Résumé

Une histoire de luminosité

Les résultats du programme du Tevatron ont largement dépassé les objectifs de physique prévus initialement, en raison notamment de l’augmentation d’un facteur 100 de la luminosité produite par rapport à ce qui était prévu au départ. Même avec une énergie fixe, les collisionneurs d’hadrons sont, à bien des égards, une source presque intarissable de physique. Le LHC a produit jusqu’ici environ 1 % de la luminosité attendue au total, situation similaire à celle du Tevatron en 1995, au moment de la découverte du quark top. Si les choses se passent comme avec le Tevatron, les expériences LHC nous offriront encore beaucoup de résultats exceptionnels !

Image credit: S Holmes and V Shiltsev.

Throughout history, the greatest instruments have yielded a treasure trove of scientific results and breakthroughs via long-term “exposures” to the landscape they were designed to study. Among many examples, there are telescopes and space probes (such as Hubble), land-based observatories (such as LIGO), and particle accelerators (such as the Tevatron and the LHC).

The long-lived nature of these explorations not only opens up the possibility for discovery of the rarest of phenomena with increases in the amount of the data collected, but also allows a narrower focus on specific regions of interest. In these sustained endeavours, the scientist’s ingenuity is unbounded, and through a combination of instrumental and data-analysis innovations, the programmes evolve well beyond their original scope and expected capabilities.

In 2015, the LHC increased its collision energy from 8 to 13 TeV, marking the start of what ought to be a long era of exploration of proton–proton collisions at the LHC’s design energy. In December 2015, both the CMS and the ATLAS experiments disclosed intriguing results in their di-photon invariant mass spectra, where an excess of events near 750 GeV suggest the possibility of a new and unexpected particle emerging from the data (CERN Courier January/February 2016 p8). With just a few inverse femtobarn of data recorded, the statistical significance of the observation is not sufficient to conclude if this is a coincidental background fluctuation or whether this might be a great new discovery. One thing is certain: more data are needed.

