Data from the ATLAS experiment is a key element in HALO, an important new commission undertaken for Art Basel, the world’s premier fair for contemporary art. It’s the latest exciting outcome of Arts at CERN, which has become a major player in the world where art and science meet.

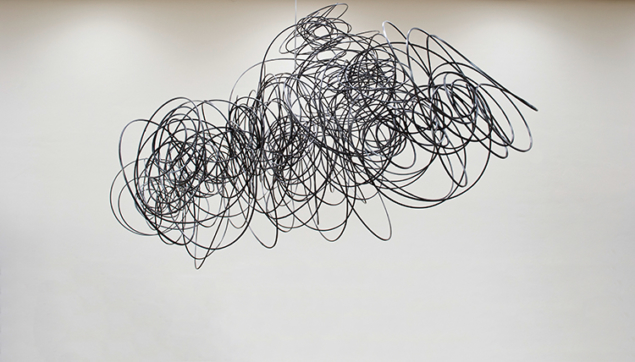

Lift up your eyes as you walk through the principal entrance to CERN’s main building and you will see a tangled iron coil suspended above the central staircase. Rather like electron orbitals marking out the shape of an atom, the structure’s overlapping lines form hints of something more tangible that changes as you move – a human body. Here, in his sculpture Feeling Material XXXIV, the artist Antony Gormley has spun a chaotic spiralling line that envelopes the body’s space.

Artists, like scientists, have always been keen observers of the world about them and Gormley is no exception. It was his interest in how spaces are delineated that led to his first contacts with CERN physicist Michael Doser in 2006, and ultimately to his donation of Feeling Material XXXIV to the Organization in 2008. Over the years many artists have visited CERN, intrigued by its research; the American performance artist James Lee Byars even featured on the cover of CERN Courier in September 1972. And in the 1990s, British artist and film-maker Ken McMullen visited the laboratory as a result of his friendship with the daughter of the late Maurice Jacob, a well-known CERN theorist. The visit sowed the seeds for a major project, Signatures of the Invisible, based on a collaboration between the London Institute and CERN. This project brought 11 established artists from various countries, including McMullen, to work with scientists and technicians at CERN during 1999–2000, resulting in works of art that were exhibited worldwide (CERN Courier May 2001 p23).

The experience proved rewarding for both sides. Writing in the Courier (July 2001, p30), Ian Sexton, the CERN technician who worked with laser cutting and other techniques on McMullen’s piece Crumpled Theory, described his pleasure at seeing the artist’s first sight of the completed work “simply presented on the workshop floor, with sunlight streaming through the blinds. Ken was … delighted. His enthusiasm was a most unusual experience for me. Normally on completion of a job at CERN a perfunctory ‘thank you’ is the only response.”

The project had involved a significant commitment by CERN. The Press Office managed the project on the Organization’s behalf, a number of scientists became deeply involved, and the artists were offered the use of the laboratory’s workshop – all of which implied a great deal of disruption and additional work for those concerned. So perhaps there were reservations in the minds of some at CERN when a new “science and art” initiative began to take shape. In 2009, creative producer Ariane Koek decided to use the award of a Clore Fellowship to come to CERN and – with the encouragement of the Director-General at the time, Rolf Heuer – work out how to establish and fund an artists’ residency scheme. Heuer was suitably impressed by her proposals and the following year, after a selection process, Koek was taken on to set up Arts at CERN.

Cultural policy

These efforts bore fruit in August 2011 with the launch of CERN’s first-ever cultural policy. Its central element is a selection process for arts engagement with CERN, with a cultural board for the arts to advise on projects and collaborations involving CERN. The initiative brought order and direction to what had been an ad-hoc approach to CERN’s involvement with the arts.

The first outwardly visible outcome of Arts at CERN was a competition, Collide at CERN, announced in 2011 and open to artists from anywhere in the world. A key element was to pair winning artists with scientists at CERN during a residency lasting up to three months. One strand in this award – the Prix Electronica Collide @ CERN prize for Digital Arts – was set up in collaboration with Austria-based digital arts organisation Ars Electronica, and the residency consisted of two months at CERN and one month at Ars Electronica’s research and development lab. The second strand – Collide @ CERN Geneva – marked a partnership with the City and Canton of Geneva, and in the first year was for dance and performance.

The partnership with Ars Electronica was a coup for CERN and the new cultural policy. Over 40 years, Ars Electronica had built up a formidable reputation in bringing artists, scientists and engineers together. Widely publicised by CERN, the partnership was well received in the arts world, but it was perhaps not so well understood at CERN. Was this something that CERN should be doing and who was paying for it all?

Heuer, who was instrumental in initiating Arts at CERN, was always clear on the first point. “The arts and science are inextricably linked; both are ways of exploring our existence, what it is to be human and what is our place in the universe,” he said on launching the cultural policy. Commenting later after three years of successful partnership with Ars Electronica, he wrote: “The level of heated debate about the so-called two-cultures is a constant source of bafflement to me. Of course arts and science are linked. Both are about creativity. Both require technical mastery. And both are about exploring the limits of human potential.”

