Résumé

NA62 : l’usine à kaons du CERN

Le CERN est fort d’une longue tradition en physique des kaons, tradition perpétuée aujourd’hui par l’expérience NA62. La phase de mise en service a cédé la place en 2015 à la phase d’acquisition de données, qui devrait se poursuivre jusqu’en 2018. NA62 est conçue pour étudier avec précision la désintégration K+ → π+νν, mais elle est aussi utile pour examiner d’autres aspects, notamment l’universalité des leptons et les désintégrations radiatives. La qualité du détecteur, la possibilité d’utiliser des faisceaux secondaires aussi bien chargés que neutres, et la disponibilité prévue des faisceaux extraits du SPS pour la durée de l’exploitation du LHC font de NA62 une véritable usine à kaons.

Image credit: CERN.

CERN’s long tradition in kaon physics started in the 1960s with experiments at the Proton Synchrotron conducted by, among others, Jack Steinberger and Carlo Rubbia. It continued with NA31, CPLEAR, NA48 and its follow-ups. Next in line and currently active is NA62 – the high-intensity facility designed to study rare kaon decays, in particular those where the mother particle decays into a pion and two neutrinos. The nominal performance of the detector in terms of data quality and quantity is so good that the experiment can undeniably play the role of a kaon factory.

Using its unique set-up, NA62 will address with sufficient statistics and precision a basic question: does the Standard Model also work in the most suppressed corner of flavour-changing neutral currents (FCNCs)? According to theory, these processes are suppressed by the unitarity of the quark-mixing Cabibbo–Kobayashi–Maskawa matrix and by the Glashow–Iliopoulos–Maiani mechanism. What makes the kaons special is that some of these FCNCs are not affected by large hadronic matrix-element uncertainties because they can be normalised to a semi-leptonic mode described by the same form factor, which therefore drops out in the ratio. The poster child of these reactions is the K → πνν. By measuring the decay rate, it will be possible to determine a combination of Cabibbo–Kobayashi–Maskawa matrix elements independently of B decays. Discrepancies compared with expectations might be a signature of new physics.

Image credit: Augusto Ceccucci.

Testing Standard Model theoretical predictions is not easy, because the decay under study is predicted to occur with a probability of less than one part in 10 billion. Therefore, the first experimental challenge is to collect a sufficient number of kaon decays. To do so, in 2012, an intense secondary beam from the Super Proton Synchrotron (SPS), called K12, had to be completely rebuilt. Today, NA62 is exploiting this intense secondary beam, which has an instantaneous rate approaching 1 GHz. Although we know that approximately only 6% of the beam particles are kaons, each single particle sent by the SPS accelerator has to be identified before entering the experiment’s decay region. At the heart of the tracking system is the gigatracker (GTK), which is able to measure the impact position of the incoming particle and its arrival time. This information is used to associate the incoming particle with the event observed downstream, and to reconstruct its kinematics. To do so with the required sensitivity, 200 picoseconds time-resolution in the gigatracker is required.

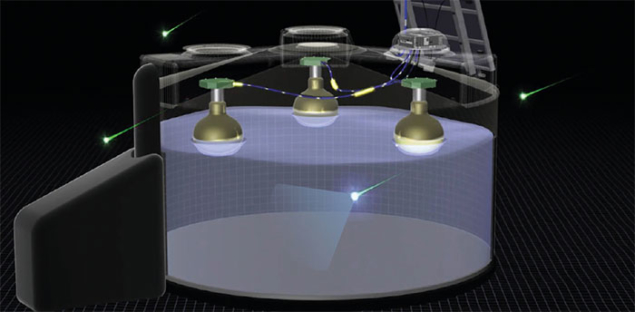

The GTK consists of a matrix of 200 columns by 90 rows of hybrid silicon pixels. To affect the trajectory of the particles as little as possible, the sensors are 200 μm thick and the pixel chip is 100 μm thick. The GTK is placed in a vacuum and operated at a temperature of –20 °C to reduce radiation-induced performance degradation. The NA62 collaboration has developed innovative ways to ensure effective cooling, using light materials to minimise their effect on particle trajectory.

Image credit: NA62 Collaboration.

In addition to measuring the direction and the momentum of each particle, the identity of the particle needs to be determined before it enters the decay tank. This is done using a differential Cherenkov counter (CEDAR) equipped with state-of-the-art optics and electronics to cope with the large particle rate.

Final-pion identification

There is a continuous struggle between particle physicists, who want to keep the amount of material in the tracking detectors to a minimum, and engineers, who need to ensure safety and prevent the explosion of pressurised devices operated inside the vacuum tank, such as the NA62 straw tracker made of more than 7000 thin tubes. In addition, the beam specialists would even prefer to have no detector at all. Any amount of material in the beam leads to scattering of particles into the detectors placed downstream, leading to potential backgrounds and unwanted additional counting rates. In NA62, the accepted signal is a single pion π+ and nothing else, so every trick in the book of experimental particle physics is used to determine the identity of the final pion, including a ring imaging Cherenkov (RICH) counter for pion/muon separation up to about 40 GeV/c.

