Astrophysical constraints stake out 90 orders of magnitude for the mass of dark-matter particles. Clara Murgui surveys this vast terrain before zooming in on a particularly interesting region of parameter space: the post-inflation QCD axion.

There is an overwhelming amount of evidence for the existence of dark matter in our universe. This type of matter is approximately five times more abundant than the matter that makes up everything we observe: ourselves, the Earth, the Milky Way, all galaxies, neutron stars, black holes and any other imaginable structure.

We call it dark because it has not yet been probed through electroweak or strong interactions. We know it exists because it experiences and exerts gravity. That gravity may be the only bridge between dark matter and our own “baryonic” matter, is a scenario that is as plausible as it is intimidating, since gravitational interactions are too weak to produce detectable signals in laboratory-scale experiments, all of which are made of baryonic matter.

However, dark matter may interact with ordinary matter through non-gravitational forces as well, possibly mediated by new particles. Our optimism is rooted in the need for new physics. We also require new mechanisms to generate neutrino masses and the matter–antimatter asymmetry of the universe, and these new mechanisms may be intimately connected to the physics of dark matter. This view is reinforced by a surprising coincidence: the abundances of baryonic and dark matter are of the same order of magnitude, a fact that is difficult to explain without invoking a non-gravitational connection between the two sectors.

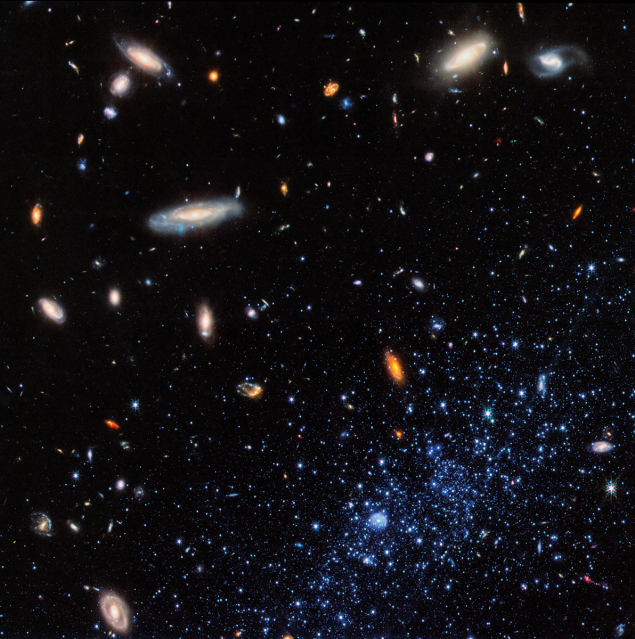

It may be that we have not yet detected dark matter simply because we are not looking in the right place. Like good sailors, the first question we ask is how far the boundaries of the territory to be explored extend. Cosmological and astrophysical observations allow dark-matter masses ranging from ultralight values of order 10–22 eV up to masses of the order of thousands of solar masses. The lower bound arises from the requirement that the dark-matter de Broglie wavelength not exceed the size of the smallest gravitationally bound structures, dwarf galaxies, such that quantum pressure does not suppress their formation (see “Leo P” image). The upper limit can be understood from the requirement that dark matter behave as a smooth, effectively collision-less medium on these small astrophysical structures. This leaves us with a range of possibilities spanning about 90 orders of magnitude, a truly overwhelming landscape. Given that our resources, and our own lifetimes, are finite, we guide our expedition both by theoretical motivation and the capabilities of our experiments to explore this vast territory.

Dark matter could be connected to the Standard Model in alternative ways

The canonical dark-matter candidate where theoretical motivation and experimental capability coincides is the weakly interacting massive particle. “WIMPs” are among the most theoretically economical dark-matter candidates, as they naturally arise in theories with new physics at the electroweak scale and can achieve the observed relic abundance through weak-scale interactions. The latter requirement implies that the mass of thermal WIMPs must lie above the GeV scale – approximately a nucleon mass. This “Lee–Weinberg” bound arises because lighter particles would not have annihilated fast enough in the early universe, leaving behind far more dark matter than we observe today.

