What is the fate of the universe? Why is there more matter than antimatter? What lurks beyond the Standard Model? Valentina Cairo and Steven Lowette explore the physics reach of the High-Luminosity LHC.

The Higgs boson is uniquely simple – the only Standard Model particle with no spin. Paradoxically, this allows its behaviour to be uniquely complex, notably due to the “scalar potential” built from the strength of its own field. Shaped like a Mexican hat, the Higgs potential has a local maximum of potential energy at zero field, and a ring of minima surrounding it.

In the past, the Higgs field settled into this ring, where it still dwells today. Since then, the field has been permanently “switched on” – a directionless field with a nonzero “vacuum expectation value” that is ubiquitous throughout the universe. Its interactions with a number of other fundamental particles give them mass. What remains unclear is how the Higgs field behaves once pushed from this familiar minimum. Where will it go next, how did it get there in the first place and might new physics modify this picture?

The LHC alone has shed experimental light on this physics. Further progress on this compelling frontier of fundamental science requires upgrades and new colliders. The next step along this path is the High-Luminosity LHC (HL-LHC), which is scheduled to begin operations in 2030. The HL-LHC is set to outperform the LHC by far, with a total dataset of 380 million Higgs bosons created inside the ATLAS and CMS experiments – a sample more than 10 times larger than any studied so far (see “A leap in technology” panel). We still need to unlock the full reach of the HL-LHC, but three scientific questions may serve to illustrate what can be studied with 380 million Higgs bosons.

What is the fate of the universe?

The stability of our universe hangs in a delicate balance. Quantum corrections could make the Higgs potential bend downward again at high values of the Higgs field, creating a lower-energy state beneath our own (see “The Higgs potential” panel). Through quantum tunnelling, tiny regions of space could spontaneously make the transition, releasing energy as the Higgs field settles into a new minimum of the Higgs potential. Bubbles of the new vacuum would expand at the speed of light, changing the vacuum state of the regions they encounter.

Details matter. The Higgs potential is modified by the effect of virtual loops from all particles interacting with the Higgs field. Bosons push the Higgs potential upwards at high field values, and fermions pull it downwards. If the Standard Model remains valid up to high field values, perhaps as high as the Planck scale where quantum gravity is expected to become relevant, these corrections may determine the ultimate fate of the vacuum. As the most massive Standard Model particle yet discovered, the top quark makes a dominant negative contribution at high energies and field strengths. Together with a smaller effect from the mass of the Higgs boson itself, the top-quark mass defines three possible regimes.

In the stable case, the Higgs potential remains above the current minimum up to high field values, and no deeper minimum is present.

If a second, lower minimum forms at high field values, but is shielded by a large energy barrier, the vacuum can be “metastable”. In that case, quantum tunnelling could in principle occur, but on timescales exceeding the age of the universe.

In the unstable regime, the barrier is low enough for decay to have already occurred.

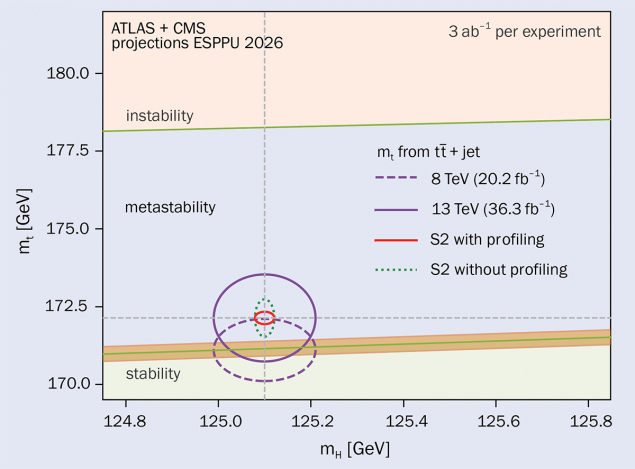

Current observations place our universe safely within the metastable zone, far from any immediate change (see “A second minimum?” figure). Yet the precision of the latest LHC measurements, based on independent determinations of the top-quark mass (purple ellipses), leaves unresolved whether the universe is stable or metastable. Other uncertainties, such as that on the strength of nature’s strong coupling, also affect the distinction between the two regimes, shifting the boundary between stability and metastability (orange band).

