Image credit: M Struik.

Massimo Tarenghi fell in love with astronomy at age 14, when his mother took away his stamp collection – on which he spent more time than on his schoolbooks – and gave him a book entitled Le Stelle (The Stars). By age 17, he had built his first telescope and become a well-known amateur astronomer, meriting a photo in the local daily newspaper with the headline “Massimo prefers a bigger telescope to a Ferrari.” Already, his dream was “to work at the largest observatory in the world”. That dream came true, because Massimo went on to build and direct the world’s most powerful optical telescope, the Very Large Telescope (VLT), at the European Southern Observatory (ESO)’s Paranal Observatory in Chile.

“I was born as a guy who likes to do impossible things and I like to do them 110%,” says Massimo, who decided to study physics at the University of Milan in the late 1960s “because [Giusepppe] Occhialini was the best in the world and allowed me to do a thesis in astronomy”. His road to the stars began in 1970, when he gained his PhD with a thesis on the production of gamma rays by Sagittarius A – at the time a mysterious radio source, which is now known to harbour the supermassive black hole at the centre of the Milky Way. This was at the time of the first observations in X rays and in infrared of the centre of the Galaxy, and the first of many examples of far-sighted intuition in Massimo’s career.

Following his PhD, Massimo convinced his colleagues at Milan to support the construction of an infrared telescope on the Gornergrat in the Swiss Alps. He was then sent to the Steward Observatory at the University of Arizona, where he did pioneering work in infrared astronomy. He quickly made himself known with a daring request for telescope time involving all of the instruments. “At that time,” he recalls, “there was a clear separation between astronomy for infrared, spectroscopy or photography, and there were three levels of use of an instrument: astronomer without assistant, assistant astronomer, or general (university) public. I asked for all of the instruments – and in particular for the bolometer, which no one had ever dared ask for!” After a three-hour meeting, his proposal to observe infrared galaxies was judged “very interesting but totally crazy”. So the committee suggested a compromise: 10 of his candidate objects would be observed during the telescope’s spare time and then they could review the request. Massimo accepted, and two weeks later seven of his objects had been found to be infrared emitters. “So they gave me the whole bolometer three-months later. I was lucky!” he says with the same enthusiasm as the 28-year-old postdoc he was at the time.

It was, once again, pure intuition. Massimo had chosen his 10 objects based on M82, a galaxy that interacts with its larger neighbour M81. “M82 is a beautiful galaxy with explosions and I thought, when two galaxies interact, they trigger explosions. So I simply had a collection of interacting galaxies and it came out that this is just what they did.” This intuition was to be confirmed by what has become a pillar of astrophysics: when two galaxies interact, the gas inside is compressed, creating a large number of new stars, which produce a large amount of infrared emission as they form.

Image credit: ESO/M Tarenghi.

While still in Arizona, Massimo decided to work on the optical identification of radio galaxies. “At the time, the Hercules cluster was not very well explored, with a redshift of 11,000 km/s. Compared to the well-known Coma cluster, with a redshift of 5000 km/s, it is much further and very difficult to observe between Arizona’s summer storms,” he explains. “Astronomers came to me saying that the cluster was ‘theirs’, as they had started work on it three years earlier. But they had done no observations. So I offered to collaborate, and we decided that whoever took more galaxies would be the first author on the publication. They found 19, I took all of the rest: 300.” That paper is now a cornerstone in astronomy. “It was the first time we saw clearly the existence of a void in the universe,” he continues. “There was no galaxy between 6000 and 9000 km/s. Today we know this void is the remnant of the Big Bang, the structure of the anisotropy of the universe recently observed by the Planck space telescope.”

Breaking records

Dubbing himself “a difficult person,” Massimo broke new ground not just in the way that astronomy is done, but by bringing innovation in the way that telescopes are conceived of and built. Intuition, determination and audacity are indeed the distinctive marks of his 35-year-long career at ESO, which he joined in 1977 as a member of the Science Group, when the organization was still based at CERN (CERN Courier October 2012 p26). He had decided to join ESO to observe with the largest European telescope – the 3.6 m, which was just being inaugurated at ESO’s site at La Silla in Chile.

“I obtained three nights for my cluster of galaxies in the Southern hemisphere,” he recalls, “but I was the second official user, during the first week of observation, and nobody knew if it was going to work. I received those three nights (plus three to compensate in case of problems) because I was the only one in Europe who had experience with big telescopes. I started to complain the first night and obtained the sixth night.” Massimo was then told that there would be another week of tests and he was asked if he would test the telescope, so he took the full week. “My colleagues were jealous but then were surprised that I really tested the telescope to adjust and calibrate it.” After these two weeks, he went back to Geneva and told ESO’s director that astronomers need to be associated with the construction of telescopes from the start. “So I created the role of ‘friend of instrument’ and for each instrument we associated one astronomer in charge,” he explains. The role of instrument scientist, commonplace now at the large telescopes worldwide, is thus Massimo’s invention.