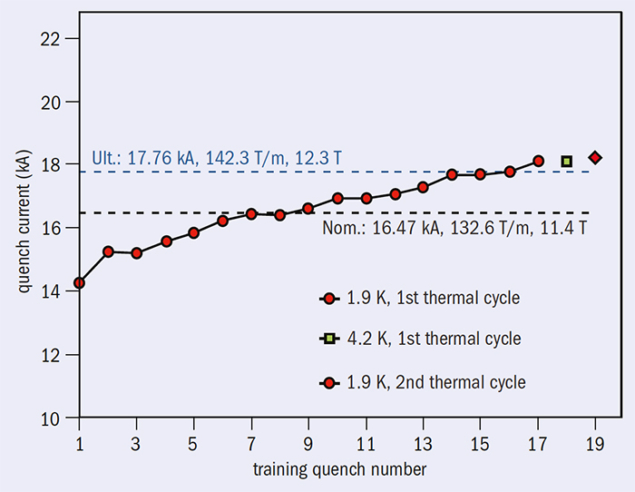

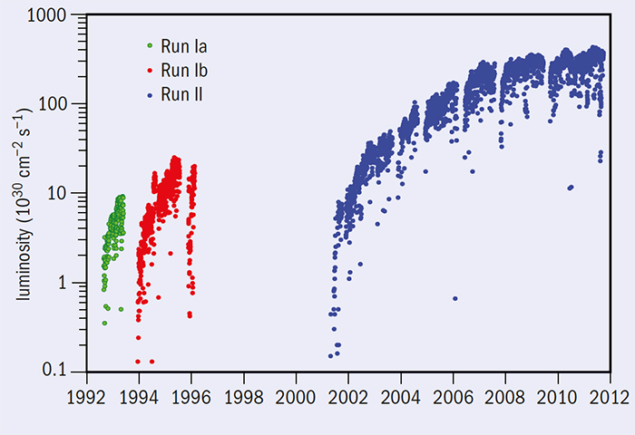

It is worth reflecting on the experience of the Tevatron collider programme, where proton–antiproton collisions at ~ 2 TeV centre-of-mass energy were accumulated during a 25 year period, from 1986 to 2011. During this time period, the Tevatron’s instantaneous luminosity increased from 1029 cm–2 s–1 to above 4 × 1032 cm–2 s–1 – exceeding by two orders of magnitude the original design luminosity. Figure 1 shows the progression of the initial luminosity for each Tevatron store (in each interaction region) versus time. Also shown in the figure are periods of no data during extended upgrade shutdowns. The luminosity growth was due to the construction of new large facilities, and due to upgrades and better use of the existing equipment. The steady growth of antiproton production was the cornerstone of the growth in luminosity. The construction of the facilities supporting the Tevatron’s luminosity growth included the Linac extension in the early 1990s that resulted in doubling its energy to 400 MeV and an increase of the Booster intensity; the construction of the Main Injector (150 GeV rapid-cycling proton accelerator) that greatly increased proton beam power for antiproton production; the construction of the Recycler ring made of permanent magnets and commissioned at the beginning of the 2000s added the third antiproton ring, which was helpful for an increase in the antiproton production rate; and a major upgrade of the stochastic cooling system for the antiproton complex and development and construction of the electron cooling in the 2000s reduced the antiproton beam emittances. A large number of other accelerator improvements were also key for the Tevatron ultimately delivering more than 10 fb–1 of luminosity to each of the two Tevatron general-purpose experiments, CDF and D0. All of them required deep insight into the underlying accelerator physics problems, inventiveness and creativity.

Image credit: The authors.

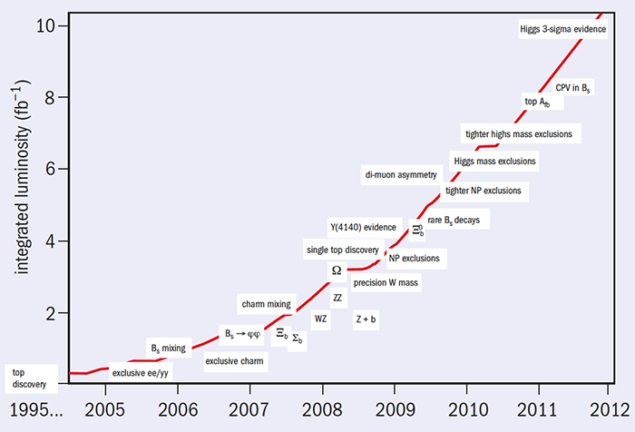

From the measurement of the charged-particle multiplicity in the first few proton–antiproton collisions to the tour-de-force that was the search for the Higgs boson with the full data set of ~10 fb–1, the CDF and D0 experiments harvested a cornucopia of scientific results. In the period from 2005 to 2013, the combined number of publications was constant at roughly 80 per year, with the total number of papers published using Tevatron data reaching 1200, with more coming.

The results from this bountiful programme include such fundamental results as the top-quark discovery and evidence for the Higgs boson, rare Standard Model processes (such as di-boson and single top-quark production), new composite particles (such as a new family of heavy b-baryons), and very subtle quantum phenomena (such as Bs mixing). The results also include many high-precision measurements (such as the mass of the W boson), the opening of new research areas (such as precision measurement of the top-quark mass and its properties), and searches for new physics in all of its forms. As shown in Figure 2, progress in each of these categories was obtained steadily throughout the whole running period of the Tevatron, as more and more data were accumulated.

The observation of Bs mixing is an example where ~ 0.1 fb–1 of 1990’s data were simply not enough to yield a statistically significant measurement. With 10 times more data by 2006, this phenomena was clearly established, with a statistical significance exceeding five standard deviations. As a result, many models of new physics that predicted an oscillation frequency away from its Standard Model expectation were excluded.

With about 2 fb–1 of data, enough events were accumulated to firmly establish a new family of heavy baryons containing a b quark, such as Cascade b and Sigma b baryons. Some of these discoveries had ~ 10–20 signal events, and a large number of proton–antiproton collisions, in addition to the development of new analysis methods, were critical for discovering these new baryons. It took a bit longer to discover the Omega b baryon, which is heavier and has a smaller production cross-section, but with 4 fb–1, 16 events were observed with backgrounds small enough to firmly establish its existence. It was exciting to witness how events accumulated in the corresponding mass peak with each additional inverse femtobarn of data collected.

