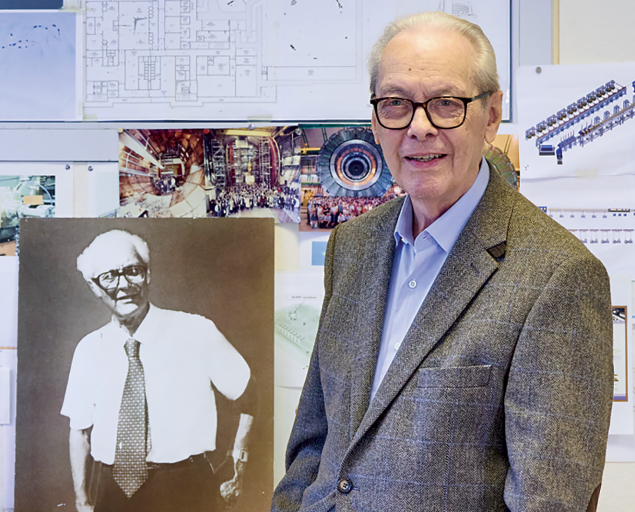

In an interview drawing on memories from childhood and throughout his own distinguished career at CERN, Ugo Amaldi offers deeply personal insights into his father Edoardo’s foundational contributions to international cooperation in science.

Should we start with your father’s involvement in the founding of CERN?

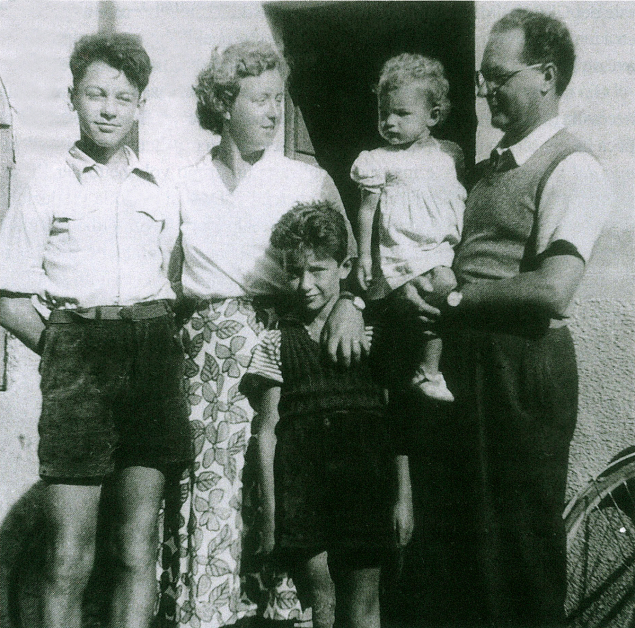

I began hearing my father talk about a new European laboratory while I was still in high school in Rome. Our lunch table was always alive with discussions about science, physics and the vision of this new laboratory. Later, I learned that between 1948 and 1949, my father was deeply engaged in these conversations with two of his friends: Gilberto Bernardini, a well-known cosmic-ray expert, and Bruno Ferretti, a professor of theoretical physics at Rome University. I was 15 years old and those table discussions remain vivid in my memory.

So, the idea of a European laboratory was already being discussed before the 1950 UNESCO meeting?

Yes, indeed. Several eminent European physicists, including my father, Pierre Auger, Lew Kowarski and Francis Perrin, recognised that Europe could only be competitive in nuclear physics through collaborative efforts. All the actors wanted to create a research centre that would stop the post-war exodus of physics talent to North America and help rebuild European science. I now know that my father’s involvement began in 1946 when he travelled to Cambridge, Massachusetts, for a conference. There, he met Nobel Prize winner John Cockcroft, and their conversations planted in his mind the first seeds for a European laboratory.

Parallel to scientific discussions, there was an important political initiative led by Swiss philosopher and writer Denis de Rougemont. After spending the war years at Princeton University, he returned to Europe with a vision of fostering unity and peace. He established the Institute of European Culture in Lausanne, Switzerland, where politicians from France, Britain and Germany would meet. In December 1949, during the European Cultural Conference in Lausanne, French Nobel Prize winner Louis de Broglie sent a letter advocating for a European laboratory where scientists from across the continent could work together peacefully.