WIMPs can be probed using a wide range of experimental strategies. At high-energy colliders, searches rely on missing transverse energy, providing sensitivity to the production of dark-matter particles or to the mediators that connect the dark and visible sectors. Beam dump and fixed-target experiments offer complementary sensitivity to light mediators and portal states. Direct-detection experiments measure nuclear recoils of heavy and stable targets, such as noble liquids like xenon or argon, which are sensitive to energy depositions at the keV scale, allowing us to probe dark-matter masses in the light end of the typical WIMP range with extraordinary sensitivity.

Light dark matter

So far, no conclusive signal has been observed, and the simplest realisations of the WIMP paradigm are becoming increasingly constrained. However, dark matter could be connected to the Standard Model in alternative ways, for example through new force carriers, allowing its mass to fall below the Lee–Weinberg bound. This sub-GeV dark matter, also referred to as light dark matter, appears in highly motivated theoretical frameworks such as asymmetric dark matter, in which an asymmetry between dark-matter particles and antiparticles sets the relic abundance, analogously to the baryon asymmetry that determines the visible matter abundance. In some of the best motivated realisations of this scenario, the dark-matter candidate resides in a confining “hidden sector” (see, for example, “Soft clouds probe dark QCD”). A dark-baryon symmetry may guarantee the stability of such composite dark-matter states, with the baryonic and dark asymmetries being generated by related mechanisms.

Dark matter could be even lighter and behave as a wave. This occurs when its mass is below the eV-to-10 eV scale, comparable to the ionisation energy of hydrogen. In this case, its de Broglie wavelength exceeds the typical separation between particles, allowing it to be described as a coherent, classical field. In the ultralight dark-matter regime, the leading candidate is the axion. This particle is a prediction of theories beyond the Standard Model that provide a solution to the strong charge–parity (CP) problem.

In the Standard Model, there is no fundamental reason for CP to be conserved by strong interactions. In fact, two terms in the Lagrangian, of very different origin, contribute to an effective CP-violating angle, which would generically induce an electric dipole moment of hadrons, corresponding phenomenologically to a misalignment of their electromagnetic charge distributions. But remarkably – and this is at the heart of the puzzle – high-precision experiments measuring the neutron electric dipole moment show that this angle cannot be larger than 10–10 radians.

Why is this? To quote Murray Gell-Mann, what is not forbidden tends to occur. This unnaturally precise alignment in the strong sector strongly suggests the presence of a symmetry that forces this angle to vanish.

One of the most elegant and widely studied solutions, proposed by Roberto Peccei and Helen Quinn, consists of extending the Standard Model with a new global symmetry that appears at very high energies and is later broken as the universe cools. Whenever such a symmetry breaks, the theory predicts the appearance of one or more new, extremely light particles. If the symmetry is not perfect, but is slightly disturbed by other effects, this particle is no longer exactly massless and instead acquires a small mass controlled by the symmetry-breaking effects. A familiar example comes from ordinary nuclear physics: pions are light particles because the symmetry that would make them massless is slightly broken by the tiny masses of its constituent quarks.

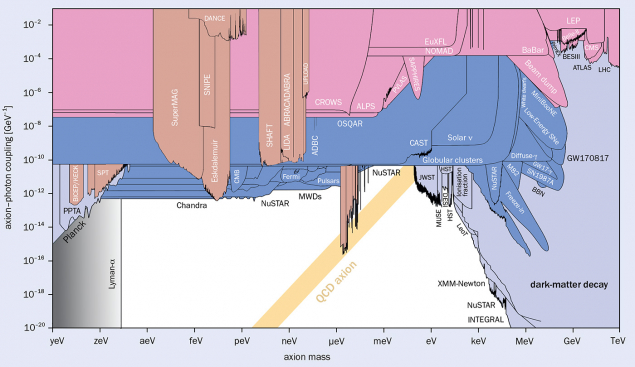

In this framework, the new light particle is called the axion, independently proposed by Steven Weinberg and Frank Wilczek. The axion has remarkable properties: it naturally drives the unwanted CP-violating angle to zero, and its interactions with ordinary matter are not arbitrary but tightly controlled by the same underlying physics that gives it its tiny mass. Strong-interaction effects predict a narrow, well-defined “target band” relating how heavy the axion is to how strongly it interacts with matter, providing a clear roadmap for current experimental searches (the yellow band in the “In pursuit of the QCD axion” figure).

