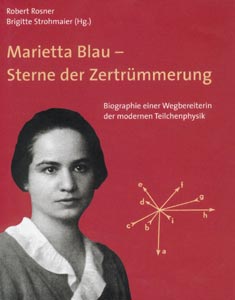

by Robert Rosner and Birgitte Strohmaier (eds), Böhlau Verlag. ISBN 3205770889, €29.90.

Marietta Blau – Sterne der Zertrümmerung (stars of fragmentation) is the third in a new series devoted to scientists from Austrian history, following on from those about Hans Thirring and Ludwig Boltzmann.

In brief, Marietta Blau was born in Vienna in 1894 to a moderately well-to-do Jewish family, and was among the first women to study physics at the University of Vienna. In 1923 she joined the Radium Institute in Vienna, but was forced into exile in 1938. After five years in Mexico and 16 years in the US she returned to her native Austria in 1960, aged 66 and badly in need of medical treatment. She died of cancer in Vienna in 1970.

The book begins with a long and well-documented biographic chapter written by the editors. Here the history of the Radium Institute is described so vividly that I had the feeling I was actually moving around the building and meeting the people working there. The reader is presented with some interesting and at times surprising details.

For example, more than one-third of the researchers at the Radium Institute were women and the majority of Blau’s PhD students were female. However, this was not a general phenomenon during the 1930s. After leaving Austria, aided by Albert Einstein, Blau found refuge in Mexico as a staff member at the Polytechnic Institute in Mexico City between 1939 and 1944. One of the pictures in the book shows the teaching staff at the institute in 1940, and out of 58 people in the photo, Blau is the only woman. (It is interesting to compare this with our own time. A recent picture in CERN Courier shows the participants at a conference on supergravity, and three out of the 52 are women.)

Another surprising fact is that the majority of the researchers at the Radium Institute, both male and female and including Blau, were unpaid. Perhaps they were working there simply to have a meaningful life? The book quotes the famous Austrian physicist Lise Meitner to have said in 1963: “I believe that all young people think about how they would like their lives to develop. When I did so, I always arrived at the conclusion that life need not be easy; what is important is that it not be empty. And this wish I have been granted.”

The book also describes how Blau turned down academic job offers during her most productive years to take care of her sick mother, and her close collaboration with Hertha Wambacher (1903-1950), who having originally studied chemistry had turned to physics and chosen Blau as her supervisor. After Wambacher had finished her doctorate, the two women had an extensive and fruitful collaboration for the next six years, in particular in trying to improve the emulsion technique for detecting particles. However, much of their relationship remains a great mystery. Wambacher was a member of the Nazi party, but obituaries for her shed no light on this matter as they deal exclusively with her work.

Other topics covered in detail include Blau’s work before and after the Second World War, and there are reminiscences from those who had contact with Blau in the latter stages of her career when she was in her sixties. Blau’s last PhD student worked from 1960 to 1964 analysing an experiment done at CERN in which emulsions were exposed to a beam of protons. This was one of a large number of experiments at CERN at this time that used emulsions. At the end of the book there is a reprint of three of Blau’s papers, two of which were with Wambacher, and a list of all her publications.

Blau was an expert on nuclear emulsions, a detection technique with old roots. In 1937 she and Wambacher observed 31 “stars” in emulsions exposed to cosmic rays. The stars were made by collisions in the emulsions, which produced several particle tracks emanating from the collision point; one of the stars had no less than 12 tracks! The observation of these stars drew the attention of the scientific community to emulsions, which were considered by some as being rather out of date. However, to claim that the work by Blau and Wambacher was a prerequisite for the discovery of the pion is a gross exaggeration. Emulsions had to be enormously improved to achieve the required sensitivity. One of the authors in the book also claims that Blau must have been frustrated that Cecil Powell was awarded the Nobel prize for a discovery using her method, so much so that she erroneously attributed the first observation of the negative pion to Don Perkins. However, this speculation is unfounded; Blau was in fact giving a correct account of what had happened. Another point made concerns the nomination of Blau and Wambacher for the Nobel Prize in Physics. By itself this is not a measure of the highest excellence as every year there are a large number of such nominations.

The literature on emulsion techniques is vast and it is very difficult to do justice to all those who have contributed to this field. Nonetheless, I was deeply touched by the portrait of this exceptional woman, described as shy, gentle and highly dedicated to her métier, but who had the misfortune to live in a hostile environment, a victim of a sick society.