Regarding the second point, Arts at CERN was conceived from the start to be mainly self-funding. Support from CERN initially came through its programmes for fellows and students. Funding for the original Collide at CERN programme came from Ars Electronica, the City and the Canton of Geneva, and individual private donors, as well as from the UNIQA Insurance Group, which has a long association with CERN and continues to sponsor the Collide programme. Currently, FACT (Foundation for Art and Creative Technology), based in Liverpool in the UK, is the main partner for the Collide International award, while the Republic and Canton of Geneva and the City of Geneva support the Collide Geneva strand. Collide Geneva is now awarded in alternate years with Collide Pro Helvetia, in which artists from across Switzerland can compete for a residency funded principally by Pro Helvetia, the Swiss Arts Council. In addition, via a slightly different scheme called Accelerate, each year ministries or foundations in two different countries fund two artists working in different domains to come to CERN for one month. A further essential strand that has existed from the beginning brings many more artists to the Laboratory. Originally named Visiting Artists, now called Guest Artists, it hosts up to 10 artists a year who are specially selected for a visit of one to two days which they fund themselves. Together these three strands form the Arts at CERN programme.

A new era begins

By autumn 2014, when the call went out for a new person to head Arts at CERN, the programme had already earned a global reputation. Two internationally known artists and recipients of the Collide International award epitomise this reach: Bill Fontana and Ryoji Ikeda. Sound-sculptor Fontana, from the US, had produced works based on sounds across the globe when he was awarded the 2013 international residency. He explored sounds recorded in the LHC tunnel in works such as Acoustic Time Travel (CERN Courier December 2012 p32), and was followed a year later by Ikeda, Japan’s leading electronic composer and visual artist, who used his residency to inform his works supersymmetry and micro|macro.

This growing reputation within the science and art scene appealed in particular to the art historian and curator Mónica Bello, who had more than 15 years’ experience in curating and managing cultural programmes in art, science and technology institutions in different countries and had spent five years as artistic director of the VIDA International Art and Artificial Life Awards. Educated in modern and contemporary art history, she had been exposed to new ideas emerging at the boundaries of modern art and become passionate about the fusion between science and art. “I like art that is based on open processes, where different agents – the artists, researchers, even the audience – can join together to become the project,” she explains. “Experimentation with openness is the most exciting thing that’s happening in the arts right now – and CERN is the place to be for that.”

Bello took up her position at CERN in March 2015, joining co-ordinator Julian Caló. In accelerator terms, by the following year, Arts at CERN was already running at its design energy and beyond. The programme was bringing artists to the laboratory for as many as four residencies a year, and the number of entries for the Collide International award had risen from some 400 when it was launched in 2011 to around 1000.

Bello’s main vision is to move the main focus beyond exploration and artistic research towards the further development of new art commissions and exhibitions. Continuing to support the artists once they finish their residencies at CERN is essential for this, and one way is to connect the artists with CERN scientists that have links to the cities of the programmes’ partners. This was initiated with Liverpool, where artists spent a one-month residency at FACT after being at CERN and where they were connected with research groups at Liverpool University led by LHCb physicist Tara Shears. Connecting CERN to international cultural organisations is part of the same objective, through links formed with different cities and countries.

These new developments are fully supported by CERN’s current management. Earlier this year, Director-General Fabiola Gianotti made her views on the “two cultures” clear at the World Economic Forum in Davos: “Too often people put science and humanities, or science and the arts, in different compartments… but they do have much in common. They are the highest expression of the creativity and the curiosity of humanity. We should really talk about culture in general, and not focus on one particular sector of culture. This is an important message we should be giving to teachers and to young people, for a better world, so they can grow to face the challenges of society.”

Arts at CERN currently has a clear home within CERN’s international relations sector. The aim is to provide stability for the programme, with a view to making it self-sustaining with separate funding within the context of the CERN & Society Foundation. At the same time, Arts at CERN forms part of a broader interest at CERN in the arts, which includes a distinctive and complementary programme Arts@CMS. This education and outreach initiative of the CMS collaboration has set up school-based projects and collaborations with artists with the aim of inspiring a greater appreciation of CERN’s science within the public at large.

A new production scheme

Arts at CERN has clearly been a resounding success with the arts community, and reaching audiences beyond the confines of the laboratory has proved no problem at all. Nor has it been difficult to find scientists willing to work with the artists; more than 200 have so far been involved. But it is by no means easy to mount an exhibition at a scientific laboratory – in places almost an industrial site – where health and safety are of paramount importance. There have been some obvious artistic interventions, such as when choreographer Gilles Jobin, winner of the 2012 Collide Geneva award, installed dancers in the CERN restaurant and computer centre, and even the library; and his project Quantum – a fusion of dance and lighting installation developed with Julius von Bismarck, the first Collide International artist-in-residence – debuted in the CMS cavern during CERN’s open days in 2013, before embarking on an international tour (CERN Courier November 2013 p29).