My father strongly believed in the importance of accelerators to advance the new field that, at the time, was at the crossroads between nuclear physics and cosmic-ray physics. Before the war, in 1936, he had travelled to Berkeley to learn about cyclotrons from Ernest Lawrence. He even attempted to build a cyclotron in Italy in 1942, profiting from the World’s Fair that had to be held in Rome. Moreover, he was deeply affected by the exodus of talented Italian physicists after the war, including Bruno Rossi, Gian Carlo Wick and Giuseppe Cocconi. He saw CERN as a way to bring these scientists back and rebuild European physics.

How did Isidor Rabi’s involvement come into play?

In 1950 my father was corresponding with Gilberto Bernardini, who was spending a year at Columbia University. There Bernardini mentioned the idea of a European laboratory to Isidor Rabi, who, at the same time, was in contact with other prominent figures in this decentralised and multi-centered initiative. Together with Norman Ramsay, Rabi had previously succeeded, in 1947, in persuading nine northeastern US universities to collaborate under the banner of Associated Universities, Inc, which led to the establishment of Brookhaven National Laboratory.

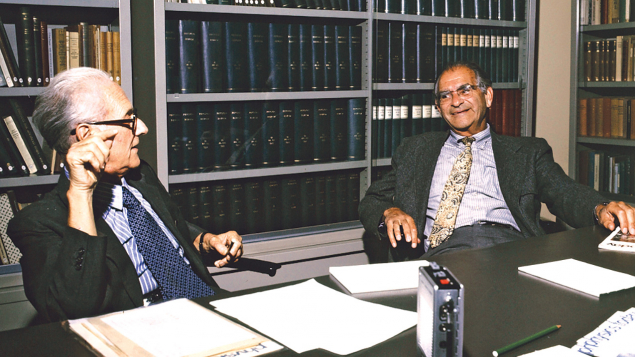

What is not generally known is that before Rabi gave his famous speech at the fifth assembly of UNESCO in Florence in June 1950, he came to Rome and met with my father. They discussed how to bring this idea to fruition. A few days later, Rabi’s resolution at the UNESCO meeting calling for regional research facilities was a crucial step in launching the project. Rabi considered CERN a peaceful compensation for the fact that physicists had built the nuclear bomb.

How did your father and his colleagues proceed after the UNESCO resolution?

Following the UNESCO meeting, Pierre Auger, at that time director of exact and natural sciences at UNESCO, and my father took on the task of advancing the project. In September 1950 Auger spoke of it at a nuclear physics conference in Oxford, and at a meeting of the International Union of Pure and Applied Physics (IUPAP), my father– one of the vice presidents – urged the executive committee to consider how best to implement the Florence resolution. In May 1951, Auger and my father organised a meeting of experts at UNESCO headquarters in Paris, where a compelling justification for the European project was drafted.

The cost of such an endeavour was beyond the means of any single nation. This led to an intergovernmental conference under the auspices of UNESCO in December 1951, where the foundations for CERN were laid. Funding, totalling $10,000 for the initial meetings of the board of experts, came from Italy, France and Belgium. This was thanks to the financial support of men like Gustavo Colonnetti, president of the Italian Research Council, who had already – a year before – donated the first funds to UNESCO.

Were there any significant challenges during this period?

Not everyone readily accepted the idea of a European laboratory. Eminent physicists like Niels Bohr, James Chadwick and Hendrik Kramers questioned the practicality of starting a new laboratory from scratch. They were concerned about the feasibility and allocation of resources, and preferred the coordination of many national laboratories and institutions. Through skilful negotiation and compromise, Auger and my father incorporated some of the concerns raised by the sceptics into a modified version of the project, ensuring broader support. In February 1952 the first agreement setting up a provisional council for CERN was written and signed, and my father was nominated secretary general of the provisional CERN.

