Flash! The Hunt for the Biggest Explosions in the Universe by Govert Schilling, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0521800536, £18.95 ($28.00).

The Biggest Bangs: The Mystery of Gamma-Ray Bursts, The Most Violent Explosions in the Universe by Jonathan I Katz, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0195145704, £18.95 ($28.00).

Our understanding of fundamental physics has historically been closely tied to observations of the cosmos. These two books tell the unfinished story of one of the greatest challenges in contemporary astrophysics: the origin of gamma-ray bursts (GRBs), which appear to be the most energetic events in the universe. It’s an exciting story and well worth telling, especially to the lay public.

In 1687, Isaac Newton published his universal theory of gravitation. For well over 200 years it reigned supreme, because it appeared to describe completely all of the observed motions of the planets and other astronomical objects in the heavens. As it turned out, of course, even this enormous advance – achieved by “standing on the shoulders of giants”, as Newton famously remarked – is by no means the entire story. And what a story it has turned out to be. For even though Newtonian dynamics works most of the time, it lacks the capacity to describe – let alone predict – many of the gravitational phenomena that are at the frontiers of research in astrophysics today.

In 1915, Einstein published his general theory of relativity. In attempting to explain a discrepancy between theory and observation in the perihelion of Mercury, and by incorporating into Newtonian dynamics his special theory of relativity, Einstein created a dynamics that revolutionized our understanding of the universe. Earlier, in 1905, Einstein taught us that energy and mass are equivalent, and he introduced the concept of space-time. Then in 1915, he showed that the stress-energy tensor of space-time was a response to its curvature – or, in John Wheeler’s phrase, “matter tells space-time how to bend, and curved space-time tells matter how to move.” Einstein’s theory went on to predict the existence of phenomena such as the bending of light in a gravitational field, gravitational radiation, neutron stars and black holes, among others. Here, as in much of modern science, the truth really is stranger than fiction.

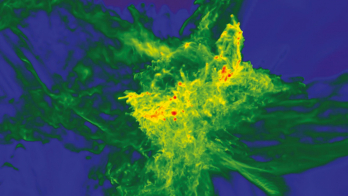

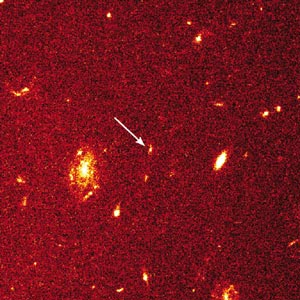

Gamma-ray bursters are one of the strangest phenomena of all. They were discovered by accident in the late 1960s, using satellites created to search for violations of the nuclear test-ban treaty. Since then they have been a source of great mystery, and have had their share of scientific competition and controversy. We now know that GRBs, which occur at a rate of about one per day and are uniformly distributed over the sky, are at cosmological distances and must be by far the most energetic phenomena in the universe since the Big Bang itself. However, reaching these conclusions took 30 years and the combined efforts of the worldwide astrophysical community, using a panoply of the most modern instruments and theoretical developments, as well as rapid communication via the Internet and the Web.

Visual and highly accessible, Schilling’s book is a masterpiece of lay scientific reporting. He is the author of more than 20 previous books and hundreds of articles on astronomical subjects (it shows; the prologue alone is almost worth the price of the book). Beginning with the initial discovery of GRBs by Ray Klebesadel and Roy Olson circa 1970, the reader is artfully led down the path that science often takes – one of tantalizing data, missteps, blind alleys, wishful thinking, raging competition, broken dreams – and for some, great success. Along the way we meet all of the major players in the GRB drama, and are skillfully introduced to all of the relevant scientific history, theoretical concepts and experimental findings. By the end, we’ve learned how it was determined that GRBs are uniform across the sky (from the BATSE detector on the Compton Gamma Ray Observatory), how it was determined that GRBs are at cosmological distances (by learning, using the BeppoSAX satellite, how to observe GRB afterglows at optical and radio wavelengths, which in turn allowed the determination of redshifts), and how it was concluded that these objects are so enormously energetic.

On these last issues, the fact that GRBs wink in and out of existence so quickly made it imperative to share the position data from BATSE and BeppoSAX as rapidly and broadly as possible, so that the afterglows would be bright enough for spectral analysis. The Internet and the Web provided the means to do this, and the data provided the basis for the fully automatic wide-angle optical search systems known as LOTIS and ROTSE. The theoretical constructs discussed include the relativistic fireball model and magnetars, among others. My only quibble is that given the obvious care that the author devoted to his task, it’s too bad the proof-reading was not better, as there are quite a few typos. However, the book is very well translated from the Dutch, and makes for superb reading.

Jonathan Katz’s book is differently oriented. Rather than spend as much time on the historical aspects, he devotes a great deal of effort to elucidating the science surrounding GRBs, as well as the technical details of various detection systems. My opinion is that while these parts are very well done, it is all rather too much for a lay reader. Instead it might be very useful for classes of undergraduate physics or astronomy students. The kinds of explanations that Katz provides are not often found in the textbooks, and would provide excellent supplementary information. However, there is a significant amount of complaining about NASA and NSF decision-making, as well as gratuitous remarks about other people’s careers. This material does nothing to advance the book’s main purpose, and would have been much better left out.

Both books contain very useful glossaries, guides to other sources and literature, and are well indexed. Each has a great deal to offer to its respective audience.