More recently, as part of Geneva’s annual Electron Festival in 2016, the winners of the 2014 Collide Geneva award, Rudy Decelière and Vincent Hänni, showed work developed with experimentalist Robert Kieffer and theorist Diego Blas. Their sound installation Horizons Irrésolus (2016) – which consists of 888 micro-synthesisers and speakers, network cable and nylon thread – was installed at CERN for visits during the Easter weekend when the festival traditionally takes place. The effort required by many people at CERN included registration to allow access to the Meyrin site and a shuttle bus to take visitors to see the installation. The response was enthusiastic, but not large.

It is to address such problems that Bello is developing the production and exhibition stages of the residencies. Rather as a scientific experiment evolves from conception to data-collection, analysis and publication, so does an artistic endeavour evolve from exploration to production and exhibition. The original focus of the residencies at CERN was on exploration: having artists and scientists come together to evolve ideas. In the new phase for Arts at CERN, at the end of their residencies, artists will be invited to propose a work to be considered for additional funding for production. The aim is to collaborate with other institutes to co-produce cultural works for ideas that are worth developing, and to curate the resulting work so that it can be shown and shared with the CERN community.

In 2016 CERN began a new collaboration for the Collide International award involving FACT, ushering in the production phase. To support production of the artworks, CERN and FACT have brought together several important European cultural organisations under the umbrella of ScANNER (Science and Art Network for New Exhibitions and Research). Supported by ScANNER, a major exhibition will open at FACT in November 2018 showcasing artworks from, among others, the 2018 Collide International award winner and four previous winners:

Semiconductor (2015), Yunchul Kim (2016), studio hrm199 led by Haroon Mirza (2017) and Suzanne Triester (2018). The exhibition will then tour all venues of the ScANNER members during 2019 and 2020.

Meanwhile, Arts at CERN continues to be a major influence across an impressive range of artistic areas. For example, in her project Quantum Nuggets, designer Laura Couto (Collide Pro Helvetia award 2017) has developed a computer program to enable other artists and designers to produce 3D shapes based on collision data from the LHC, thus creating real objects, such as furniture, that echo the invisible quantum world of particle physics. And in February this year Cheolwon Chang (Accelerate Korea) spent time at CERN finding out about the geometric properties of nature and how mathematics influences our further understanding of the universe. The winners of two awards for 2018 were announced in March: Suzanne Treister (Collide International) and Anne Sylvie Henchoz and Julie Lang (Collide Geneva).

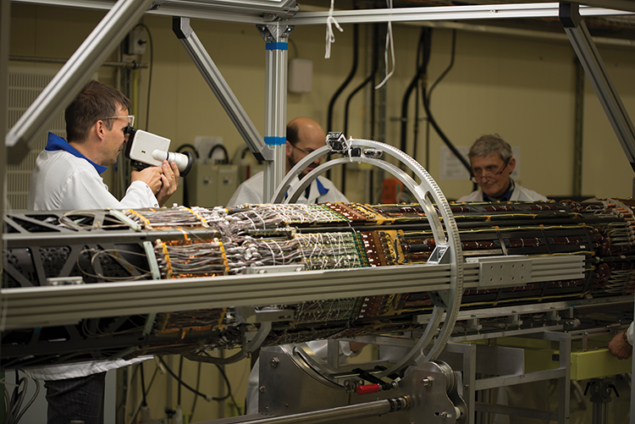

Most recently, a prestigious commission for Art Basel held on 11–17 June and guest-curated by Bello, has highlighted the pinnacles that Arts at CERN is reaching. Swiss watchmakers, Audemars Piguet, a partner of Art Basel, chose the British artist-duo Semiconductor to create the Audemars Piguet Art Commission for the 2018 fair. Ruth Jarman and Joe Gerhardt, who work together under the name Semiconductor, were the recipients of the 2015 Collide International award and for Art Basel they created HALO – an installation that surrounds visitors with data collected by the ATLAS experiment at the LHC. HALO consists of a 10 m-wide cylinder defined by vertical piano wires, within which a 4 m-tall screen displays particle collisions. The data also trigger hammers that strike the wires and set up vibrations to create a multisensory experience.

This important commission is testament to the impact that the Arts at CERN programme is having in the world of contemporary art, and underlines its importance in bringing together apparently disparate ways in viewing and making sense of the world, the universe in which we live. There are many people who say they do not appreciate modern art, just as there are many who say that they never liked physics. But with modern art, just as with modern physics, making a little effort can open up remarkable new ways of thinking about our place in space and time. Arts at CERN is very clearly bringing people together in ways that open their minds and allow them not necessarily to understand but to appreciate how others view the world about us.

- This article was modified on 5 September 2018.

Further reading

For more about the first years of the Arts at CERN programme, see “In/visible: the inside story of the making of Arts at CERN”, Ariane Koek, Interdisciplinary Science Reviews 42 345.