When it comes online in 2030, the High-Luminosity LHC (HL-LHC) will feel like a new collider. The hearts of the ATLAS and CMS detectors, and 1.2 km of the 27 km-long Large Hadron Collider (LHC) ring will have been transplanted with cutting-edge technologies that will push searches for new physics into uncharted territory.

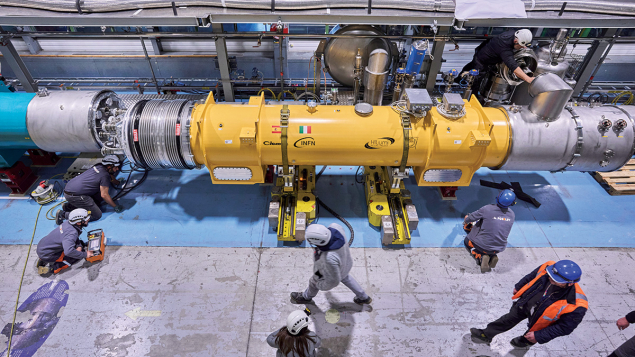

On the accelerator side, one of the most impactful upgrades will be the brand-new final focusing systems just before the proton or ion beams arrive at the interaction points. In the new “inner triplets”, particles will slalom in a more focused and compacted way than ever before towards collisions inside the detectors.

To achieve the required focusing strength, the new quadrupole magnets will use Nb3Sn conductors for the first time in an accelerator. Nb3Sn will allow fields as high as 11.5 T, compared to 8.5 T for the conventional NbTi bending magnets used elsewhere in the LHC. As they are a new technology, an integrated test stand of the full 60 m-long inner-triplet assembly is essential – and work is now in full swing.

Learning opportunity

“The main challenge at this stage is the interconnections between the magnets, particularly the interfaces between the magnets and the cryogenic line,” explains Marta Bajko, who leads work on the inner-triplet-string test facility. “During this process, we have encountered nonconformities, out-of-tolerance components, and other difficulties – expected challenges given that these connections are being made for the first time. This phase is a learning opportunity for everyone involved, allowing us to refine the installation process.”

The last magnet – one of two built in the US – is expected to be installed in May. Before then, the so-called N lines, which enable the electrical connections between the different magnets, will be pulled through the entire magnet chain to prepare for splicing the cables together. Individual system tests and short-circuit tests have already been successfully performed and a novel alignment system developed for the HL-LHC is being installed on each magnet. Mechanical transfer function measurements of some magnets are ongoing, while electrical integrity tests in a helium environment have been successfully completed, along with the pressure and leak test of the superconducting link.

“Training the teams is at the core of our focus, as this setup provides the most comprehensive and realistic mock-up before the installations are to be done in the tunnel,” says Bajko. “The surface installation, located in a closed and easily accessible building near the teams’ workshops and laboratories, offers an invaluable opportunity for them to learn how to perform their tasks effectively. This training often takes place alongside other teams, under real installation constraints, allowing them to gain hands-on experience in a controlled yet authentic environment.”

The inner triplet string is composed of a separation and recombination dipole, a corrector-package assembly and a quadrupole triplet. The dipole combines the two counter-rotating beams into a single channel; the corrector package fine-tunes beam parameters; and the quadrupole triplet focuses the beam onto the interaction point.

Quadrupole triplets have been a staple of accelerator physics since they were first implemented in the early 1950s at synchrotrons such as the Brookhaven Cosmotron and CERN’s Proton Synchrotron. Quadrupole magnets are like lenses that are convex (focusing) in one transverse plane and concave (defocusing) in the other, transporting charged particles like beams of light on an optician’s bench. In a quadrupole triplet, the focusing plane alternates with each quadrupole magnet. The effect is to precisely focus the particle beams onto tight spots within the LHC experiments, maximising the number of particles that interact, and increasing the statistical power available to experimental analyses.

Nb3Sn is strategically important because it lays the foundation for future high-energy colliders

Though quadrupole triplets are a time-honoured technique, Nb3Sn brings new challenges. The HL-LHC magnets are the first accelerator magnets to be built at lengths of up to 7 m, and the technical teams at CERN and in the US collaboration – each of which is responsible for half the total “cold mass” production – have decided to produce two variants, primarily driven by differences in available production and testing infrastructure.

Since 2011, engineers and accelerator physicists have been hard at work designing and testing the new magnets and their associated powering, vacuum, alignment, cryogenic, cooling and protection systems. Each component of the HL-LHC will be individually tested before installation in the LHC tunnel, however, this is only half the story as all components must be integrated and operated within the machine, where they will all share a common electrical and cooling circuit. Throughout the rest of 2025, the inner-triplet string will test the integration of all these components, evaluating them in terms of their collective behaviour, in preparation for hardware commissioning and nominal operation.

“We aim to replicate the operational processes of the inner-triplet string using the same tools planned for the HL-LHC machine,” says Bajko. “The control systems and software packages are in an advanced stage of development, prepared through extensive collaboration across CERN, involving three departments and nine equipment groups. The inner-triplet-string team is coordinating these efforts and testing them as if operating from the control room – launching tests in short-circuit mode and verifying system performance to provide feedback to the technical teams and software developers. The test programme has been integrated into a sequencer, and testing procedures are being approved by the relevant stakeholders.”

Return on investment

While Nb3Sn offers significant advantages over NbTi, manufacturing magnets with it presents several challenges. It requires high-temperature heat treatment after winding, and is brittle and fragile, making it more difficult to handle than the ductile NbTi. As the HL-LHC Nb3Sn magnets operate at higher current and energy densities, quench protection is more challenging, and the possibility of a sudden loss of superconductivity requires a faster and more robust protection system.

The R&D required to meet these challenges will provide returns long into the future, says Susana Izquierdo Bermudez, who is responsible at CERN for the new HL-LHC magnets.

“CERN’s investment in R&D for Nb3Sn is strategically important because it lays the foundation for future high-energy colliders. Its increased field strength is crucial for enabling more powerful focusing and bending magnets, allowing for higher beam energies and more compact accelerator designs. This R&D also strengthens CERN’s expertise in advanced superconducting materials and technology, benefitting applications in medical imaging, energy systems and industrial technologies.”

The inner-triplet string will remain an installation on the surface at CERN and is expected to operate until early 2027. Four identical assemblies will be installed underground in the LHC tunnel from 2028 to 2029, during Long Shutdown 3. They will be located 20 m away on either side of the ATLAS and CMS interaction points.