Marianne Johansen goes in search of facts about an emotive issue.

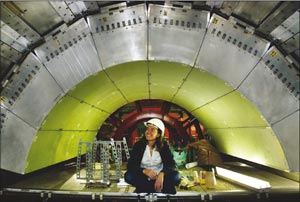

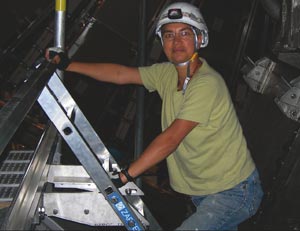

Physics has always had a relatively low proportion of female students and researchers. In the EU there are on average 33% female PhD graduates in the physical sciences, while the percentage of female professors amounts to 9% (ECDGR 2006). At CERN the proportion is even less, with only 6.6% of the research staff in experimental and theoretical physics being women (Schinzel 2006). The fact that there is no proportional relationship between the number of PhD graduates and professors also suggests that women are less likely to succeed in an academic career than men.

Before examining the findings of various studies, it is worth asking if this low representation of women in physics is a problem – do we actually need more female physicists? In my opinion this question has to be answered from three perspectives: the perspective of society, the perspective of science and the perspective of women.

Starting from the viewpoint of society, there are several issues to consider. First, physics is a field of innovation. Many technological advancements that have a huge impact on society and everyday life come directly or indirectly from physics. Being a physicist therefore means having access to people and knowledge that set the technological agenda.

Second, in many countries research and academic positions are regarded as high-status jobs. Academic staff are often appointed to committees that fund research projects or advise governments on issues that are closely related to their field of expertise. As such, scientists influence the focus of research and the general development of society.

Finally, it is a democratic principle that power and influence should be distributed equally and proportionally among different groups in society. An EU average of 9% female physics professors does not even come close to equal representation in this field. The fact that women fund research through tax payments adds to the demand for more female scientists.

From a scientific point of view, the lack of women represents a huge waste of talent. For physics to develop further as a science, it needs more people with excellent analytical, communicational and social skills. There are also reports that departments without women suffer in many ways (Main 2005).

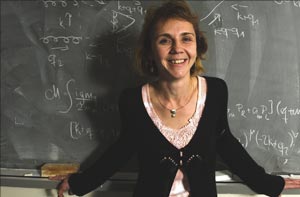

From the perspective of women, they will of course benefit from increased influence in society, but contributing to physics is not only about struggling for influence and power. Fundamental questions have been asked throughout history by men and women alike. Contributing to physics is to participate in a human project, driven by curiosity and wonder that seeks to understand the world around us.

What the studies find

So why do women fail to advance to the top levels in academia? Some reports state that it is because women are less likely to give priority to their career (Pinker and Spelke 2005), while others cite inferiority in the ability to do science compared with men or the lack of some of the abilities necessary to be successful in science. For example, one report suggests that men are on average more aggressive than women, and that this characteristic (among others) is necessary to succeed in academic work (Lawrence 2006). What these reports have in common is that they all conclude that there will never be as many women as men in academia because of innate differences between the genders, and also that these differences are the main reason for the under-representation of women.

Other reports state that women do not succeed in physics because of prejudice, discrimination and unfriendly attitudes towards them. Studies have shown that women need to be twice as productive as men to be considered equally competent (Wennerås and Wold 1997). In fact both men and women rate men’s work higher than that of women (Goldberg 1968). There is also the psychological mechanism called “stereotype threat”, which causes individuals who are made aware of the negative stereotypes connected to the social group to which they belong – such as age, gender, ethnicity and religion – to underperform in a manner consistent with the stereotype. White male engineering students will for instance perform significantly worse on tests when they are told that Asian students usually outperform them on the same tests (Steele 2004). It is important to remember that these prejudices are present in most human beings and do not necessarily arise from bad will or conscious hostility.

A survey designed to identify issues that are important to female physicists also reported on their negative experiences as a minority group owing to the male domination in the field (Ivie and Guo 2005). In this survey 80% state that attitudes towards women in physics need to be improved, while 65% believed discrimination is a problem that needs to be dealt with. This survey also reported on positive experiences among female physicists, in particular their love for their field and the support that they have received from others.

To produce an exhaustive list of reasons for why so few women are able to reach the highest positions in academia would be a tedious endeavour with many conflicting opinions. However, if we agree that we need more women in physics, it is clear that we need to take action. In this regard it is important to recognize that some of these actions will also be beneficial to men, improving their ability to succeed in a scientific career.

In academia several things can be changed to eliminate discrimination and hostile attitudes towards women (and men):

• Transparency in selection processes for scholarships, funding and positions, i.e. making all evaluation done by the selection committees public so that any discriminating mechanism can be unveiled. This will also benefit men, since they are also subjects of discrimination (Wennerås and Wold 1997).

• Investigate hostile attitudes in institutes and laboratories. Those who discriminate tend not to see how their behaviour affects their environment, and those discriminated against are usually reluctant to admit it. The Institute of Physics in London visits institutes, on invitation only, to investigate their attitudes towards women (Main 2005).

• Make the career path more predictable. Both genders suffer from the unpredictability and requirement of mobility in an academic physics career, and this can also conflict with the desire to start a family (Ivie and Guo 2005).

• Awareness of discrimination. Nobody wants to discriminate against others; the use of stereotypes and prejudice is a part of the human mind. It is therefore important to be aware of how these properties affect the way that we evaluate and treat others. Awareness of discriminating procedures have caused changes. Both the US National Institutes of Health (Carnes 2006) and the Swedish Medical Research Council (Wennerås and Wold 1997) changed their routines after being made aware that their evaluation and recruitment schemes were prejudiced against women.

There is no doubt that the under-representation of women in physics is a sensitive issue. Women and men who have never experienced discrimination or bias towards their gender often feel repelled when the issue is discussed. However, I believe the numbers speak for themselves: women do not have the same possibility to succeed in academia as men. As individuals we would like to think that we can all approach any branch of society without being met with hostility or bias, no matter what ethnic group, social class, religion or gender we might belong to. In the end most women would just like to be able to make the same mistakes, produce the same number of papers and be respected, accepted or rejected on the same conditions as their male colleagues, not more, not less.

• With thanks to the ATLAS Women Group, David Milstead, Robindra Prabhu, Helene Rickhard, Josi Schinzel, Jonas Strandberg and Sara Strandberg.