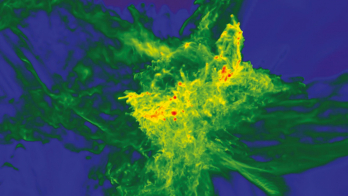

Supernovae are some of the most well-known astrophysical phenomena. The energies involved in these powerful explosions are, however, dwarfed by a gamma-ray burst (GRB). These extra-galactic explosions form the most powerful electromagnetic explosions in the universe and play an important role in its evolution. First detected in 1967, they consist of a bright pulse of gamma rays, lasting from several seconds to several minutes. This is followed by an afterglow emission that can be measured from X-rays down to radio energies for days or even months. Thanks to 60 years of observations of these events by a range of detectors, we now know that the longer GRBs are an extreme version of a core-collapse supernova. In GRBs, the death of the heavy star is accompanied by two powerful relativistic jets. If such a jet points towards Earth we can detect gamma-ray photons even for GRBs at distances of billions of light years. Thanks to detailed observations, the afterglow is now understood to be the result of synchrotron emission produced as the jet crashes into the interstellar medium.

After the detection of over 10,000 gamma-ray components of GRBs by dedicated gamma-ray satellites, the most common models associate the longer ones with supernovae. This has been confirmed thanks to detections of afterglow emission coinciding with supernova events in other galaxies. The exact characteristics that cause some heavy stars to produce a GRB remain, however, poorly understood. Furthermore, many open questions remain regarding the nature and origin of the relativistic jets and how the gamma rays are produced within them.

While the emission has been studied extensively in gamma rays, detections at soft X-ray energies are limited. This changed in early 2024 with the launch of the Einstein Probe (EP) satellite. EP is a novel X-ray telescope, developed by the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) in collaboration with ESA, the Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics and the Centre National d’Études Spatiales. EP is unique in its wide field of view (1/11th of the sky) in soft X-rays, made possible thanks to complex X-ray optics. As GRBs occur at random positions in the sky at random times, the large field of view increases its chance to observe them. Within its first year EP detected several GRB events, most of which challenge our understanding of them.

One of these occurred on 14 April 2024. It consisted of a bright flash of X-rays lasting about 2.5 minutes. The event was also observed by ground-based optical and radio telescopes that were alerted to its location in the sky by EP. These observations at lower photon energies were consistent with a weak afterglow together with the signatures from a relatively standard supernova-like event. The supernova emission showed it to originate from a star which, prior to its death, had already shed its outer layers of hydrogen and helium. Along with the spectrum detected by EP, the detection of an afterglow indicates the existence of a relativistic jet. The overall picture is therefore consistent with a GRB. However, a crucial part was missing: a gamma-ray component.

In addition, the emission spectrum observed by EP looks significantly softer as it peaks at keV rather than the 100s of keV energies typical for GRBs. The results hint at this being at an explosion that produced a relativistic jet which – for unknown reasons – was not energetic enough to produce the standard gamma-ray emission. The progenitor star therefore appears to bridge the stellar population which causes a “simple” core collapse supernova and those that produce GRBs.

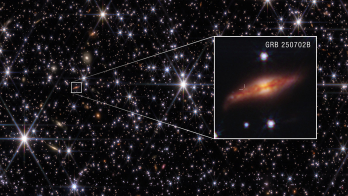

Another event, detected on 15 March 2024, produced soft X-rays consisting of six separate epochs spread out over 17 minutes. Here, a gamma-ray component was detected by NASA’s Swift BAT instrument, confirming it to be a GRB. However, unlike any other GRB, the gamma-ray emission started long after the onset of the X-ray emission. This lack of gamma-ray emission in the early stages is difficult to reconcile with standard emission models. There, the emission comes from a single uniform jet where the highest energies are emitted at the start when the jet is at its most energetic.

In their publication in Nature Astronomy, the EP collaboration suggests the possibility that the early X-ray emission comes from either shocks from the supernova explosion itself or from weaker relativistic jets preceding the main powerful jet. Other proposed explanations include complex jet structures and pose that EP observed the jet far away from its centre. In this explanation, the matter in the jet moves faster in the centre while at the edges its Lorentz factor (or velocity) is significantly slower, thereby producing a lower-energy longer-lasting emission, undetectable before the launch of EP.

Overall, the two detections appear to indicate that the GRBs detected over the last 60 years, where the emission was dominated by gamma rays, were only a subset of a more complex phenomenon. At a time where two of the most important instruments in GRB astronomy from the last two decades, NASA’s Fermi and Swift missions, are proposed to be switched off, EP is taking over an important role and opening the window to soft X-ray observations.

Further reading

Y Liu et al. 2025 Nat. Astron. 9 564.

H Sun et al. 2025 Nat. Astron. 9 1073.