Angelica Facoetti explains five facts accelerator physicists need to know about radiobiology to work at the cutting edge of particle therapy.

In 1895, mere months after Wilhelm Röntgen discovered X-rays, doctors explored their ability to treat superficial tumours. Today, the X-rays are generated by electron linacs rather than vacuum tubes, but the principle is the same, and radiotherapy is part of most cancer treatment programmes.

Charged hadrons offer distinct advantages. Though they are more challenging to manipulate in a clinical environment, protons and heavy ions deposit most of their energy just before they stop, at the so-called Bragg peak, allowing medical physicists to spare healthy tissue and target cancer cells precisely. Particle therapy has been an effective component of the most advanced cancer therapies for nearly 80 years, since it was proposed by Robert R Wilson in 1946.

With the incidence of cancer rising across the world, research into particle therapy is more valuable than ever to human wellbeing – and the science isn’t slowing down. Today, progress requires adapting accelerator physics to the demands of the burgeoning field of radiobiology. This is the scientific basis for developing and validating a whole new generation of treatment modalities, from FLASH therapy to combining particle therapy with immunotherapy.

Here are the top five facts accelerator physicists need to know about biology at the Bragg peak.

1. 100 keV/μm optimises damage to DNA

Almost every cell’s control centre is contained within its nucleus, which houses DNA – your body’s genetic instruction manual. If the cell’s DNA becomes compromised, it can mutate and lose control of its basic functions, leading the cell to die or multiply uncontrollably. The latter results in cancer.

For more than a century, radiation doses have been effective in halting the uncontrollable growth of cancerous cells. Today, the key insight from radiobiology is that for the same radiation dose, biological effects such as cell death, genetic instability and tissue toxicity differ significantly based on both beam parameters and the tissue being targeted.

Biologists have discovered that a “linear energy transfer” of roughly 100 keV/μm produces the most significant biological effect. At this density of ionisation, the distance between energy deposition events is roughly equal to the diameter of the DNA double helix, creating complex, repair-resistant DNA lesions that strongly reduce cell survival. Beyond 100 keV/μm, energy is wasted.

DNA is the main target of radiotherapy because it holds the genetic information essential for the cell’s survival and proliferation. Made up of a double helix that looks like a twisted ladder, DNA consists of two strands of nucleotides held together by hydrogen bonds. The sequence of these nucleotides forms the cell’s unique genetic code. A poorly repaired lesion on this ladder leaves a permanent mark on the genome.

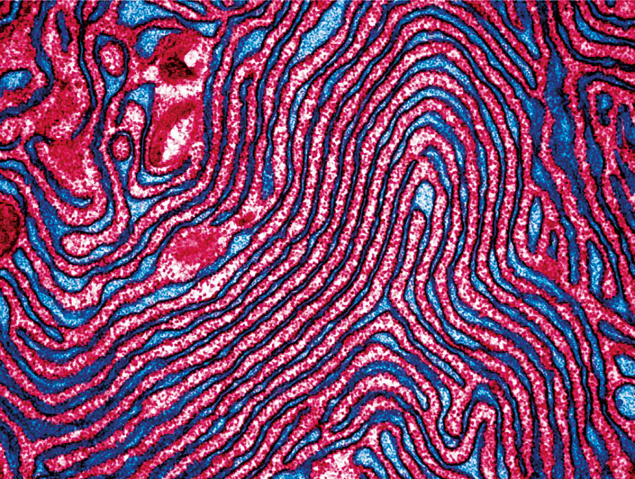

When radiation induces a double-strand break, repair is primarily attempted through two pathways: either by rejoining the broken ends of the DNA, or by replacing the break with an identical copy of healthy DNA (see “Repair shop” image). The efficiency of these repairs decreases dramatically when the breaks occur in close spatial proximity or if they are chemically complex. Such scenarios frequently result in lethal mis-repair events or severe alterations in the genetic code, ultimately compromising cell survival.

