Helgoland, by Carlo Rovelli, Allen Lane

It is often said that “nobody understands quantum mechanics” – a phrase usually attributed to Richard Feynman. This statement may, however, be misleading to the uninitiated. There is certainly a high level of understanding of quantum mechanics. The point, moreover, is that there is more than one way to understand the theory, and each of these ways requires us to make some disturbing concessions.

Carlo Rovelli’s Helgoland is therefore a welcome popular book – a well-written and easy-to-follow exploration of quantum mechanics and its interpretation. Rovelli is a theorist working mainly on quantum gravity and foundational aspects of physics. He is also a very successful popular author, distinguished by his erudition and his ability to illuminate the bigger picture. His latest book is no exception.

Helgoland is a barren German island of the North Sea where Heisenberg co-invented quantum mechanics in 1925 while on vacation. The extraordinary sequence of events between 1925 and 1926, when Heisenberg, Jordan, Born, Pauli, Dirac and Schrödinger formulated quantum mechanics, is the topic of the opening chapter of the book.

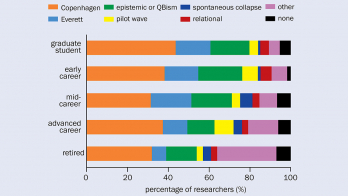

Rovelli only devotes a short chapter to discuss interpretations in general. This is certainly understandable, since the author’s main target is to discuss his own brainchild: relational quantum mechanics. This approach, however, does not do justice to popular ideas among experts, such as the many-worlds interpretation. The reader may be surprised not to find anything about the Copenhagen (or, more appropriately, Bohr’s) interpretation. This is for very good reason, however, since it is not generally considered to be a coherent interpretation. Having mostly historical significance, it has served as inspiration to approaches that keep the spirit of Bohr’s ideas, like consistent histories (not mentioned in the book at all), or Rovelli’s relational quantum mechanics.

Relational quantum mechanics was introduced by Rovelli in an original technical article in 1996 (Int. J. Theor. Phys. 35 1637). Helgoland presents a simplified version of these ideas, explained in more detail in Rovelli’s article, and in a way suitable for a more general audience. The original article, however, can serve as very nice complementary reading for those with some physics background. Relational quantum mechanics claims to be compatible with several of Bohr’s ideas. In some ways it goes back to the original ideas of Heisenberg by formulating the theory without a reference to a wavefunction. The properties of a system are defined only when the system interacts with another system. There is no distinction between observer and observed system. Rovelli meticulously embeds these ideas in a more general historical and philosophical context, which he presents in a captivating manner. He even speculates whether this way of thinking can help us understand topics that, in his opinion, are unrelated to quantum mechanics, such as consciousness.

Helgoland’s potential audience is very diverse and manages to transcend the fact that it is written for the general public. Professionals from both the sciences and the humanities will certainly learn something, especially if they are not acquainted with the nuances of the interpretations of modern physics. The book, however, as is explicitly stated by Rovelli, takes a partisan stance, aiming to promote relational quantum mechanics. As such, it may give a somewhat skewed view of the topic. In that respect, it would be a good idea to read it alongside books with different perspectives, such as Sean Carroll’s Something Deeply Hidden (2019) and Adam Becker’s What is Real? (2018).