by François Vannucci, Odile Jacob. ISBN 2738113311, €23.50.

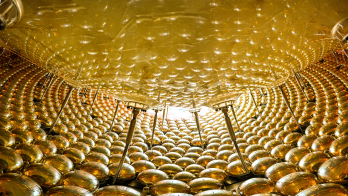

Neutrinos have excited scientists since 1930 and have allowed some important discoveries: Gargamelle’s 1973 observation of neutral currents in fact constituted the first manifestation of the Z boson, and as such marked the experimental foundation of the Standard Model. More recently, the beautiful phenomenon of neutrino oscillations has demonstrated that the Standard Model needs to be enlarged to account for neutrino masses. In a nutshell, neutrinos are in the spotlight.

For this reason it is very pleasant to see one of our colleagues undertake to communicate to a broad public his enthusiasm and excitement for these particles that are so hard to detect. The “mirror” through which Vannucci invites us to discover these neutrinos is, in the end, that of his own personality. The reader finds a typically French character, profoundly cultured, who revels in the company of literary quotes that mirror his thoughts and that enrich them with a touch of melancholic beauty. Marcel Proust and Oscar Wilde top his favourite author’s list, which extends from Saint Augustine to Daniel Pennac, via Jean-Paul Sartre and the medical dictionary. Sometimes a school-boy’s wink, and often a sensuous shiver, express themselves through these quotations, which is testimony to the fact that science speaks not only to the brain but also the heart. I am not sure that I have grasped what these quotations are supposed to explain, but they certainly carry a form of emotion.

The book tells the story of neutrinos, at a level that is meant to be accessible to pupils in the final years of high school (15-18 years old), as well as scientifically cultivated adults. It begins with a discussion of perception and detection, first of ordinary objects and then of particles. Then we arrive at Pauli and his “radioactive ladies and gentlemen”, followed immediately by UA1 and the discovery of the W. (Sartre and Le Verrier are quoted…but no word of Carlo Rubbia. This will soothe the feelings of all those who felt they should have appeared.) Then we go back to the experiments to measure the neutrino mass followed by neutrinoless double-beta decay, and the detection of the first neutrino interactions by Fred Reines. As one can see, the experiments that have established the properties of neutrinos are listed thematically and not necessarily historically, something that I appreciated.

With occasional irony towards his colleagues (or himself?), Vannucci takes us around the experiments that made history in neutrino physics; those that were right and those that were wrong, those that made us understand and those that got us confused. This is followed by a discussion on uncertainties and the scientific method. I am not sure I agree fully when what we don’t know yet but are striving to know and will hopefully understand (“the big bang cannot be considered a physical event”), is compared with medieval legends (“angels, archangels and cherubim of the middle ages”). However, do read carefully and you will find the definition of the “miroir aux alouettes”, which inspired the title of the book and is taken from a quotation in…a dictionary.

It is not obvious for whom this book is best suited. For whom would I buy it? It seems more for our fathers – and mothers – or our colleagues than for teenagers, who may be discouraged by the unlikely mix of literature and science.