Breaking with decades of haloscope design, the ALPHA and MADMAX collaborations are pushing the search for dark matter into a promising new niche.

One hundred µeV. 25 GHz. 10 m. This is the mass, frequency and de Broglie wavelength of a typical post-inflation axion. Though well motivated as a potential explanation for both the nature of dark matter and the absence of CP violation in the strong interaction, such axions subvert the “particle gas” picture of dark matter familiar to many high-energy physicists, and pose distinct challenges for experimentalists.

Axions could occupy countless orders of magnitude in mass, but those that result from symmetry breaking after cosmic inflation are a particularly interesting target, as their mass is predicted to lie within a narrow window of just one or two orders of magnitude, up to and around 100 µeV (see “Introducing the axion”). Assuming a mass of 100 µeV and a local dark-matter density of 0.4 GeV/cm3 in the Milky Way’s dark-matter halo, a back-of-the-envelope calculation indicates that every cubic de Broglie wavelength should contain more than 1021 axions. Such a high occupation number means that axion dark matter would act like a classical field. Moving through the Earth at several hundreds of kilometres per second, the Milky Way’s axion halo would be nonrelativistic and phase coherent over domains metres in width and tens of microseconds in duration.

Axion haloscopes seek to detect this halo via faint electric-field oscillations. The same couplings that should allow axions to decay to pairs of photons on timescales many orders of magnitude longer than the age of the universe should allow them to “mix” with photons in a strong magnetic field. The magnetic field provides a virtual photon, and the axion oscillates into a real photon. For several decades, the primary detection strategy has been to seek to detect their resonant conversion into an RF signal in a microwave cavity permeated by a magnetic field. The experiment is like a car radio. The cavity is tuned very slowly. At the frequency corresponding to the cosmic axion’s mass, a faint signal would be amplified.

The ADMX, CAPP and HAYSTAC experiments have led the search below 25 μeV. These searches are dauntingly difficult, requiring the whole experiment to be cooled down to around 100 mK. Quantum amplifiers must be able to read out signals as weak as 10–24 W. The current generation of experiments can tune over about 10% of the resonant frequency, remaining stable at each small frequency step for 15 minutes before moving onto the next frequency. The steps are determined by the expected lineshape of the axion signal. Axion velocities in the Milky Way’s dark-matter halo should follow a thermal distribution set by the galaxy’s gravitational potential. This produces a spread of kinetic energies that broadens the corresponding photon frequency spectrum into a boosted-Maxwellian shape with a width about 10–6 of the frequency. For a mass around 100 μeV, the expected width is about 25 kHz.

The trouble is that the resonance frequency of a cavity is set by its diameter: the larger the cavity, the smaller the accessible frequency. Because the signal power scales with the cavity volume, it is increasingly difficult to achieve a good sensitivity at higher masses. For a 100 µeV axion with frequency 25 GHz that oscillates into a 25 GHz photon, the cavity would have to be of order only a centimetre wide.

Probing this parameter space calls for novel detector concepts that decouple the mass of the axion from the volume where axions convert into radio photons. This realisation has motivated a new generation of haloscopes built around electromagnetic structures that no longer rely on the resonant frequency of a closed cavity, but instead engineer large effective volumes matched to high axion masses.

Two complementary approaches – dielectric haloscopes and plasma haloscopes – exploit this idea in different ways. Each offers the possibility of discovering a post-inflation axion in the coming decade.

The MADMAX dielectric haloscope

Thanks to their electromagnetic coupling, a galactic halo of axions would drive a spatially uniform electric field oscillation parallel to an external magnetic field. For 100 µeV axions, it would oscillate at about 25 GHz. In such a field, a dielectric disc will emit photons perpendicular to its surfaces due to an electromagnetic boundary effect: the discontinuity in permittivity forces the axion-induced field to readjust, producing outgoing microwaves.