The HL-LHC will be well placed to help resolve the question of the stability of the vacuum thanks to improvements in the measurements of the top quark and Higgs-boson masses (red ellipse). This will rely on combining the HL-LHC’s large dataset, the ingenuity of expected analysis improvements and theoretical progress in the fundamental interpretation of these measurements.

The Higgs potential

The Higgs boson is the only Standard Model particle with no spin – a quantum number that behaves as if fundamental particles were spinning, but which cannot correspond to a physical rotation without violating relativity theory.

This allows the Higgs field to experience a scalar potential – energy penalties that depend on the strength of the Higgs field itself. This is forbidden for fermions

(spin ½) and massless bosons (spin 1) by Lorentz symmetry and gauge invariance.

In the Standard Model, the Higgs field is subject to the Higgs potential, shaped like a Mexican hat, with a maximum of potential energy at zero field, and a minimum at a ring in the complex plane of values of the Higgs field. Its polynomial form is restricted by gauge symmetry. Experimentally, it can be inferred by measuring properties of the Higgs boson such as its self-coupling λ3.

Two effects then modify the Mexican-hat shape in ways that are difficult to predict but have important consequences for particle physics and cosmology. These are due to the interactions of the Higgs field with virtual particles and real thermal excitations. Quantum fluctuations modify the energy penalty of exciting the Higgs field due to virtual loops from all Standard Model particles. Changes in the temperature of the universe also generate changes in the shape of the Higgs potential due to the interaction of the Higgs field with real thermal excitations in the hot early universe. Properties such as λ3 are also affected by these effects.

Davide De Biasio associate editor

Why is there more matter than antimatter?

The Higgs potential wasn’t always a Mexican hat. If the early universe got hot enough, interactions between the Higgs field and a hot plasma of particles shaped the Higgs potential into a steep bowl with a minimum at zero field, yielding no vacuum expectation value. As the universe cooled, this potential drooped into its familiar Mexican-hat shape, with a central peak surrounded by a ring of minima, where the Higgs field sits today. But did the Higgs field pass through an intermediate stage, with a “bump” separating the inner minimum from the ring?

The answer depends on the strength of the Higgs self-coupling, λ3, which governs the trilinear coupling where three Higgs-boson lines meet at a single vertex in a Feynman diagram. But λ3 is not yet measured. The most recent joint ATLAS and CMS analysis excludes values outside of –0.71 to 6.1 times its expected value in the Standard Model with 95% confidence.

In the Standard Model, the vacuum smoothly rolled from zero Higgs field to its new minimum in the outer ring. But if λ3 were at least 50% stronger than in the Standard Model, this smooth “crossover” phase transition may have been prevented by an intermediate bump. The vacuum would then have experienced a strong first-order phase transition (FOPT), like ice melting or water boiling at everyday pressures. As the universe cooled, regions of space would have tunnelled into the new vacuum, forming bubbles that expanded and merged. These bubble-wall collisions, combined with additional processes beyond the Standard Model that violate the conservation of both charge and parity together, could have contributed to the observed excess of matter over antimatter – one of the deepest mysteries of modern physics, wherein there appears to have been an excess of baryons over antibaryons in the early universe of roughly one part in a billion, resulting in the surplus we observe today after the annihilation of the others into photons.

The most direct probe of λ3 comes from Higgs-boson pair production (HH). HH production happens most often by the fusion of gluons from the colliding protons to create a top-quark loop that emits either two Higgs bosons or one Higgs boson splitting into two, yielding sensitivity to λ3.

