Modern science visitor centres are equipped with the latest digital gadgets, offering breathtaking audio-visual experiences. But real objects hold a particular power to connect to people. Alison Boyle describes the importance of heritage in science.

One of the key challenges of communicating particle physics – particularly when preserving and presenting tangible artefacts – is the sheer scale of the endeavour. The infrastructure of particle physics has frequently been likened to cathedrals: great vaulted caverns built by the hands of many in search of truths about our universe. And even the major facilities are only one part in the international network of particle physics. Museums, which are also often likened to cathedrals, weren’t typically designed with gigantic and internationally distributed artefacts in mind. And that’s before we consider the objects of study: you can’t display a particle in a glass case. So how can we find tangible ways to represent abstract physical phenomena? What does it mean to represent the work of the thousands of people involved in today’s particle-physics projects? And is it possible to capture a fleeting moment of discovery for posterity?

Sometimes, those fleeting moments are best captured by ephemeral objects. Something that might seem mundane or throwaway can provide eloquent insights into the real life of physics. The announcement of the discovery of the Higgs Boson at CERN on 4 July 2012 was recorded in several formats, notably the film footage of Peter Higgs wiping away a tear in CERN’s main auditorium as the ATLAS and CMS teams announced the discovery of the particle whose existence he, François Englert and Robert Brout had predicted decades before.

A material memorial of the Higgs-boson discovery is the champagne bottle emptied by Higgs and John Ellis the night before the announcement. In fact, the quiet and modest Higgs usually prefers London Pride beer; unfortunately, the can that he drank on his flight home from Geneva after the announcement was not saved for posterity. But the champagne bottle also speaks to a common practice at CERN: around the site, particularly in the CERN Control Centre, there are arrays of empty bottles, opened in celebration of events including the LHC start-up, first physics collisions, major publications and other milestones.

Familiar yet unexpected objects such as the champagne bottle in the context of a display about physics can pique visitors’ interest and encourage them to move on to more complex-looking displays that they might otherwise pass by. As such, Higgs’ champagne bottle featured in the Collider exhibition (see above picture) produced by the London Science Museum in 2013 and another bottle is part of CERN’s heritage collection – a curated assortment of more than 200 objects that encapsulate CERN’s history.

Magic moments

Connecting to newsworthy moments or well-known people is usually a successful draw for visitors. Capitalising on the global success of the movie Oppenheimer, this year the Bradbury Science Museum at Los Alamos developed an exhibition of Oppenheimer-related artefacts, including his own copy of the Bhagavad Gita. At CERN Science Gateway, Tim Berners-Lee’s NeXT computer – used to host the first website – creates an immediate talking point for visitors who can barely imagine life without the web, despite the object itself being literally a black box.

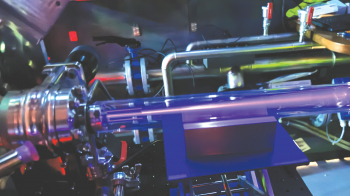

That said, it is rare for a scientific or technological artefact to be a “show piece” that would attract visitors in its own right, in the same way that they would queue to see a famous artwork. The Antikythera mechanism at the National Archaeological Museum in Athens, Galileo’s telescopes at the Museo Galileo in Florence, or the Apollo 11 command module at the National Air and Space Museum in Washington are not representative of the types of material generally found in science heritage collections. Most science-related objects are not that easy for non-specialists to engage with; to the uninitiated eye the tools of particle physics mostly look like wiring and plumbing. Exhibition developers therefore usually adopt the “key pieces” approach advocated by Dutch curator Ad Maas: setting objects in the context of an overall narrative and a rich array of materials including photographs, documents, film, audio and personal testimony brings them to life and allows developers to layer information for different audience tastes and interest levels. Thanks to CERN’s archives and heritage collection, there is a wide range of material to draw from.

Using the key-pieces approach, a single small part can be revealing of a much larger whole: for example, by following the “life story” of a lead tungstate crystal used in the CMS electromagnetic calorimeter – which was also featured at the Collider exhibition – we gain insights into the decades-long design and planning process for the CMS detector, and an adventure in production and testing that takes us on a journey via Moscow, Shanghai and Rome (with a detour to the UBS bank vaults in Zurich). The physical nature of the object itself reflects its design and production history, while also illustrating the phenomena of particle decay and scintillation. At CERN, you’ll find displays of crystals like these around the site, in public and private spaces.

Much of the scientific heritage of the 20th and 21st centuries was originally preserved by practitioners with a sixth sense of “this might be useful someday” rather than by professional curators. Today, CERN has detailed archival and heritage collection policies that offer guidance as to what kinds of material might be worth keeping for posterity. Of course it’s impossible to keep everything; we can’t predict for certain what avenues future historians might be interested in exploring, or what kinds of objects will be used to popularise science. But by preserving storehouses of memories, we might be keeping some building blocks for the cathedrals of a future age.