Almost a decade after ATOMKI researchers reported an unexpected peak in electron–positron pairs from beryllium nuclear transitions, the case for a new “X17” particle remains open. Proposed as a light boson with a mass of about 17 MeV and very weak couplings, it would belong to the sometimes-overlooked low-energy frontier of physics beyond the Standard Model. Two recent results now pull in opposite directions: the MEG II experiment at the Paul Scherrer Institute found no signal in the same transition, while the PADME experiment at INFN Frascati reports a modest excess in electron–positron scattering at the corresponding mass.

The story of the elusive X17 particle began at the Institute for Nuclear Research (ATOMKI) in Debrecen, Hungary, where nuclear physicist Attila János Krasznahorkay and colleagues set out to study the de-excitation of a beryllium-8 state. Their target was the dark photon – a particle hypothesised to mediate interactions between ordinary and dark matter. In their setup, a beam of protons strikes a lithium-7 target, producing an excited beryllium nucleus that releases a proton or de-excites to the beryllium-8 ground state by emitting an 18.1 MeV gamma ray – or, very rarely, an electron–positron pair.

Controversial anomaly

In 2015, ATOMKI claimed to have observed an excess of electron–positron pairs with a statistical significance of 6.8σ. Follow-up measurements with different nuclei were also reported to yield statistically significant excess at the same mass. The team claimed the excess was consistent with the creation of a short-lived neutral boson with a mass of about 17 MeV. Given that it would be produced in nuclear transitions and decay into electron–positron pairs, the X17 should couple to nucleons, electrons and positrons. But many relevant constraints squeeze the parameter space for new physics at low energies, and independent tests are essential to resolve an unexpected and controversial anomaly that is now a decade old.

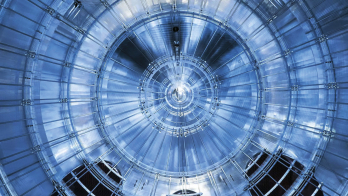

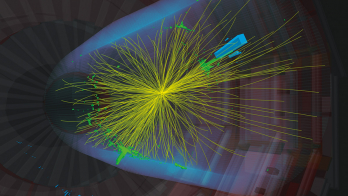

In November 2024, MEG II announced a direct cross-check of the anomaly, publishing their results in July 2025. Designed for high-precision tracking and calorimetry, the experiment combines dedicated background monitors with a spectrometer based on a lightweight, single-volume drift chamber that records the ionisation trails of charged particles. The detector is designed to search for evidence of the rare lepton-flavour-violating decay μ+ → e+γ, with the collaboration recently reporting world-leading limits at EPS-HEP (see “High-energy physics meets in Marseille”). It is also well suited to probing electron–positron final states, and has the mass resolution required to test the narrow-resonance interpretation of the ATOMKI anomaly.

Motivated by interest in X17, the collaboration directed a proton beam with energy up to 1.1 MeV onto a lithium-7 target, to study the same nuclear process as ATOMKI. Their data disfavours the ATOMKI hypothesis and imposes an upper limit on the branching ratio of 1.2 × 10–5 at 90% confidence.

“While the result does not close the case,” notes Angela Papa of INFN, the University of Pisa and the Paul Scherrer Institute, “it weakens the simplest interpretations of the anomaly.”

But MEG II is not the only cross check in progress. In May, the PADME collaboration reported an independent test that doesn’t repeat the ATOMKI experiment, but seeks to disentangle the X17 question from the complexities of nuclear physics.

For theorists, X17 is an awkward fit

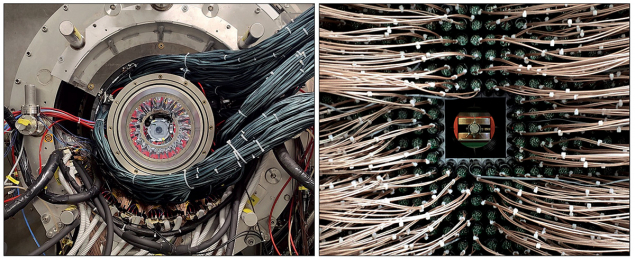

Initially designed to search for evidence of states that decay invisibly, like dark photons or axion-like particles, PADME collides a positron beam with energies reaching 550 MeV with a 100 µm-thick active diamond target. Annihilations of positrons with electrons bound in the target material are reconstructed by detecting the resulting photons, with any peak in the missing-mass spectrum signalling an unseen product. The photon energy and impact position is measured by a finely segmented electromagnetic calorimeter with crystals refurbished from the L3 experiment at LEP.

“The PADME approach relies only on the suggested interaction of X17 with electrons and positrons,” remarks spokesperson Venelin Kozhuharov of Sofia University and INFN Frascati. “Since the ATOMKI excess was observed in electron–positron final states, this is the minimal possible assumption that can be made for X17.”

Instead of searching for evidence of unseen particles, PADME varied the beam energy to look for an electron-positron resonance in the expected X17 mass range. The collaboration claims that the combined dataset displays an excess near 16.90 MeV with a local significance of 2.5σ.

For theorists, X17 is an awkward fit. Most consider dark photons and axions to be the best motivated candidates for low mass, weakly coupled new physics states, says Claudio Toni of LAPTh. Another possibility, he says, is a bound state of known particles, though QCD states such as pions are about eight times heavier, and pure QED effects usually occur at much lower scales than 17 MeV.

“We should be cautious,” says Toni. “Since X17 is expected to couple to both protons and electrons, the absence of signals elsewhere forces any theoretical proposal to respect stringent constraints. We should focus on its phenomenology.”

Further reading

MEG II Collab. 2025 Eur. Phys. J. C 85 763.

PADME Collab. 2025 arXiv:2505.24797.