At his 80th birthday event at Fermilab, former laboratory deputy director, Ned Goldwasser, recalled Fermilab’s early days, when human rights were as important as protons.

Present at the beginnings of a great adventure in high-energy physics, former laboratory deputy director Ned Goldwasser will not forget the long hot summers of the mid-1960s: a formative time for Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory and an era when turmoil raged from coast to coast in the US.

There were major fires and riots in Watts (Los Angeles), Detroit, Washington DC (where the National Guard had tanks in the streets) and the South Bronx and Bedford-Stuyvesant areas of New York City.

Before a building had been raised on the 6800 acre laboratory site in March 1967, newly named director Robert R Wilson telephoned Goldwasser, then at Illinois, asking him to come on board the project.

Goldwasser, who had served on the committee that recommended potential sites for the new laboratory to the US Atomic Energy Commission, took the job and agreed to visit Wilson at Cornell. When they met, they spoke not only about relationships in particle physics but also about relationships among people.

At The Early Days of Fermilab, a mini-symposium honouring his 80th birthday, Goldwasser recalled: “We spent a large fraction of that meeting discussing our independent but similar notions that the opportunity of building a lab at that time, with what was happening in the country, was an opportunity that shouldn’t be missed.

“We wanted to demonstrate that such a project could be started and run in a manner sensitive to some of the racial problems the country was suffering from. Cities were burning. There were large-scale protests against discrimination. Bob felt, and I agreed, that we could and should do something to address those problems.”

Beam or bust

The first speaker at the symposium was Norman Ramsey, 1989 Nobel Prizewinner for his invention of the separated oscillatory fields method and its use in the hydrogen maser and other atomic clocks. Ramsey was the first president of the Universities Research Association, the consortium that manages Fermilab for the US Department of Energy.

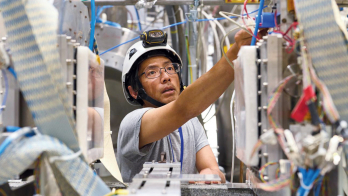

Bill Fowler, currently associate project manager for Fermilab’s Main Injector, joined Fermilab in 1970 to construct the 15 ft hydrogen bubble chamber. He later served as Wilson’s deputy project leader in developing the Tevatron. Fowler summed up the feeling of the lab’s early days as: “Co-operation we had it at that time.”

However, those early days are also characterized by the crisis management, “beam or bust” outlook described by Rich Orr, who served the lab in many capacities over 20 years. Orr lauded Wilson and Goldwasser as being “responsible for how Fermilab became Fermilab, as opposed to what it set out to become”.

In those early days, buildings were put up before funds were authorized. “We try to start before we’ve been approved so we know we can finish,” joked current director John Peoples.

We worked all night, but we didn’t get it

Ned Goldwasser

Even in the winter of the Cold War, researchers were welcomed from the Soviet Union. Physics experiments transcended international politics. “Experiments were open to users from all areas,” said Yoshio Yamaguchi, a former president of the International Union of Pure and Applied Physics.”I’m very glad that high-energy physics started such a wonderful idea.”

Goldwasser remembers a Soviet VIP visit. The new lab’s goal was to have beams circulating around the entire Main Ring. “We worked all night, but we didn’t get it,” Goldwasser said. “The whole Soviet entourage was there and we said we were sorry, but we weren’t able to get it done. Later, the Soviet commissioner told Bob Wilson such an admission had been very stupid. ‘In the Soviet Union,’ he said, ‘we have learned that it doesn’t matter. They don’t know if it’s a full turn or not. We just tell them we made a full turn and that’s just as good.’ ”

Civil rights

Those early days were full of hope for the future of physics. However, with the cities burning, the civil rights struggle and national politics were uppermost in people’s minds.

“My feeling,” Goldwasser said, “is that President Lyndon Johnson made the decision at least in some measure as a trade-off with Illinois Senator Everett Dirksen.”

Democrat Johnson, who became President in 1963 following the assassination of John F Kennedy, set great store by passing civil rights legislation to heal the country. He also held a longstanding interest in Big Science from his years as vice-president. NASA had been his particular area of responsibility, and the Johnson Space Flight Center, in his native state of Texas, is named in his honour.

“The Federal Open Housing Bill [to desegregate housing officially] was before Congress,” said Goldwasser. “Everyone knew that the vote in the Senate would be very close. What surprised everyone was that [Republican] Dirksen, who had a long record of strong positions against anything in the nature of open housing, withheld his vote to the end, then he cast in favour of the bill, to break a tie.”

Although open housing became the law of the land, its implementation was not immediate everywhere. The Revd Martin Luther King, angry that at the state level Illinois soundly rejected a similar bill, threatened to lead demonstrations blocking the construction of the laboratory in Illinois. The subject of racial tensions dominated the first official meeting of the National Accelerator Laboratory on 15 June 1967 at the design offices in Oak Brook.

Affirmative action

Goldwasser recalled: “Bob asked me to take on the job of going into Chicago and meeting with the leaders of minority groups in an effort to persuade them that we intended to have a very active programme for what would now be called affirmative action. There was no such thing in those days, but we told them we expected to find employment for minority people and we expected to try to recruit many of them from among the inner-city gangs in Chicago.

“Those were some of my interesting days. I met with leaders of the Urban League and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, but I also met with leaders of the Black Panthers, as well as with gangs in Chicago. I told them what our intentions were and asked them to give us ideas about how we might proceed.”

Soon the informal affirmative action programme managed to take a major step forward when Ken Williams joined the lab from one of the local hospitals. He headed the lab’s affirmative action efforts for many years.

“The first thing he did was a great relief to me,” said Goldwasser. “He took over the responsibility of going into the city and meeting with the gangs. In those meetings he interviewed individual gang members, trying to evaluate who was really serious about getting out of gang life and getting a real job in the outside world. I felt he had unerring taste and judgement in the people he chose.”

The lab and community leaders cobbled together a programme taking kids out of city gangs and sending them to a six-month technical training programme. Those who stayed the course would return to the lab with jobs as technicians. Training was at Oak Ridge, and spending six months in Tennessee in the 1960s might have seemed daunting to young black men from Chicago, but it worked. “Around the time I left the lab [in 1978], I think we were about 90% successful in retaining those trainees. And most of the people who left had gone on to better jobs. Ken Williams made an enormous contribution to the laboratory,” Goldwasser said.

Within the first year of the lab’s operation, Wilson and Goldwasser had also issued a policy statement on human rights. Goldwasser read from its final paragraph: “Our support of the rights of the members of minority groups in our laboratory and in its environs is inextricably intertwined with our goal of creating a new centre of technical and scientific excellence.”

Against a background of racial turmoil, the human rights focus of Goldwasser, Robert Wilson and all of those involved at the start of what was to become Fermilab demonstrated clearly their commitment to principles beyond science.