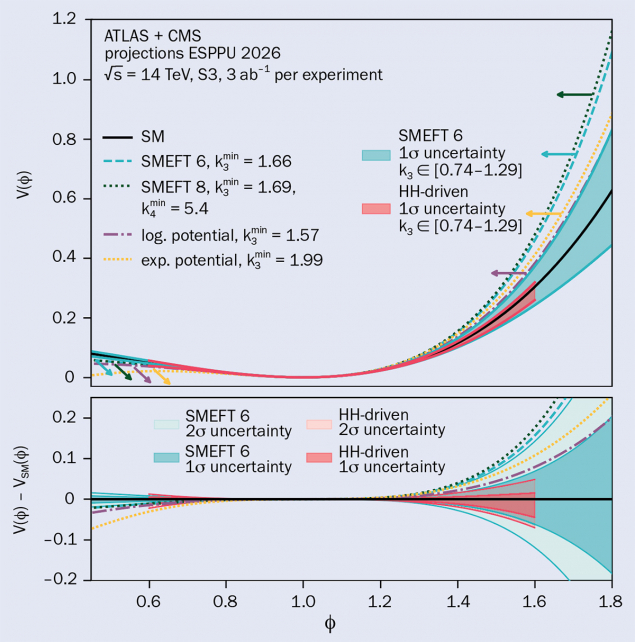

HH production happens only once for every thousand Higgs bosons produced in the LHC. Searches for this process are already underway, with analyses of the Run 2 dataset by the ATLAS and CMS collaborations showing that a signal 2.5 times larger than the Standard Model expectation is already excluded. This progress far exceeds early expectations, suggesting that the HL-LHC may finally bring λ3 within experimental reach, clarifying the shape of the Higgs potential near its current minimum (see “Constraining the Higgs potential” figure).

Measuring λ3 at the HL-LHC would shed light on whether the Higgs potential follows the Standard Model prediction (black line) or alternative shapes (dashed lines), which may arise from physics beyond the Standard Model (BSM). The corresponding sensitivity can be illustrated through two complementary approaches: one based on HH production, assuming no effects beyond λ3 and providing a largely model-independent view near the potential’s minimum (red bands); and an approach that incorporates higher-order effects, which extend the reach over a broader range of the Higgs field (blue bands).

Since the previous update of the European Strategy for Particle Physics, the projected sensitivity has vastly improved. The combined ATLAS and CMS results are now expected to yield a discovery significance exceeding 7σ, should HH production occur at the Standard Model rate. By the end of the HL-LHC programme, the two experiments are expected to determine λ3 with a 1σ uncertainty of about 30% – enough to exclude the considered BSM potentials at the 95% confidence level if the self-coupling matches the Standard Model prediction.

What lurks beyond the Standard Model?

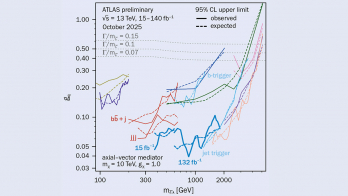

Puzzles such as the origin of dark matter and the nature of neutrino masses suggest that new physics must lie beyond the Standard Model. With greatly expanded data sets at the HL-LHC, new phenomena may become detectable as resonant peaks from undiscovered particles or deviations in precision observables.

As an example, consider a BSM scenario that includes an additional scalar boson “S” that mixes with the Higgs boson but remains blind to other Standard Model fields (see “Spotting a new scalar” figure). S could induce observable differences in λ3 (horizontal axis) and the coupling of the Higgs boson to the Z boson, gHZZ (vertical axis). Both couplings are plotted as a factor of their expected Standard Model values. The figure explores scenarios where the coupling deviates from its Standard Model value by as little as a tenth of a permille, and where the trilinear self-coupling may be between 0.5 and 2.5 times the value. Such models could prove to be the underlying cause of deviations from the Standard Model such as contributing to the matter–antimatter asymmetry in the universe. Combinations of model parameters that could allow for a strong FOPT in the early universe are plotted as black dots.

This example analysis serves to illustrate the complementarity of precision measurements and direct searches at the HL-LHC. The parameter space can be narrowed by measuring the axis variables λ3 and gHZZ (blue and orange bands). Direct searches for S → HH and S → ZZ will be able to probe or exclude many of the remaining models (red and purple regions), leaving room for scenarios in which new physics is almost entirely decoupled from the Standard Model.

