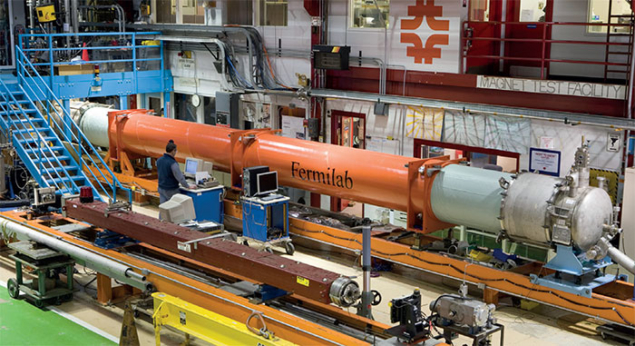

Image credit: Fermilab.

Driven by technology, scale, geopolitical reform, and even surprising discoveries, the field of particle physics is changing dramatically. This evolution is welcomed by some and decried by others, but ultimately is crucial for the survival of the field. The next 50 years of particle physics will be shaped not only by the number, character and partnerships of labs around the world and their ability to deliver exciting science, but also by their capacity to innovate.

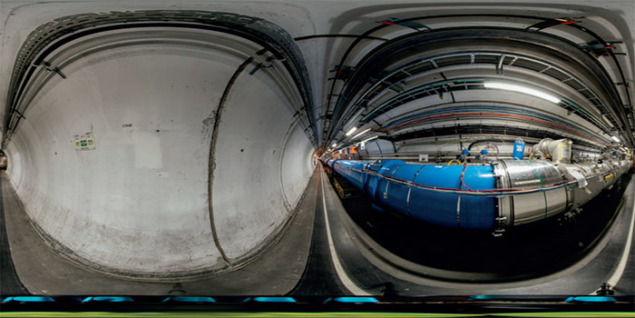

Increasingly, the science we wish to pursue as a field has demanded large, even mega-facilities. CERN’s LHC is the largest, but the International Linear Collider (ILC) project and plans for a large circular collider in China are not far behind, and could even be new mega-science facilities. The main centres of particle physics around the world have changed significantly in the last several decades due to this trend. But a new picture is emerging, one where co-ordination among and participation in these mega-efforts is required at an international level. A more co-ordinated global playing field is developing, but “in transition” would best describe the situation at present.

Europe and North America have clear directions of travel. CERN has emerged as the leader of particle physics in Europe; the US has only Fermilab devoted entirely to particle physics. Other national labs in the US and Europe have diversified into other areas of science and some have found a niche for particle physics while also connecting strongly to the research programmes at Fermilab and CERN. Indeed, in the US a network of laboratories has emerged involving SLAC, Brookhaven, Argonne and Berkeley. Once quite separate, now these labs contribute to the LHC and to the neutrino programme based at Fermilab. Furthermore, each lab is becoming specialised in certain science and technology areas, while their collective talents are being developed and protected by the Department of Energy. As a result, CERN and Fermilab are stronger partners than ever before. Likewise, several European labs are now engaged or planning to engage in the ambitious neutrino programme being hosted by Fermilab, for which CERN continues to be the largest partner.

Will this trend continue, with laboratories worldwide functioning more like a network, or will competition slow down the inevitable end game? There are at least a couple of wild cards in the deck at the moment. Chief issues for the future are how aggressively and at what scale will China enter the field with its Circular Electron Positron Collider and Super Proton–Proton Collider projects, and whether Japan will move forward to build the ILC. The two projects have obvious science overlap and some differences, and if either project moves forward, Europe and the US will want to be involved and the impact could be large.

The global political environment is also fast evolving, and science is not immune from fiscal cuts or other changes taking place. While it is difficult to predict the future, fiscal austerity is here to stay for the near term. The consequences may be dramatic or could continue the trend of the last few decades, shrinking and consolidating our field. Rising above this trend will take focus, co-ordination and hard work. More importantly than ever, the worldwide community needs to demonstrate the value of basic science to funding stakeholders and the public, and to propose compelling reasons why the pursuit of particle physics deserves its share of funding.

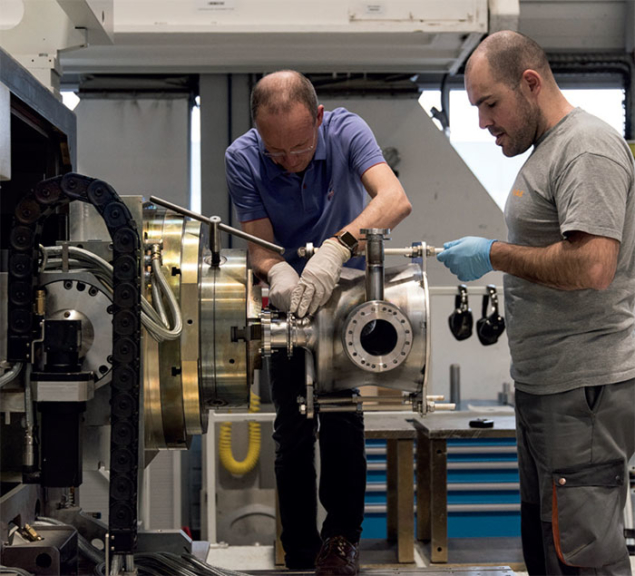

Top-quality, world-leading science should be the primary theme, but it is not enough. The importance of social and economic impact will loom ever larger, and the usual rhetoric about it taking 40 years to reap the benefits from basic research – even if true – will no longer suffice. Innovation, more specifically the role of science in fuelling economic growth, is the favourite word of many governments around the world. Particle physics needs to be engaged in this discussion and contribute its talent. Is this a laboratory effort, a network of laboratories effort, or a global effort? For the moment, innovation is local, sometimes national, but our field is used to thinking even bigger. The opportunity to lead in globalisation is on our doorstep once again.