This fundamental aspect of radiobiology strongly motivates the use of particle therapy over conventional radiotherapy. Whereas X-rays deliver less than 10 keV/μm, creating sparse ionisation events, protons deposit tens of keV/μm near the Bragg peak, and heavy ions 100 keV/μm or more.

2. Mitochondria and membranes matter too

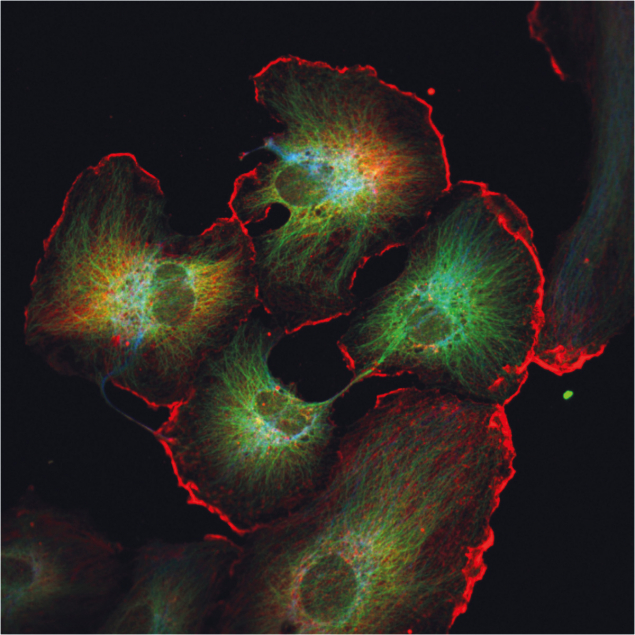

For decades, radiobiology revolved around studying damage to DNA in cell nuclei. However, mounting evidence reveals that an important aspect of cellular dysfunction can be inflicted by damage to other components of cells, such as the cell membrane and the collection of “organelles” inside it. And the nucleus is not the only organelle containing DNA.

Mitochondria generate energy and serve as the body’s cellular executioners. If a mitochondrion recognises that its cell’s DNA has been damaged, it may order the cell membrane to become permeable. Without the structure of the cell membrane, the cell breaks apart, its fragments carried away by immune cells. This is one mechanism behind “programmed cell death” – a controlled form of death, where the cell essentially presses its own self-destruct button (see “Self-destruct” image).

Irradiated mitochondrial DNA can suffer from strand breaks, base–pair mismatches and deletions in the code. In space-radiation studies, damage to mitochondrial DNA is a serious health concern as it can lead to mutations, premature ageing and even the creation of tumours. But programmed cell death can prevent a cancer cell from multiplying into a tumour. By disrupting the mitochondria of tumour cells, particle irradiation can compromise their energy metabolism and amplify cell death, increasing the permeability of the cell membrane and encouraging the tumour cell to self-destruct. Though a less common occurrence, membrane damage by irradiation can also directly lead to cell death.