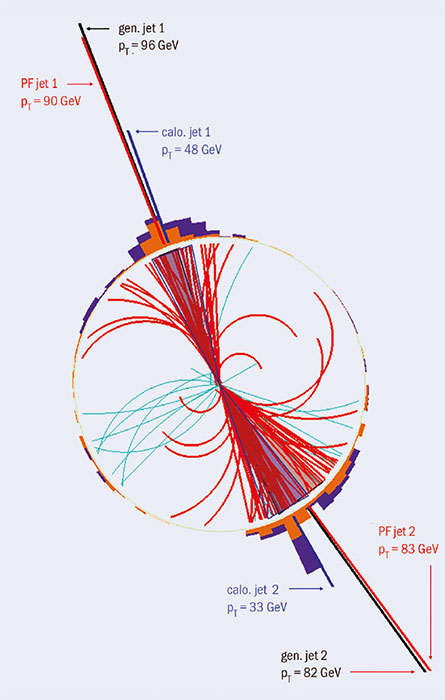

Perhaps the most striking feature of NA62 is the complex of electromagnetic calorimeters deployed along and downstream of the vacuum tank: 12 stations of lead-glass rings (using crystals refurbished from the OPAL barrel at LEP), of which 11 operate inside the vacuum tank; a liquid-krypton calorimeter, a legacy of NA48 but upgraded with new electronics, and smaller detectors complementing the acceptance. These calorimeters form the NA62 army deployed to suppress the background originating from K+ → π+π0 decays when both photons from the π0 decay are lost: only one π0 out of 107 remains undetected. As you have probably realised by now, NA62 is not a small experiment; a picture of the detector is shown in figure 1.

Image credit: NA62 Collaboration.

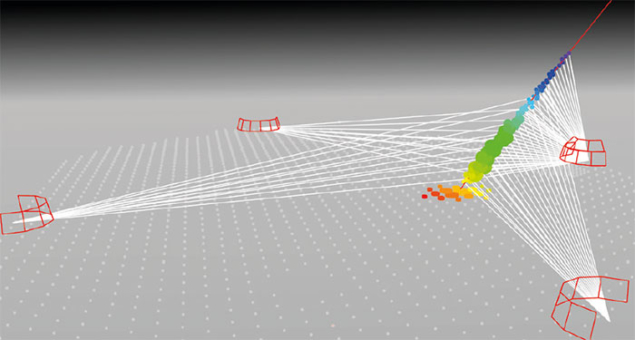

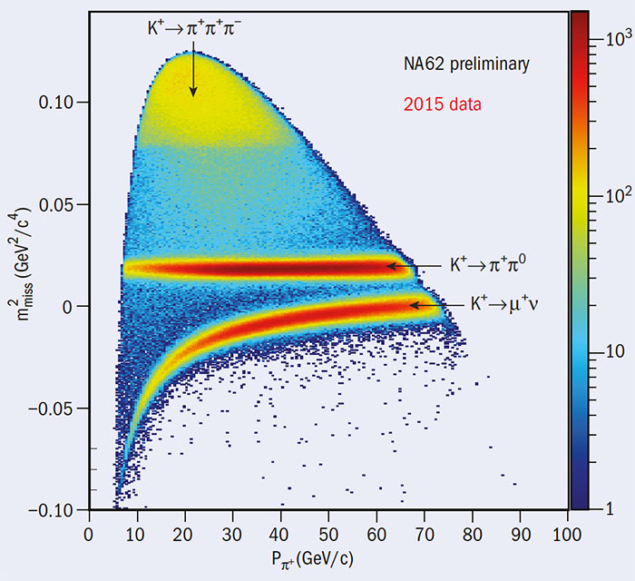

Even with a 65 m-long fiducial region, only 10% of the kaons decay usefully, so only six in 1000 of the incoming particles measured by the GTK actually end up being used to study kaon decays in NA62 – a big upfront price to pay. On the positive side, the advantage is the possibility to have full control of the initial and final states because the particles don’t cross any material apart from the trackers, and the kinematics of the decays can be reconstructed with great precision. To demonstrate the quality of the NA62 data, figure 3 shows events selected with a single track for incoming particles tagged as kaons and figure 4 shows the particle-identification capability.

In addition to suppressing the π0, NA62 has to suppress the background from muons. Most of the single rate in the large detectors is due to these particles, either from the more frequent pion and kaon decay (π+ → μ+ν and K+ → μ+ν) or originating from the dump of the primary proton beam. In addition to the already mentioned RICH, NA62 is equipped with hadron calorimeters and a fast muon detector at the end of the hall to deal with the muons. A powerful and innovative trigger-and-data-acquisition system is a crucial ingredient for the success of NA62, together with the commitment and dedication of each collaborator (see figure 2).

NA62 was commissioned in 2014 and 2015, and it is now in the middle of a first long phase of data-taking, which should last until the accelerator’s Long Shutdown 2 in 2018. The data collected so far indicate a detector performance in line with expectations, and preliminary results based on these data were shown at the Rencontres de Moriond Electroweak conference in La Thuile, Italy, in March. A big effort was invested to build this new experiment, and the collaboration is eager to exploit its physics potential to the full.

Having designed NA62 to address with precision the K+ → π+νν decay means that several other physics opportunities can be studied with the same detector. They range from the study of lepton universality to radiative decays. The improved apparatus with respect to NA48 should also allow measurements of π π scattering and semi-leptonic decays to be improved on, and possible low-mass long-lived particles to be looked for.

The quality of the detector, the possibility to use both charged and neutral secondary beams, and the foreseen availability of the SPS extracted beams for the duration of exploitation of the LHC make NA62 a bona-fide kaon factory.