the new HeRSCheL detector – High Rapidity Shower Counters for LHCb. This consists of a system of scintillators installed along the beamline up to 114 m from the interaction point, to define forward rapidity gaps. In addition, one section of the beryllium beam pipe was replaced and the new beam pipe support-structure is now much lighter.

The CERN Data Centre has also been preparing for the torrent of data expected from collisions at 13 TeV. The Information Technology department purchased and installed almost 60,000 new cores and more than 100 PB of additional disk storage to cope with the increased amount of data that is expected from the experiments during Run 2. Significant upgrades have also been made to the networking infrastructure, including the installation of new uninterruptible power supplies.

First stable beams was an important step for LHC Run 2, but there is still a long way to go before this year’s target of around 2500 bunches per beam is reached and the LHC starts delivering some serious integrated luminosity to the experiments. The LHC and the experiments will now run around the clock for the next three years, opening up a new frontier in high-energy particle physics.

• Complied from articles in CERN’s Bulletin and other material on CERN’s website. To keep up to date with progress with the LHC and the experiments, follow the news at bulletin.cern.ch or visit www.cern.ch.