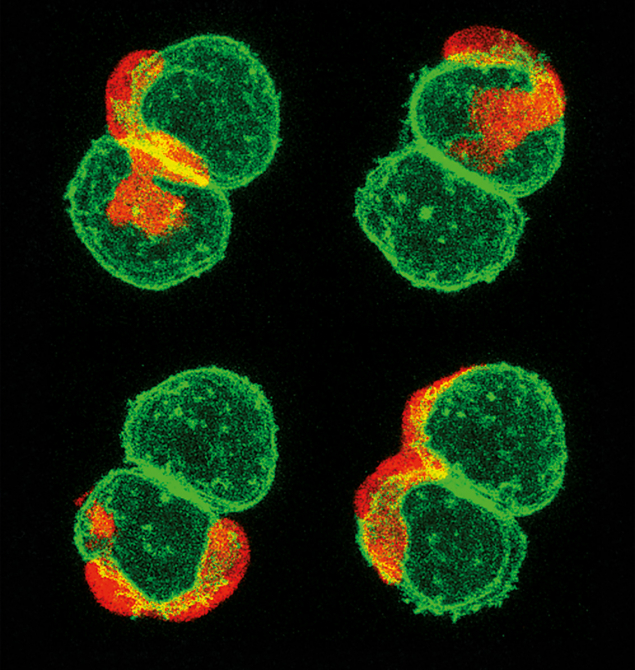

3. Bystander cells exhibit their own radiation response

For many years, radiobiology was driven by a simple assumption: only cells directly hit by radiation would be damaged. This view started to change in the 1990s, when researchers noticed something unexpected: even cells that had not been irradiated showed signs of stress or injury when they were near the irradiated cells. This phenomenon, known as the bystander effect, revealed that irradiated cells can send bio-chemical signals to their neighbours, which may in turn respond as if they themselves had been exposed, potentially triggering an immune response (see “Communication” image).

“Non-targeted” effects propagate not only in space, but also in time, through the phenomenon of radiation-induced genomic instability. This temporal dimension is characterised by the delayed appearance of genomic alterations across multiple cell generations. Radiation damage propagates across cells and tissues, and over time, adding complexity beyond the simple dose–response paradigm.

Although the underlying mechanisms remain unclear, the clustered ionisation events produced by carbon ions generate complex DNA damage and cell death, while largely preserving nearby, unirradiated cells.