An excellent candidate

Axions also emerge as excellent dark-matter candidates. They can account for the observed cosmic dark matter through a purely dynamical mechanism in which the axion field begins to oscillate around the minimum of its potential in the early universe, and the resulting oscillations redshift as non-relativistic dark matter. Inflation is a little understood rapid expansion of the early universe by more than 26 orders of magnitude in scale factor that cosmologists invoke to explain large-scale correlations in the cosmic microwave background and cosmic structure. If the Peccei–Quinn symmetry was broken after inflation, the axion field would take random initial values in different regions of space, leading to domains with uncorrelated phases and the formation of cosmic strings. Averaging over these regions removes the freedom to tune the initial angle and makes the axion relic density highly predictive. When the additional axions from cosmic strings and domain walls are included, this scenario points to a well defined axion mass in the tens to few-hundreds of μeV range.

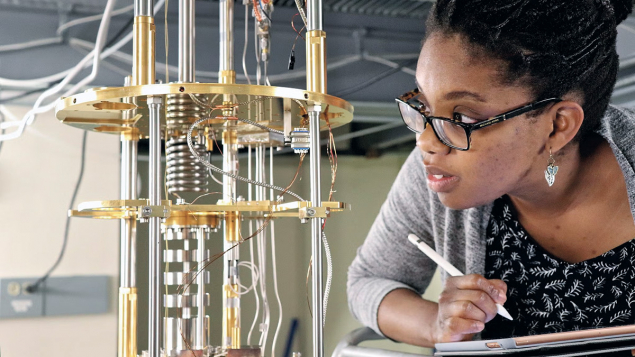

There is now a wide array of ingenious experiments, the result of the work of large international collaborations and decades of technological development, that aim to probe the QCD-axion band in parameter space. Despite the many experimental proposals, so far only ADMX, CAPP and HAYSTAC have reached sensitivities close to this target (see “Cavity haloscope” image). These experiments, known as haloscopes, operate under the assumption that axions constitute the dark matter in our universe. In these setups, a high–quality-factor electromagnetic cavity is placed inside a strong magnetic field in which axions from the dark-matter halo of the Milky Way are expected to convert into photons. The resonant frequency of the cavity is tuned like a radio scanning axion masses. This technique allows experiments to probe couplings many orders of magnitude weaker than typical Standard Model interactions. However, scaling these resonant experiments to significantly different axion masses is challenging as a cavity’s resonant frequency is tied to its size. Moving away from its optimal axion-mass range either forces the cavity volume to become very small, reducing the signal power, or requires geometries that are difficult to realise in a laboratory environment.

Other experimental approaches, such as helioscopes, focus on searching for axions produced in the Sun. These experiments mainly probe the higher-mass region of the QCD-axion band and also place strong constraints on axion-like particles (ALPs). ALPs are also light fields that arise from the breaking of an almost exact global symmetry, but unlike the QCD axion, the symmetry is not explicitly broken by strong-interaction effects, so their masses and couplings are not fixedly related. While such particles do not solve the strong CP problem, they can be viable dark-matter candidates that naturally arise in many extensions of the Standard Model, especially in theories with additional global symmetries and in quantum-gravity frameworks.

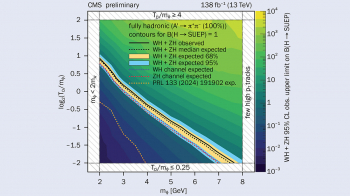

Among the proposed experimental efforts to observe post-inflation QCD axions, two stand out as especially promising: MADMAX and ALPHA. Both are haloscopes, designed to detect QCD axions in the galactic dark-matter halo. Neither is traditional. Each uses a novel detector concept to target higher axion masses – a regime that is especially well motivated if the Peccei–Quinn symmetry is broken after inflation (see “In pursuit of the post-inflation axion”).

We are living in an exciting era for dark-matter research. Experimental efforts continue and remain highly promising. A large and well-motivated region of parameter space is likely to become accessible in the near future, and upcoming experiments are projected to probe a significant fraction of the QCD axion parameter space over the coming decades. Clear communication, creativity, open-mindedness in exploring new ideas, and strong coordination and sharing of expertise across different physics communities, will be more important than ever.