If you live in a low- or middle-income country (LMIC), your chances of surviving cancer are significantly lower than if you live in a wealthier economy. That’s largely due to the availability of radiation therapy (see “The changing landscape of cancer therapy”). Between 2015 and 2035, the number of cancer diagnoses worldwide is expected to increase by 10 million, with around 65% of those cases in poorer economies. Approximately 12,600 new radiotherapy treatment machines and up to 130,000 trained oncologists, medical physicists and technicians will be needed to treat those patients.

Experts in accelerator design, medical physics and oncology met at CERN on 26–27 October 2017 to address the technical challenge of designing a robust linear accelerator (linac) for use in more challenging environments. Jointly organised by CERN, the International Cancer Expert Corps (ICEC) and the UK Science and Technology Facilities Council (STFC), the workshop was funded through the UK Global Challenges Research Fund, enabling participants from Botswana, Ghana, Jordan, Nigeria and Tanzania to share their local knowledge and perspectives. The event followed a successful inaugural workshop in November 2016, also held at CERN (CERN Courier March 2017 p31).

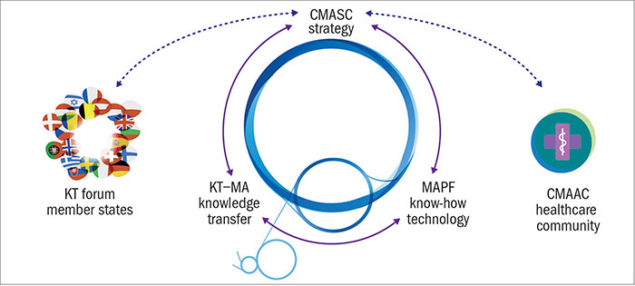

The goal is to develop a medical linear accelerator that provides state-of-the-art radiation therapy in situations where the power supply is unreliable, the climate harsh and/or communications poor. The immediate objective is to develop work plans involving Official Development Assistance (ODA) countries that link to the following technical areas (which correspond to technical sessions in the October workshop): RF power systems; durable and sustainable power supplies; beam production and control; safety and operability; and computing.

Participants agreed that improving the operation and reliability of selected components of medical linear accelerators is essential to deliver better linear accelerator and associated instrumentation in the next three to seven years. A frequent impediment to reliable delivery of radiotherapy in LMICs, and other underserved regions of the world, is the environment within which the sophisticated linear accelerator must function. Excessive ambient temperatures, inadequate cooling of machines and buildings, extensive dust in the dry season and the high humidity in some ODA countries are only a few of the environmental factors that can challenge both the robustness of treatment machines and the general infrastructure.

Image credits: (left and right) H Makwani, (middle) S Chinedu.

Simplicity of operation is another significant factor in using linear accelerators in clinics. Limiting factors to the development of radiotherapy in lower-resourced nations don’t just include the cost of equipment and infrastructure, but also a shortage of trained personnel to properly calibrate and maintain the equipment and to deliver high-quality treatment. On one hand, the radiation technologist should be able to set treatments up under the direction of the radiation oncologist and in accordance with the treatment plan. On the other hand, maintenance of the linear accelerators should also be as easy as possible – from remote upgrades and monitoring to anticipate failure of components. These centres, and their machines, should be able to provide treatment on a 24/7 basis if needed, and, at the same time, deliver exclusive first-class treatment consistent with that offered in richer countries. STFC will help to transform ideas and projects presented in the next workshop, scheduled for March 2018, into a comprehensive technology proposal for a novel linear accelerator. This will then be submitted to the Global Challenges Research Fund Foundation Awards 2018 call for further funding. This ambitious project aims to have facilities and staff available to treat patients in low- and middle-income countries within 10 years.