The Magnetized Disc and Mirror Axion (MADMAX) collaboration seeks to boost this signal through constructive interference. The trick is multiple discs, with tuneable spacing and a mirror to reflect the photons. As the axion halo would be a classical field, each disc should continuously emit radiation in both directions. For multiple dielectric discs, coherent radiation from all disc surfaces leads to constructive interference when the distance between the discs is about half the electromagnetic wavelength, potentially boosting axion-to-photon conversion in a broad frequency range. The experiment can be tuned for a given axion mass by controlling the spacing between the discs with micron-level precision. Arbitrarily many discs can be incorporated, thereby decoupling the volume where axions can convert into photons from the axion’s mass.

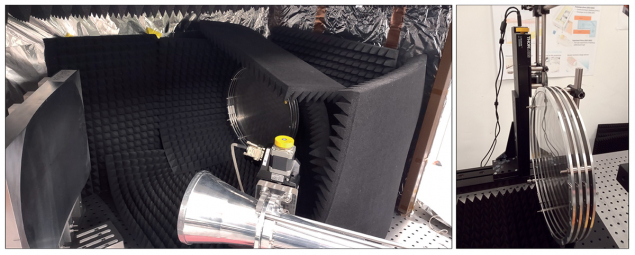

The MADMAX collaboration has developed two indirect techniques to measure the “boost factor” of its dielectric haloscopes. In the first method, scanning a bead along the volume maps the three-dimensional induced electric field, from which the boost factor is then computed as the integral of the electric field over the sensitive volume. This method yielded 15% uncertainty for a prototype booster with a mirror and three 30 cm-diameter sapphire discs (see “A work in progress” figure). By studying the response of the prototype in the absence of an external magnetic field, the collaboration set the world’s best limits on dark-photon dark matter in the mass range from 78.62 to 83.95 μeV.

The MADMAX collaboration has developed two indirect techniques to measure the “boost factor” of its dielectric haloscopes

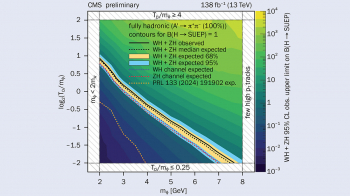

The boost factor can alternatively be obtained by modelling the booster’s response using physical properties extracted from reflectivity measurements and the behaviour of the power spectrum in the given frequency range. This method was applied to MADMAX prototypes inside the world’s largest warm-bore superconducting dipole magnet. Named after the Italian physicist who designed it in the 1970s, the Morpurgo magnet is normally used to test subdetectors of the ATLAS experiment using beams from CERN’s North Area. Since MADMAX requires no beam, a first axion search using the diameter aperture took place during the 2024 winter shutdown of the LHC. The prototype booster included a 20 cm-diameter mirror and three sapphire discs separated by aluminium rings. Frequencies around 19 GHz were explored by adjusting the mirror position. No significant excess consistent with an axion signal was observed. Despite coming from a small prototype, these results surpass astrophysical bounds and constraints from the CERN Axion Solar Telescope (CAST), demonstrating the detection power of dielectric haloscopes.

As a next step, a prototype booster with a mirror and up to twenty 30 cm-diameter discs is expected to deliver a factor 10 to 100 improvement over the 2024 tests. The positions of its discs will be adjusted inside its stainless-steel cryostat using cryogenic piezo motors. The setup is currently being commissioned and is set for installation in the Morpurgo magnet during the third long shutdown of the LHC from mid-2026 to 2029. An important goal is to prove the broad-band scanning capacity of dielectric haloscopes at cryogenic temperatures and conditions close to those of the final MADMAX design. Operating at 4 K will enhance MADMAX’s sensitivity by reducing noise from thermal radiation. A prototype has already been successfully tested inside a custom-made glass fibre cryostat in the Morpurgo magnet in cooperation with CERN’s cryogenic laboratory.