Unsurprisingly, he then became project scientist for ESO’s next telescope, the 2.2 m. Built for the Max Planck Institute, it had been destined for Namibia originally, but with Italy and Switzerland about to join ESO in 1981, the decision was taken to install it at ESO’s site at La Silla. “The Italians are very aggressive astronomers,” Massimo explains, “so we needed to increase telescope time, and I was asked to take the 2.2 m telescope from Heidelberg, put it in place in La Silla, and run the team.” They had to do everything: they had no dome, no foundations, and a budget of only DM 5 million, which was a very limited amount compared with other projects of a similar size. But, as Massimo says, “when you have no money you do great things,” and he had an idea. “I saw a thin aluminium dome on the last page of an amateur astronomers’ magazine, and I asked an engineer in my team to design a scaled-down version of our dome.” With the concrete foundations laid almost manually, and the help of three engineers recruited from Zeiss to build a new electronic system, they succeeded in installing the telescope for a total cost of DM 7 million.

The 2.2 m telescope saw its first light in June 1983, with a record-breaking angular resolution of 0.6 arc seconds. “The reason is simple,” says Massimo. “The dome was so small that we had to move all the electronics underneath, so there was no source of heat coming from the telescope, and that’s how we learnt how to remove heat from the dome.” It was also the first telescope to be operated remotely. “We took the controls from the upper floor to the lower floor, and when we saw that it worked, with the software engineer we decided to do remote control from La Serena. Everybody was laughing, saying it would never work, but there was no reason it should not!” At the time, the connection was through a telephone line – not with optical fibre – and only in one direction. Massimo explains that when they needed somebody to close the dome on the other side, they used the phone to communicate from La Serena to La Silla. On the first occasion, he recalls, “I forgot the guy was still there. All night he was waiting for my call, and he waited five, six hours before he decided to call me, asking whether he could…go to the toilet!”

In 1983, Massimo was asked to be project manager for the New Technology Telescope (NTT), a 3.6 m optical telescope that saw first light six years later. With a record-breaking resolution of 0.33 arc seconds, it produced sharper images of stellar objects than ever obtained with a ground-based telescope. The NTT was the prototype for a new type of telescope that would make the VLT possible. The main revolutionary feature was the application of active optics, in which a thin and flexible primary mirror is kept in its correct shape by a support system that responds to continual real-time analysis of a stellar image. It was ESO’s Ray Wilson who invented the system, but Massimo was involved from early on, and his former institute in Milan built the first test bench with which the system was shown to work in the early 1980s. The thin-mirror technology allowed by active optics was the breakthrough that enabled the construction of the next generation of much larger telescopes, in particular the VLT, built on a second ESO site in Chile, on the mountain of Cerro Paranal in the Atacama desert.

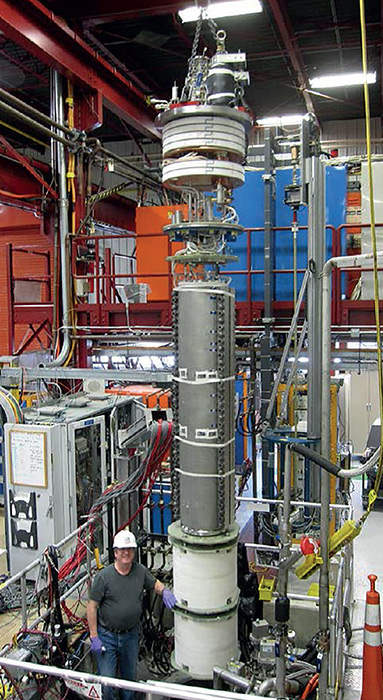

The VLT was proposed in 1986 and approved in 1987. Massimo was given the responsibility to build it in March 1988 by ESO’s director-general Herry van der Laan, and was later fully supported by the following director-general, Riccardo Giacconi. He was part of the team that decided to go from 4 m to 8 m mirrors that could be combined as an astronomical interferometer – a technique that was still in its early days. With four fixed 8.2 m-diameter Unit Telescopes (UTs) and four 1.8 m-diameter movable Auxiliary Telescopes (ATs), the VLT is today the most advanced optical observatory in the world. The UTs work either individually or in a combined mode using interferometry, while the ATs are entirely dedicated to interferometry. “I had under me 250 technicians. It was the craziest project I ever managed,” Massimo remembers, “and I learnt a lesson: if you want to work in the biggest observatory in the world you have to build it!”

Building the Paranal Observatory was not just a scientific experience for Massimo, he is at also at the origin of the award-winning futuristic Residencia, chosen as the set for the James Bond film Quantum of Solace. “I wanted something that could make astronomers at Paranal become human again after 13 or 14 hours of observation, to experience the pleasure of water, and of green, red and all the colours missing in the desert,” he explains. “This is the dream we recreated in this place, water in the desert, for the people working at the most advanced telescope in the world.”

After the VLT, Massimo went on to direct another “crazy” astronomy project, the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), the first truly global collaboration in astronomy (CERN Courier October 2007 p23). He also conducted the exploration work for the site of the next-generation facility, the European Extremely Large Telescope (E-ELT), with a record-breaking 39 m-diameter mirror. Construction work started at the Cerro Armazones, the chosen site for E-ELT, in March 2014. Massimo, who celebrated his 70th birthday at the end of July, officially retired from ESO in 2013, but he has not stopped working for European astronomy. He still commutes between the ESO sites in Chile, Santiago and Munich, supporting ESO’s public-relations activities in Chile – and spending endless nights photographing the unique sky above the Atacama desert.