It was not only discoveries that benefited from more data, high-precision measurements did also. The masses of elementary particles, such as the W boson, are among the most fundamental parameters in particle physics. With 1 fb–1 of data, samples containing hundreds of thousands of W bosons became available, resulting in an uncertainty of ~ 40 MeV or 0.05%. With 4 fb–1 of data, the accuracy of the measurement for each individual experiment was of ~ 20 MeV. With more data, many of the systematic uncertainties were successfully reduced as well. Ultimately, not all systematic uncertainties are better constrained by more data, and those become the limiting factor in the measurement.

Searches for physics beyond the Standard Model are always of the highest priority in the research programme of every energy-frontier collider, and the Tevatron was no exception. The number of publications in this area is the largest among all physics topics studied. Tighter and tighter limits have been set on many exotic theories and models, including supersymmetry. In many cases, limits on the masses of the new sought-after particles reached 1 TeV and above, about half of the Tevatron’s centre-of-mass energy.

The observation of the electroweak production of the top quark was among the many important tests of the Standard Model performed at the Tevatron. While the cross-section for electroweak single top-quark production is only a factor of two lower than top-quark pair production at the Tevatron, the final state with such a single decaying heavy particle was very difficult to detect in the presence of large backgrounds, such as W+jets production. It was the search for the single top quark where new multivariate analysis methods were very effectively used for the first time in the discovery of a new process, replacing standard “cut based” analyses and increasing the sensitivity of the search substantially. Even with these new analysis methods, 1 fb–1 of data was needed to obtain the first evidence for this process, and more than 2 fb–1 to make a firm discovery – almost 50 times more data than the amount of luminosity that was needed to discover the top-quark via pair production in 1995.

Image credit: Fermilab.

The analysis methods developed in the single top-quark observation were, in turn, very useful later on in the search for the Standard Model Higgs boson. The cross-sections for Higgs production are rather low at the Tevatron, so only the most probable decay modes to a pair of b quarks or W bosons contributed significantly to the search sensitivity. With 5 fb–1 of data accumulated, each experiment began to be sensitive to detecting Higgs bosons with mass around 165 GeV, where the Higgs decays mainly to a pair of W bosons. It became evident at that time that the statistical accuracy that each experiment could achieve on its own would not be enough to reach a strong result in their Higgs searches, so the two experiments combined their results to effectively double the luminosity. In this way, by 2011, the Tevatron experiments were able to exclude the Higgs boson in nearly the complete mass range allowed by the Standard Model. In the summer of 2012, using their full data set, the Tevatron’s experiments obtained evidence for Higgs boson production and its decay to a pair of b quarks, as the LHC experiments discovered the Higgs boson in its decays to bosons.

Lessons learnt

Among the many lessons learnt from the 25 year-long Tevatron run is that important results will appear steadily as the size of the data set increases. Among the reasons for this are the vast sets of studies that these general-purpose experiments perform. Hundreds of studies, for example, with the top quark or with particles containing a b quark or with processes containing a Higgs boson, provided exciting results at various luminosities when enough data for the next important result in one of the analyses were accumulated. Upgrades to the detectors are critical to handle ever-higher luminosities. Both CDF and D0 had major upgrades to the trackers, calorimeters and muon detectors, as well as trigger and data-acquisition systems. Developments of new analysis methods are also important, enabling the extraction of more information from the data. Improvements in the Tevatron luminosity were critical in keeping the luminosity doubling time to about a year or two, until the end of the programme, providing significant data increases over a relatively short period of time.

The impact of the Tevatron programme extended well beyond its originally planned physics goals, to a large extent due to the hundred-fold increase in the delivered luminosity with respect to what was originally planned. In many ways, even at a fixed energy, hadron colliders are a nearly inexhaustible source of physics. The LHC has gathered so far approximately 1% of its expected luminosity, a similar situation to where the Tevatron was back in 1995 at the time of the top-quark discovery. Based on the Tevatron experience, many more exciting results from the LHC experiments are yet to come.

• For further details, see www-d0.fnal.gov/d0_publications/d0_pubs_list_bydate.htmland www-cdf.fnal.gov/physics/physics.html.