The final baseline detector foresees a 9 T superconducting dipole magnet with a warm bore of about 1.3 m. A first design has been developed and important aspects of its technological feasibility have already been tested, such as quench protection and conductor performance. As a first step, an intermediate 4 T warm-bore magnet is being purchased. It should be available around 2030. Once constructed, the magnet will be installed at DESY’s axion platform inside the former HERA H1 iron yoke, where preparations for the required cryogenic infrastructure are underway.

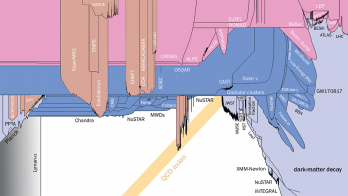

With MADMAX’s prototype booster scaling towards its final size, and quantum detection techniques such as travelling-wave parametric amplifiers and single-photon detectors being developed, significant improvements in sensitivity are on the horizon for dielectric haloscopes. MADMAX is on a promising path to probing axion dark matter in the 40 to 400 µeV mass range at sensitivities sufficient to discover axion dark matter at the classic Dine–Fischler–Srednicki–Zhitnitsky (DFSZ) and Kim–Shifman–Vainshtein–Zakharov (KSVZ) theory benchmarks.

The ALPHA plasma haloscope

In a plasma, photons acquire an effective mass determined by the plasma frequency, which depends on the density of charge carriers. If the plasma frequency is close to the axion’s Compton frequency, axion–photon mixing is resonantly enhanced. As the plasma could in principle be of any volume, the volume in which the axion field converts into photons has been decoupled from the axion mass – but tuning the plasma frequency is not feasible, preventing a detector based on this effect from scanning a wide range of masses.

In 2019, Matthew Lawson, Alexander Millar, Matteo Pancaldi, Edoardo Vitagliano and Frank Wilczek proposed performing this experiment using a metamaterial plasma with a tunable electromagnetic dispersion which mimics that of a real plasma. In a plasma haloscope, this metamaterial is a lattice of thin metallic wires embedded in vacuum. By adjusting the wire spacing, the diameter of the wires and their arrangement, the resonant plasma frequency can be tuned over a wide range.

The ALPHA collaboration was formed in 2021 to build a full-scale plasma haloscope capable of probing axion masses from 40 to 400 μeV, corresponding to axion frequencies from 10 to 100 GHz. While challenges related to detecting an extremely feeble signal remain, the simplicity of the cavity design, particularly in the magnet geometry and the tuning mechanism, offers flexibility.

ALPHA’s design can be pictured as a large-bore superconducting solenoid magnet, and a resonator housing an array of thin copper or superconducting wires stretched along the field direction. Photons are extracted through waveguides and fed into an ultra-low-noise microwave receiver chain, cooled by a dilution refrigerator to below 100 mK, developing quantum-sensing techniques developed in close collaboration with the HAYSTAC collaboration. Photons are amplified with Josephson parametric amplifiers – the same technique used for qubits used in quantum computers, and the topic of the 2025 Nobel Prize in Physics awarded to John Clarke, Michel Devoret and John Martinis. Tests at room temperature in 2022 and 2023 demonstrated that the response of the meta-plasma can be tuned across the 10 to 20 GHz range with a modest number of configuration changes, and that the quality factors exceed 104 even before cooling down to cryogenic temperatures.

