Uncovering Quantum Field Theory and the Standard Model: From Fundamental Concepts to Dynamical Mechanisms, by Wolfgang Bietenholz and Uwe-Jens Wiese, Cambridge University Press

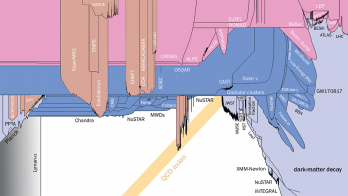

Quantum field theory unites quantum physics with special relativity. It is the framework of the Standard Model (SM), which describes the electromagnetic, weak and strong interactions as gauge forces, mediated by photons, gluons and W and Z bosons, plus additional interactions mediated by the Higgs field. The success of the SM has exceeded all expectations, and its mathematical structure has led to a number of impressive predictions. These include the existence of the charm quark, discovered in 1974, and the existence of the Higgs boson, discovered in 2012.

Uncovering Quantum Field Theory and the Standard Model by Wolfgang Bietenholz of the National Autonomous University of Mexico and Uwe-Jens Wiese from the University of Bern, explains the foundations of quantum field theory in great depth, from classical field theory and canonical quantisation to regularisation and renormalisation, via path integrals and the renormalisation group. What really makes the book special are frequently discussed relations to statistical mechanics and condensed-matter physics.

Riding a wave

The section on particles and “wavicles” is highly original. In quantum field theory, quantised excitations of fields cannot be interpreted as point-like particles. Unlike massive particles in non-relativistic quantum mechanics, these excitations have non-trivial localisation properties, which apply to photons and electrons alike. To emphasise the difference between non-relativistic particles and wave excitations in a relativistic theory, one may refer to them as “wavicles”, following Frank Wilczek. As discussed in chapter 3, an intuitive understanding of wavicles can be gained by the analogy to phonons in a crystal. Another remarkable feature of charged fields is the infinite extension of their excitations due to their Coulomb field. This means that any charged state necessarily includes an infrared cloud of soft gauge bosons. As a result, they cannot be described by ordinary one-particle states and are referred to as “infraparticles”. Their properties, along with the related “superselection sectors,” are explained in the section on scalar quantum electrodynamics.

The SM can be characterised as a non-abelian chiral gauge theory. Bietenholz and Wiese explain the various aspects of chirality in great detail. Anomalies in global and local symmetries are carefully discussed in the continuum as well as on a space–time lattice, based on the Ginsparg–Wilson relation and Lüscher’s lattice chiral symmetry. Confinement of quarks and gluons, the hadron spectrum, the parton model and hard processes, chiral perturbation theory and deconfinement at high temperatures uncover perturbative and non-perturbative aspects of quantum chromodynamics (QCD), the theory of strong interactions. Numerical simulations of strongly coupled lattice Yang–Mills theories are very demanding. During the past four decades, much progress has been made in turning lattice QCD into a quantitative reliable tool by controlling statistical and systematic uncertainties, which is clearly explained to the critical reader. The treatment of QCD is supplemented by an introduction to the electroweak theory covering the Higgs mechanism, electroweak symmetry breaking and flavour physics of quarks and leptons.

The number of quark colours, which is three in nature, plays a prominent role in this book. At the quantum level, gauge symmetries can fail due to anomalies, rendering a theory inconsistent. The SM is free of anomalies, but this only works because of a delicate interplay between quark and lepton charges and the number of colours. An important example of this interplay is the decay of the neutral pion into two photons. The subtleties of this process are explained in chapter 24.

The number of quark colours, which is three in nature, plays a prominent role in this book

Most remarkably, the SM predicts baryon-number-violating processes. This arises from the vacuum structure of the weak SU(2) gauge fields, which involves topologically distinct field configurations. Quantum tunnelling between them, together with the anomaly in the baryon–number current, leads to baryon–number violating transitions, as discussed in chapter 26. Similarly, in QCD a non-trivial topology of the gluon field leads to an explicit breaking of the flavour-singlet axial symmetry and, subsequently, to the mass of the η′ meson. Moreover, the gauge field topology gives rise to an additional parameter in QCD, the vacuum-angle θ. Since this parameter induces an electric dipole moment of the neutron that satisfies a strong upper bound, this confronts us with the strong-CP problem: what constrains θ to be so tiny that the experimental upper bound on the neutron dipole moment is satisfied? A solution may be provided by the Peccei–Quinn symmetry and axions, as discussed in a dedicated chapter.

By analogy with the QCD vacuum angle, one can introduce a CP-violating electromagnetic parameter θ into the SM – even though it has no physical effect in pure QED. This brings us to a gem of the book: its discussion of the Witten effect. In the presence of such a θ, the electric charge of a magnetic monopole becomes θ/2π plus an integer. This leads to the remarkable conclusion that for non-zero θ, all monopoles become dyons, carrying both electric and magnetic charge.

The SM is an effective low-energy theory and we do not know at what energy scale elements of a more fundamental theory will become visible. Its gauge structure and quark and lepton content hint at a possible unification of the interactions into a larger gauge group, which is discussed in the final chapter. Once gravity is included, one is confronted with a hierarchy problem: the question of why the electroweak scale is so small compared to the Planck mass, at which the Compton wavelength of a particle and its Schwarzschild radius coincide. Hence, at Planck energies quantum gravitational effects cannot be ignored. Perhaps, solving the electroweak hierarchy puzzle requires working with supersymmetric theories. For all students and scientists struggling with the SM and exploring possible extensions, the nine appendices will be a very valuable source of information for their research.