He worked tirelessly, travelling through Europe to unite the member states and start the laboratory’s construction. In particular, the UK was reluctant to participate fully. They had their own advanced facilities, like the 40 MeV cyclotron at the University of Liverpool. In December 1952 my father visited John Cockcroft, at the time director of the Harwell Atomic Energy Research Establishment, to discuss this. There’s an interesting episode where my father, with Cockcroft, met Frederick Lindemann and Baron Cherwell, who was a long-time scientific advisor to Winston Churchill. Cherwell dismissed CERN as another “European paper mill.” My father, usually composed, lost his temper and passionately defended the project. During the following visit to Harwell, Cockcroft reassured him that his reaction was appropriate. From that point on, the UK contributed to CERN, albeit initially as a series of donations rather than as the result of a formal commitment. It may be interesting to add that, during the same visit to London and Harwell, my father met the young John Adams and was so impressed that he immediately offered him a position at CERN.

What were the steps following the ratification of CERN’s convention?

Robert Valeur, chairman of the council during the interim period, and Ben Lockspeiser, chairman of the interim finance committee, used their authority to stir up early initiatives and create an atmosphere of confidence that attracted scientists from all over Europe. As Lew Kowarski noted, there was a sense of “moral commitment” to leave secure positions at home and embark on this new scientific endeavour.

During the interim period from May 1952 to September 1954, the council convened three sessions in Geneva whose primary focus was financial management. The organisation began with an initial endowment of approximately 1 million Swiss Francs, which – as I said – included a contribution from the UK known as the “observer’s gift”. At each subsequent session, the council increased its funding, reaching around 3.7 million Swiss Francs by the end of this period. When the permanent organisation was established, an initial sum of 4.1 million Swiss Francs was made available.

In 1954, my father was worried that if the parliaments didn’t approve the convention before winter, then construction would be delayed because of the wintertime. So he took a bold step and, with the approval of the council president, authorised the start of construction on the main site before the convention was fully ratified.

This led to Lockspeiser jokingly remarking later that council “has now to keep Amaldi out of jail”. The provisional council, set up in 1952, was dissolved when the European Organization for Nuclear Research officially came into being in 1954, though the acronym CERN (Conseil Européen pour la Recherche Nucléaire) was retained. By the conclusion of the interim period, CERN had grown significantly. A critical moment occurred on 29 September 1954, when a specific point in the ratification procedure was reached, rendering all assets temporarily ownerless. During this eight-day period, my father, serving as secretary general, was the sole owner on behalf of the newly forming permanent organisation. The interim phase concluded with the first meeting of the permanent council, marking the end of CERN’s formative years.

Did your father ever consider becoming CERN’s Director-General?

People asked him to be Director-General, but he declined for two reasons. First, he wanted to return to his students and his cosmic-ray research in Rome. Second, he didn’t want people to think he had done all this to secure a prominent position. He believed in the project for its own sake.

When the convention was finally ratified in 1954, the council offered the position of Director-General to Felix Bloch, a Swiss–American physicist and Nobel Prize winner for his work on nuclear magnetic resonance. Bloch accepted but insisted that my father serve as his deputy. My father, dedicated to CERN’s success, agreed to this despite his desire to return to Rome full time.

How did that arrangement work out?

My father agreed but Bloch wasn’t at that time rooted in Europe. He insisted on bringing all his instruments from Stanford so he could continue his research on nuclear magnetic resonance at CERN. He found it difficult to adapt to the demands of leading CERN and soon resigned. The council then elected Cornelis Jan Bakker, a Dutch physicist who had led the synchrocyclotron group, as the new Director-General. From the beginning, he was the person my father thought would have been the ideal director for the initial phase of CERN. Tragically though, Bakker died in a plane crash a year and a half later. I well remember how hard my father was hit by this loss.

How did the development of accelerators at CERN progress?

The decision to adopt the strong focusing principle for the Proton Synchrotron (PS) was a pivotal moment. In August 1952 Otto Dahl, leader of the Proton Synchrotron study group, Frank Goward and Rolf Widerøe visited Brookhaven just as Ernest Courant, Stanley Livingston and Hartland Snyder were developing this new principle. They were so excited by this development that they returned to CERN determined to incorporate it into the PS design. In 1953 Mervyn Hine, a long-time friend of John Adams with whom he had moved to CERN, studied potential issues with misalignment in strong focusing magnets, which led to further refinements in the design. Ultimately, the PS became operational before the comparable accelerator at Brookhaven, marking a significant achievement for European science.