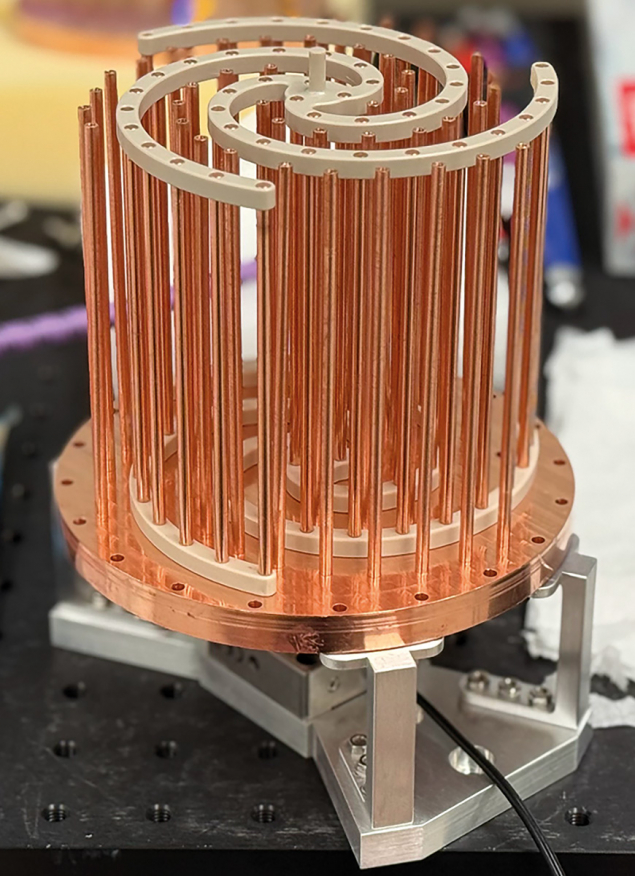

Two designs are being pursued to design a tuning mechanism that allows precise adjustment of the plasma frequency with minimal mechanical intervention: a spiral design where a single rotating rod tunes a set of three spiral arms relative to another set of fixed spiral arms (see “Plasma tuning” figure); and a design with multiple spinners rotating groups of wires relative to a fixed grid of wires.

It is an exciting time for axion searches

ALPHA’s development plan proceeds in two main stages. Phase I is currently being constructed at Yale University’s Wright Laboratory, and focuses on employing established technology to demonstrate the technique and search for axions with masses from 40 to 80 μeV. Phase I’s cavity, consisting of copper plasma resonators, will be immersed in a 9 T magnet, 17.5 cm in diameter and 50 cm tall. The expected conversion power in ALPHA’s frequency range is of order 10–24 W – comparable to the thermal noise in a 50 Ω resistor cooled to 50 mK. The read-out chain therefore employs Josephson parametric amplifiers whose noise temperatures approach the standard quantum limit. The system is designed to scan continuously while maintaining sensitivity close to the KSVZ axion-photon coupling, a benchmark for well-motivated axion models. The data-acquisition strategy builds on techniques developed in ADMX and HAYSTAC: fast Fourier transforms of the time-stream, coherent stacking across overlapping frequency bins and real-time evaluation of excess-power statistics.

Several improvements are being developed in parallel for Phase II. Quantum sensing techniques have the potential to boost the signal while reducing noise. Such techniques include HAYSTAC-style noise squeezing, using cavity entanglement and state swapping to enhance the signal, and single-photon detection. Dramatically increasing the quality factor of superconducting plasma resonators will also significantly boost the signal. Last but not least, magnets with a larger bore and higher field, such as the ones being deployed at the neutron scattering facilities at Oak Ridge National Laboratory, are expected to expand the experimental reach up to 200 μeV and push the sensitivity to below the axion–photon coupling of the DFSZ model, another classic theoretical benchmark.

Beginning in 2026, ALPHA Phase I will start taking its first physics data, initially searching for dark photons – a dark-matter candidate that interacts with plasma without requiring the presence of a magnetic field. After commissioning ALPHA’s magnet, a full axion search will commence during 2027 and 2028.

It is an exciting time for axion searches. New experiments are coming online, implementing new ideas to expand the accessible mass ranges. Groups in Italy, Japan and Korea are exploring alternative metamaterial geometries, including superconducting wire meshes and photonic crystals that replicate plasma behaviour at higher frequencies. European teams linked to the IAXO collaboration are considering hybrid systems that couple plasma-like resonators to strong dipole magnets. ALPHA will search for axions in the well-motivated region, first focusing between 40 and 80 μeV, and then between 80 and 200 μeV.

Intense efforts are underway. Discoveries may be just around the corner.

Further reading

MADMAX Collab 2025 Phys. Rev. Lett. 135 041001.

A Millar et al. 2023 Phys. Rev. D 107 055013.