What’s next?

What once might have seemed like science fiction has become a milestone in our understanding of nature. When Ursula von der Leyen, president of the European Commission, last visited CERN, she reflected on recent progress in the field.

“When you designed a 27 km underground tunnel where particles would clash at almost the speed of light, many thought you were daydreaming. And when you started looking for the Higgs boson, the chances of success seemed incredibly low, but you always proved the sceptics wrong. Your story is one of progress against all odds.”

Today, at a pivotal moment for particle physics, we are redefining what we believe is possible. Plucked from the ATLAS and CMS collaborations’ inputs to the 2026 update to the European Strategy for Particle Physics (CERN Courier November/December 2025 p23), the analyses described in this article are just a snapshot of what will be possible at the HL-LHC. In close collaboration with the theory community, experimentalists will use the unmatched datasets and detector capabilities of the HL-LHC and allow the field to explore a rich landscape of anticipated phenomena, including many signatures yet to be imagined.

The future starts now, and it is for us to build.

A leap in technology

The HL-LHC will deliver proton–proton collisions at least five times more intensely than the LHC’s original design. By the end of its lifetime, the HL-LHC is expected to accumulate an integrated dataset of around 3 ab–1 of proton–proton collisions – about six times the data collected during the LHC era.

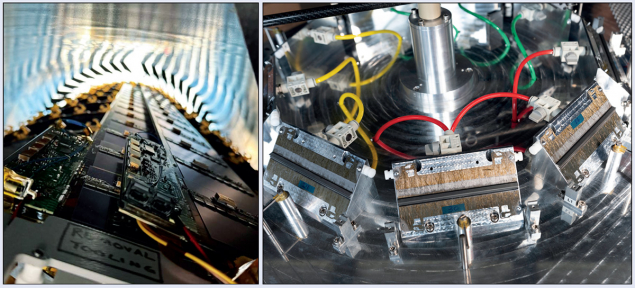

ATLAS and CMS are undergoing extensive upgrades to cope with the intense environment created by a “pileup” of up to 200 simultaneous proton–proton interactions per bunch crossing. For this, researchers are building ever more precise particle detectors and developing faster, more intelligent software.

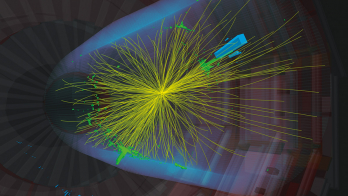

The ATLAS and CMS collaborations will implement a full upgrade of their tracking systems, providing extended detector coverage and improved spatial resolution (see “Tracking upgrades” figure). New capabilities are added to either or both experiments, such as precision timing layers outside the tracker, a more performant high-granularity forward calorimeter, new muon detectors designed to handle the increased particle flux, and modernised front- and back-end electronics across the calorimeter and muon systems, among other improvements.

Major advances are also being made in data readout, particle reconstruction and event selection. These include track reconstruction capabilities in the trigger and a significantly increased latency, allowing for more advanced decisions about which collisions to keep for offline analysis. Novel selection techniques are also emerging to handle very high event rates with minimal event content, along with AI-assisted methods for identifying anomalous events already in the first stages of the trigger chain.

Finally, detector advancements go hand-in-hand with innovation in algorithms. The reconstruction of physics objects is being revolutionised by higher detector granularity, precise timing, and the integration of machine learning and hardware accelerators such as modern GPUs. These developments will significantly enhance the identification of charged-particle tracks, interaction vertices, b-quark-initiated jets, tau leptons and other signatures – far surpassing the capabilities foreseen when the HL-LHC was first conceived.

Further reading

ATLAS Collab. and CMS Collab. 2025 arXiv:2504.00672.

ATLAS Collab. 2025 ATLAS-CONF-2025-012.

CMS Collab. 2025 CMS-PAS-HIG-25-014.