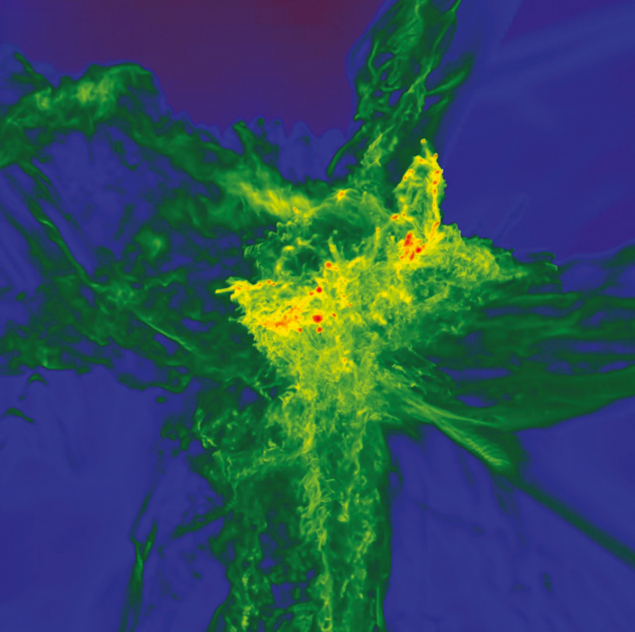

Cosmology has long predicted that the first generation of stars should differ strongly from those forming today. Born out of pristine gas of only hydrogen and helium, they could have reached masses between a thousand and ten thousand times that of the Sun, before collapsing after only a few million years. Such “primordial monsters” have been proposed as the seeds of the first quasars (see “Collapsing monster” image), but clear observations had until now been lacking.

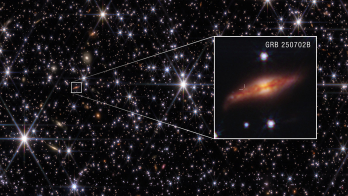

An analysis of the galaxy GS 3073 using the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) now carries an unexpectedly loud message from the first generation of stars: there is far too much nitrogen to be explained by known stellar populations. This mismatch suggests a different kind of stellar ancestor, one no longer present in our universe. It is the first indirect evidence for the long-sought primordial monsters, first proposed in the early 1960s by Fred Hoyle and William Fowler in the US, and independently by Yakov Zel’dovich and Igor Novikov in the Soviet Union, in attempts to explain the newly discovered quasars.

Black-hole powered

JWST’s near-infrared spectroscopy of GS 3073 reveals the highest nitrogen-to-oxygen ratio yet measured while surveying the universe’s first billion years. Its dense central gas contains almost as many nitrogen atoms as oxygen, while carbon and neon are comparatively modest. In addition, the galaxy has an active nucleus powered by a black hole that is already millions to hundreds of millions of times the mass of the Sun, despite the galaxy’s low metallicity.

Could a primordial monster explain GS 3073? The answer lies in how these huge stars mix and burn their fuel.

GS 3073 could offer the first chemical evidence for the largest stars the universe ever formed and to the early production of massive black holes

Simulations reveal that after an initial phase of hydrogen burning in the core, these stars ignite helium, producing large amounts of carbon and oxygen. Because the stars are so luminous and extended, their interiors are strongly convective. Hot material rises, cool material sinks and chemical elements are constantly stirred. Freshly made carbon from the helium-burning core leaks outward into a surrounding shell where hydrogen is still burning. There, a sequence of reactions known as the CNO cycle converts hydrogen into helium while steadily turning carbon into nitrogen. Over time, this process loads the outer parts of the star with nitrogen, while also moderately enhancing oxygen and neon. The heaviest elements produced in the final burning stages remain trapped in the core and never reach the surface before the star collapses.

Mass loss from such primordial stars is uncertain. Without metals, they cannot generate the strong line-driven winds familiar from massive stars today. Instead, mass may be lost through pulsations, eruptions or interactions in dense environments. But simulations allow a robust conclusion: supermassive primordial stars between roughly one thousand and ten thousand solar masses naturally produce gas with nitrogen-to-oxygen, carbon-to-oxygen and neon-to-oxygen ratios that match those measured in the dense regions of GS 3073. Stars significantly lighter or heavier than this range cannot reproduce the extreme nitrogen-to-oxygen ratio, even before carbon and neon are taken into account.

Under pressure

Radiation pressure could have supported these primordial monsters for no more than a few million years. As their cores contract and heat, photons become energetic enough to convert into electron–positron pairs, reducing the radiation pressure. For classical massive stars with masses in the range of nine to 120 times the mass of the sun, this instability leads to a thermonuclear explosion that we refer to as a supernova. By contrast, supermassive stars are so dominated by gravity due to their much larger mass that they collapse directly into black holes, without undergoing a supernova explosion.

This provides a natural path from supermassive primordial stars to the over-massive black hole now seen in GS 3073’s nucleus. In this scenario, one or a few such giants enrich the surrounding gas with nitrogen-rich material through mass loss during their lives, and leave behind black-hole seeds that later grow by accretion. If this picture is correct, GS 3073 offers the first chemical evidence for the largest stars the universe ever formed and ties them directly to the early production of massive black holes. Future JWST observations, together with next-generation ground-based telescopes, will search for more nitrogen-loud galaxies and map their chemical structures in greater detail.

Further reading

D Nandal et al. 2025 ApJL 994 L11.