Antonino Zichichi tells Bob Swarup about his initiative to bring frontier research in physics into the heart of Italian schools and to encourage the next generation of physicists.

In May 2004, a major webcast linked CERN and high schools all over Italy to inaugurate the Extreme Energy Events (EEE) Project. Launched on the occasion of the visit to CERN of the Italian Minister of Education, University and Research, the project is the initiative of Antonino Zichichi from Bologna University and CERN.

What is the main idea behind the project?

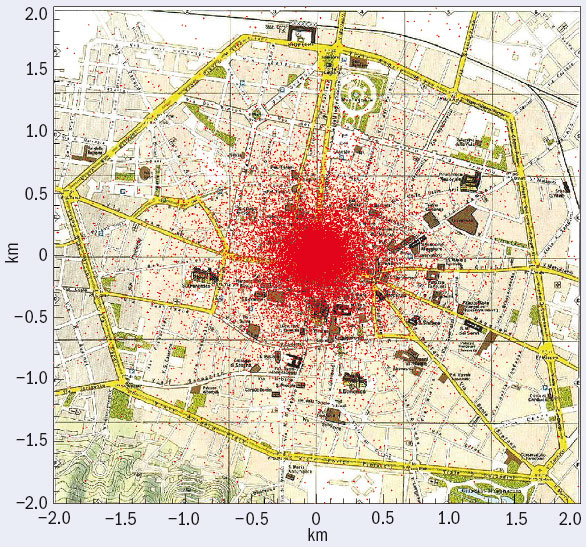

This project is meant to be the most extensive experiment to detect muon showers induced by extremely energetic primary cosmic rays (protons or nuclei) interacting in the atmosphere. Ultimately, it will cover a million square kilometres of Italian and Swiss territory. It would have been very expensive to implement such a large project without involving existing structures, namely schools all over Italy and part of Switzerland. This “economic” strategy also has the advantage of bringing advanced physics research to the heart of the new generation of students.

How will the experiment detect cosmic-ray showers?

The EEE telescopes, distributed over an immense area, will be tracking devices, capable of reconstructing the trajectories of the charged particles traversing them. These particles are the secondary cosmic rays produced in the showers, and are mostly muons at sea level. The project is based on a very advanced detector unit: the multigap resistive plate chamber (MRPC) (Cerron-Zeballos et al. 1996). An EEE telescope comprises three layers of MRPCs. We have developed these chambers for the ALICE time-of-flight detector at CERN’s LHC (Akindinov et al. 2004). Their performance in terms of detection efficiency and time resolution is outstanding.

However, the EEE Project also aims to bring science into high schools (Zichichi 2004). This is why the plan was for all of the MRPCs to be built by teams of school pupils supervised by their teachers at CERN or in the nearest laboratory (located in the closest university or research institute). After the MRPC construction phase, school pupils participate in the installation, testing and start-up of the EEE telescope in their school, then in its maintenance and data-acquisition, and later in the analysis of the data. Of course the scientific and technical staff of the universities and research institutes collaborating in the project coordinate and guide everything.

The telescopes will be coupled to GPS units and interconnected via a network. A dedicated PC will locally acquire the MRPC signals produced by each telescope and will then transfer them to the largest Italian computer centre in Bologna for analysis using Grid middleware.

How much does the project cost and how is it funded?

The cost is minimal because we install our detectors at existing structures (schools). The EEE Project was funded in 2005 by the Italian Ministry of Education, University and Research, and by Italian research institutes such as INFN and the Enrico Fermi Centre. The cost of an EEE unit (that is, a complete telescope, including PC, laboratory equipment, cables, gas system, etc.) is about €50,000. CERN, the World Federation of Scientists, the Italian National Research Council and many Italian universities are also participating in the project. Owing to the success of the project and to its undoubted impact on education and research potential, we expect more funding in the coming years.

What is the status of the project? How many schools are involved so far and what is the next step?

In one year, pupils from more than 20 high schools have built more than 70 MRPCs at CERN. Nine pilot sites are equipped with EEE telescopes: at CERN, at the INFN Gran Sasso Laboratory, at the INFN Frascati Laboratory and in the INFN sections in Bologna (central Italy), Cagliari (Sardinia, central-western Italy), Catania (Sicily, southern Italy), Lecce (south-east Italy) and Turin (north-west Italy). The remaining MRPCs are currently moving from Geneva to Italy for the other high schools that are involved so far. We foresee that all of these telescopes should soon be collecting data. Meanwhile the construction of other MRPCs at CERN continues, thanks to a new wave of pupils from other Italian high schools. More than 50 schools are already queuing up to be part of the EEE Project.

The next stage of the project is to continue expanding, increasing its coverage and involving as many high schools as possible in this frontier experimental research in fundamental physics.

What do you believe the project contributes to education?

The direct involvement of young pupils in the project is the most efficient way to contribute to their learning while doing advanced research in physics. The pupils will be personally involved in advanced research and will acquire a deeper knowledge of particle and astroparticle physics, experimental tools, data-acquisition systems, software, networks, etc. They will gain direct access to the data and to the working methods typical of modern research work.

How does EEE differ from schools projects in other countries?

When I started to speak about the project I knew of no other proposals. Now some educational cosmic-ray projects have been proposed in other countries. The detectors are groups of scintillation counters, typically on the school’s roof, and not in the building as with the EEE telescopes. These projects don’t use tracking devices.

What will the project contribute to research?

There are short- and long-range time coincidences between close (within the same city) and distant telescopes, and the tracking capabilities of the telescopes will determine with good precision the direction of the incoming primary cosmic ray. Therefore, the EEE Project can study not only large showers of muons originating from a common vertex, but also correlations between separated showers that might be produced by bundles of primaries. The project thus allows a large variety of studies, from measuring the local muon flux in a single telescope, to detecting extensive air showers producing time correlations in the same metropolitan area, to searching for large-scale correlations between showers detected in telescopes tens, hundreds or thousands of kilometres apart. When complete – that is, equipped with at least 100 telescopes – the EEE Project will compete strongly with other high-energy cosmic-ray experiments searching for extreme-energy extended air showers.

Further reading

A N Akindinov et al. 2004 Nucl. Inst. Meth. A533 74.

E Cerron-Zeballos et al. 1996 Nucl. Inst. Meth. A374 132.

A Zichichi 2005 Progetto “la Scienza nelle Scuole”, EEE – Extreme Energy Events, Società Italiana di Fisica.