4. Radiation damage activates the immune system

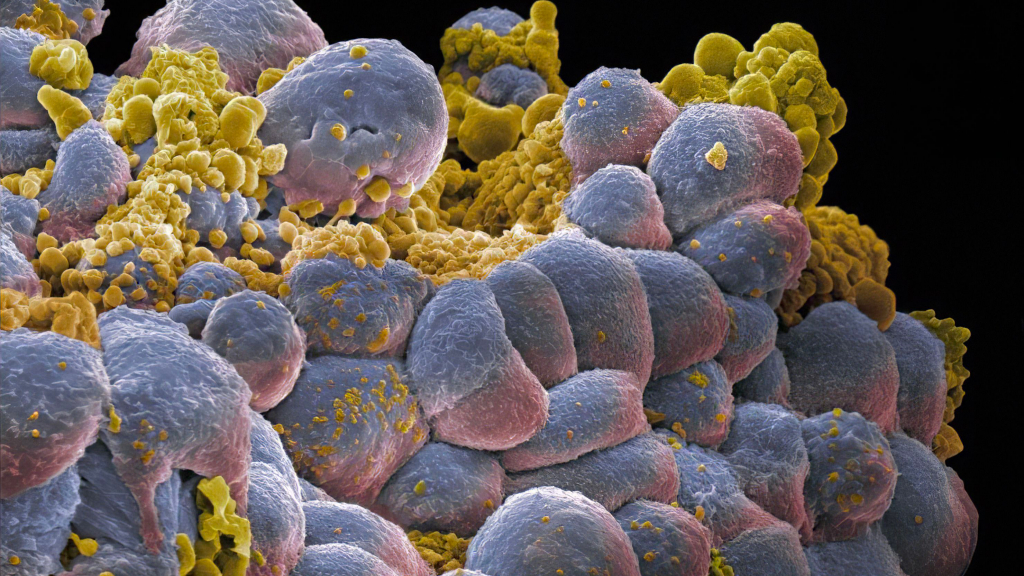

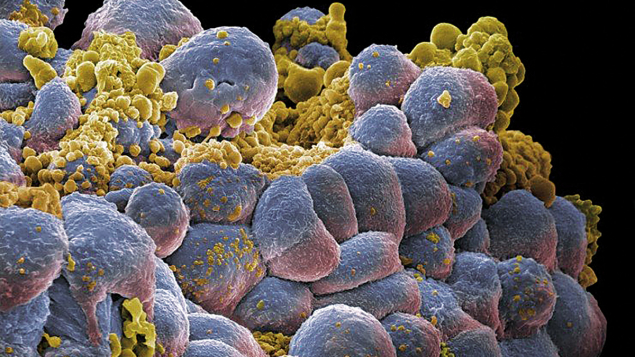

Cancer cells multiply because the immune system fails to recognise them as a threat (see “Immune response” image). The modern pharmaceutical-based technique of immunotherapy seeks to alert the immune system to the threat posed by cancer cells it has ignored by chemically tagging them. Radiotherapy seeks to activate the immune system by inflicting recognisable cellular damage, but long courses of photon radiation can also weaken overall immunity.

This negative effect is often caused by the exposure of circulating blood and active blood-producing organs to radiation doses. Fortunately, particle therapy’s ability to tightly conform the dose to the target and subject surrounding tissues to a minimal dose can significantly mitigate the reduction of immune blood cells, better preserving systemic immunity. By inflicting complex, clustered DNA lesions, heavy ions have the strongest potential to directly trigger programmed cell death, even in the most difficult-to-treat cancer cells, bypassing some of the molecular tricks that tumours use to survive, and amplifying the immune response beyond conventional radiotherapy with X-rays. This is linked to the complex, clustered DNA lesions induced by high-energy-transfer radiation, which triggers the DNA damage–repair signals strongly associated with immune activation.

These biological differences provide a strong rationale for the rapidly emerging research frontier of combining particle therapy with immunotherapy. Particle therapy’s key advantage is its ability to amplify immunogenic cell death, where the cell’s surface changes, creating “danger tags” to recruit immune cells to come and kill it, recognise others like it, and kill those too. This ability for particle therapy to mitigate systemic immunosuppression makes it a theoretically superior partner for immunotherapy compared to conventional X-rays.

5. Ultra-high dose rates protect healthy tissues

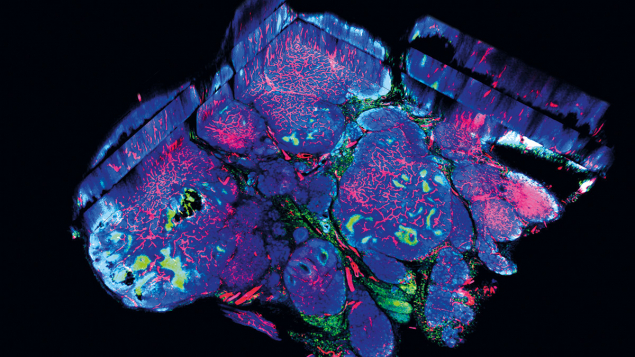

In recent years, the attention of clinicians and researchers has focused on the “FLASH” effect– a groundbreaking concept in cancer treatment where radiation is delivered at an ultra-high dose rate in excess of 40 J/kg/s. FLASH radiotherapy appears to minimise damage to healthy tissues while maintaining at least the same level of tumour control as conventional methods. Inflammation in healthy tissues is reduced, and the number of immune cells entering the tumour increased, helping the body fight cancer more effectively. This can significantly widen the therapeutic window – the optimal range of radiation doses that can successfully treat a tumour while minimising toxicity to healthy tissues.

Though the radiobiological mechanisms behind this protective effect remain unclear, several hypotheses have been proposed. A leading theory focuses on oxygen depletion or “hypoxia”.

As tumours grow, they outpace the surrounding blood vessels’ ability to provide oxygen (see “Oxygen depletion” image). By condensing the dose in a very short time, it is thought that FLASH therapy may induce transient hypoxia within normal tissues too, reducing oxygen-dependent DNA damage there, while killing tumour cells at the same rate. Using a similar mechanism, FLASH therapy may also preserve mitochondrial integrity and energy production in normal tissues.

It is still under investigation whether a FLASH effect occurs with carbon ions, but combining the biological benefits of high-energy-transfer radiation with those of FLASH could be very promising.