It’s important here to recognise the crucial contributions of the engineers, who often don’t receive the same level of recognition as physicists. They are the ones who make the work of experimental physicists and theorists possible. “Viki” Weisskopf, Director-General of CERN from 1961 to 1965, compared the situation to the discovery of America. The machine builders are the captains and shipbuilders. The experimentalists are those fellows on the ships who sailed to the other side of the world and wrote down what they saw. The theoretical physicists are those who stayed behind in Madrid and told Columbus that he was going to land in India.

Your father also had a profound impact on the development of other Big Science organisations in Europe

Yes, in 1958 my father was instrumental, together with Pierre Auger, in the founding of the European Space Agency. In a letter written in 1958 to his friend Luigi Crocco, who was professor of jet propulsion in Princeton, he wrote that “it is now very much evident that this problem is not at the level of the single states like Italy, but mainly at the continental level. Therefore, if such an endeavour is to be pursued, it must be done on a European scale, as already done for the building of the large accelerators for which CERN was created… I think it is absolutely imperative for the future organisation to be neither military nor linked to any military organisation. It must be a purely scientific organisation, open – like CERN – to all forms of cooperation and outside the participating countries.” This document reflects my father’s vision of peaceful and non-military European science.

How is it possible for one person to contribute so profoundly to science and global collaboration?

My father’s ability to accept defeats and keep pushing forward was key to his success. He was an exceptional person with a clear vision and unwavering dedication. I hope that by sharing these stories, others might be inspired to pursue their goals with the same persistence and passion.

Could we argue that he was not only a visionary but also a relentless advocate?

He travelled extensively, talked to countless people, and was always cheerful and energetic. He accepted setbacks but kept moving forwards. In this connection, I want to mention Eliane Bertrand, later de Modzelewska, his secretary in Rome who later became secretary of the CERN Council for about 20 years, serving under several Director-Generals. She left a memoir about those early days, highlighting how my father was always travelling, talking and never stopping. It’s a valuable piece of history that, I think, should be published.

International collaboration has been a recurring theme in your own career. How do you view its importance today?

International collaboration is more critical than ever in today’s world. Science has always been a bridge between cultures and nations, and CERN’s history is a testimony of what this brings to humanity. It transcends political differences and fosters mutual understanding. I hope CERN and the broader scientific community will find ways to maintain these vital connections with all countries. I’ve always believed that fostering a collaborative and inclusive environment is one of the main goals of us scientists. It’s not just about achieving results but also about how we work together and support each other along the way.

Looking ahead, what are your thoughts on the future of CERN and particle physics?

I firmly believe that pursuing higher collision energies is essential. While the Large Hadron Collider has achieved remarkable successes, there’s still much we haven’t uncovered – especially regarding supersymmetry. Even though minimal supersymmetry does not apply, I remain convinced that supersymmetry might manifest in ways we haven’t yet understood. Exploring higher energies could reveal supersymmetric particles or other new phenomena.

Like most European physicists, I support the initiative of the Future Circular Collider and starting with an electron–positron collider phase so to explore new frontiers at two very different energy levels. However, if geopolitical shifts delay or complicate these plans, we should consider pushing hard on alternative strategies like developing the technologies for muon colliders.

Ugo Amaldi first arrived at CERN as a fellow in September 1961. Then, for 10 years at the ISS in Rome, he opened two new lines of research: quasi-free electron scattering on nuclei and atoms. Back at CERN, he developed the Roman pots experimental technique, was a co-discoverer of the rise of the proton–proton cross-section with energy, measured the polarisation of muons produced by neutrinos, proposed the concept of a superconducting electron–positron linear collider, and led LEP’s DELPHI Collaboration. Today, he advances the use of accelerators in cancer treatment as the founder of the TERA Foundation for hadron therapy and as president emeritus of the National Centre for Oncological Hadrontherapy (CNAO) in Pavia. He continues his mother and father’s legacy of authoring high-school physics textbooks used by millions of Italian pupils. His motto is: “Physics is beautiful and useful.”

This interview first appeared in the newsletter of CERN’s experimental physics department. It has been edited for concision.