by Trinh Xuan Thuan, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0 19 512917 2.

In a refreshing alternative to books that try to promote elegance, as opposed to correctness, as a reason to accept scientific theories, Trinh Xuan Thuan takes his readers on a fascinating romp through the world of modern physics. Starting with a discussion of truth and the elusive concept of beauty as opposed to elegance (a difference that he carefully explains), Thuan zeroes in on inevitability, simplicity and congruence as the key guiding notions in the search for the beautiful theories of nature. Much to his credit, he nevertheless makes it clear that, while truth is ultimately something that is decided by experiment, beauty is a subjective concept.

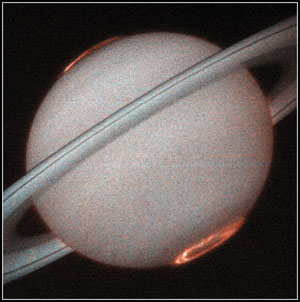

Although the subject matter of this book is deeply philosophical, it is discussed in wonderfully concrete terms. Rather than making vague statements about staggering cosmic or microcosmic magnitudes, Thuan offers hard facts (e.g. that the Sun turns 400 million tonnes of hydrogen into helium per second). A refreshingly down-to-earth follow-up to the esoteric discussion of truth and beauty is a description of the solar system, and the complex interplay between the strict laws of physics and plain random chance that gives rise to the world we so often take for granted.

In subsequent chapters Thuan describes chaos – with its range of applications from meteorology to medicine – and symmetry, emphasizing the symmetries between electricity and magnetism, and between space and time. A recurring theme in the book is the way in which seemingly opposing principles like these actually work together.

Moving on from classical mechanics and the need for both ordering and disordering principles in order to obtain structure, we meet quantum mechanics. A clear – if perhaps rather standard – introduction, with no mathematics, leads the reader to the inevitable conflict between that greatest of classical theories – Einstein’s General Theory of Relativity – and quantum mechanics. Here the author allows himself a few pages of deviation from the otherwise strict adherence to established fact that forms a great part of the book’s not inconsiderable charm.

A mercifully brief discussion of higher dimensional unification and string theory outlines the basic idea in a balanced way without any Bible-thumping. There’s little hope of steering clear of strings and other speculations these days, but the author makes a good job of maintaining a healthy perspective. The book could, in good faith, be recommended to the lay reader without fear that the line between established fact and interesting speculation be too blurred.

The last two chapters are delightful, and unusual in a book of this kind. The penultimate one invites the reader to think about the nature of life and the origins of its highly sophisticated and diverse structures – and to consider to what degree we can begin to understand these as coming from physics. Thuan discusses how one can find the appropriate level of description for the task, and suggests that we should hope not for detailed explanations of single phenomena but rather for an understanding of the global organizing principles that give rise to life and other complex structures.

The final chapter echoes Wigner’s famous concerns about what he called the “unreasonable effectiveness of mathematics” and asks why thought itself should be so effective – that is, why it is that we are able to make sense of anything, let alone the panoply of physics presented in the foregoing six chapters. Here the text takes an almost metaphysical turn, but, given the nature of the questions being asked, this is to be expected. While the practising scientist is unlikely to find much here that s/he hasn’t already thought about, the discussion is well suited to a layperson and offers quite a range of concepts to consider, from the idea of a Platonic world of mathematical forms, through the limits imposed by Gödel’s theorem, to the question of whether a God is needed, and the issue of why there should be such a thing as consciousness at all.

All in all, at a time when it is becoming increasingly difficult to find popular science books that are suitable for the intelligent non scientist, and that make clear distinctions between known fact and speculation, this book is a winner. The writing is graceful, smooth and rich in historical and cultural background, while at the same time keeping real physics close to the forefront. Perhaps most compelling is the book’s remarkable coherence. Topics flow easily and naturally into each other and one would be hard pressed to guess that it is a translation into English. Most people I know, practising physicists included, could learn something from this book, in addition to enjoying its style. To my high-energy physics colleagues: ask yourself how much you really know about the mechanisms involved in getting matter to clump together and make a planet. After all, there aren’t many of them in this solar system, are there? Get the book and have a look at Chapter 2!