Forty years after his PhD studies at the ISR, former astronaut Ernst Messerschmidreturned to CERN to talk about his time in space and the imperatives for space flight.

Image credit: DLR, CC-BY 3.0.

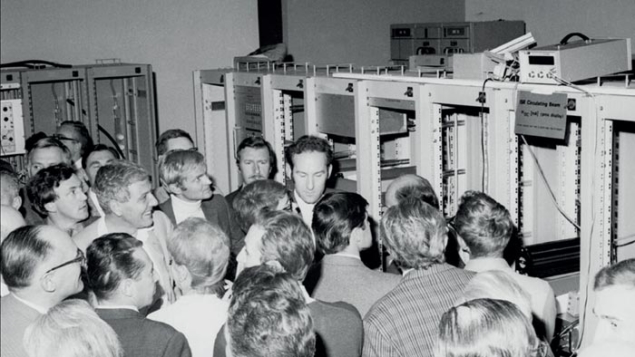

Ernst Messerschmid first arrived at CERN as a summer student in 1970, in the midst of preparations for the start up of the Intersecting Storage Rings (ISR). The studies that he did on beam pick-ups in this ground-breaking particle collider formed the topic of his diploma thesis – but he was soon back at the laboratory as a fellow, sharing in the excitement of seeing injection of the first beams on 29 October that same year. This time he worked on simulations of longitudinal beam instabilities, the subject of his PhD thesis. By the time he came back to CERN some 40 years later to give a colloquium in May this year, he was one of the few people to have worked in space and he had even had a hand in training another former CERN fellow, Christer Fuglesang, before he also flew into space.

A self-confessed “country boy”, Messerschmid grew up in Reutlingen in south-western Germany, training first as a plumber and then attending the Technisches Gymnasium in Stuttgart. An aptitude for mathematics turned him towards more academic pursuits and after military service he enrolled at the universities of Tübingen and Bonn. Coming to CERN then as a summer student opened up a new world – an international lab set among the French-speaking communities on the Franco-Swiss border near Geneva. He was on the first steps of the journey that would take him much further afield – into space.

Following his fellowship at the ISR, Messerschmid gained his doctorate from the University of Freiburg. After further experience in accelerators at Brookhaven National Laboratory, he started work at DESY in 1977 optimizing the alternating-gradient magnets for the PETRA electron–positron collider. He looked set for a career in accelerator physics but while deciding on his future he spotted an advert in the newspaper Die Zeit: “Astronauts wanted.”

The questions were easy for a ‘CERNois’ to answer. The challenge came afterwards.

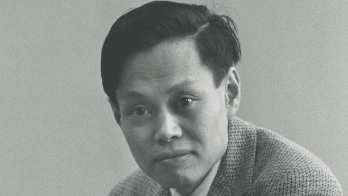

Ernst Messerschmid

Messerschmid had by chance come across ESA’s first astronaut selection campaign. “There were five boxes to tick,” he recalls. “Scientific training, good health, psychological stability, language skills and experience in an international environment. Being prepared by my time at CERN, I could tick them all.” Out of some 7000 applicants, he was among five selected in Germany, of whom three eventually went into space: Ulf Merbold was first, as an ESA astronaut, with Reinhard Furrer and Messerschmid following. “The questions were easy for a ‘CERNois’ to answer,” he says. “The challenge came afterwards.”

So, Messerschmid left the world of particle accelerators and in 1978 went to work on satellite-based, search-and-rescue communication systems at the German Aerospace Test and Research Institute (DFVLR), the precursor of the German Aerospace Centre (DLR). He was selected for training as a science astronaut in 1983. Two years later, after scientific training at various universities and industrial laboratories, as well as flight training at ESA and NASA, he was assigned as a payload specialist on the first German Spacelab mission, D1, aboard the Challenger space shuttle. With two NASA pilots, three NASA mission specialists and three payload specialists from Europe, this was the largest crew to fly on the space shuttle. Joining Messerschmid from Europe were his fellow German, Reinhard Furrer, and Wubbo Ockels, from the Netherlands. It was the first Spacelab mission in which payload activities were controlled from outside the US. It was also the last flight of the Challenger before the disaster in January 1986.

Working in space

Between 30 October and 6 November 1985, Ernst and his colleagues performed more than 70 experiments. This was the first series to take full advantage of the “weightless” conditions on Spacelab, covering a range of topics in physical, engineering and life-science disciplines. “These were not just ‘look and see’ experiments,” Messerschmid explains. “We studied critical phenomena. With no gravity-driven convection and no sedimentation we could make different alloys – for example, mixing a heavy metal with aluminium. In other experiments we grew uniform, large single crystals of pharmaceuticals for X-ray crystallography studies.”

It was the experiments – more than the launch and distance from Earth – that proved to be the most stressful. “There were 100 or so professors and some 200 students who were dependent on the data we were collecting,” Messerschmid says. “We worked 15–18 hours a day. There was not much time to look out of the window!” But look out of the window he did, and the view of Earth was to leave a lasting impression, not only because of its beauty but also because of the cautionary signs of exploitation. He saw smoke from fires in the rainforests and the bright lights at night over huge urban areas. “Our planet is overcrowded,” he observes. “We can’t continue like this.”

Since 2005, Messerschmid has been back at Stuttgart as chair of astronautics and space stations

After his spaceflight, Messerschmid moved to the University of Stuttgart, where he became director of the Space Systems Institute, doing research and lecturing on space and transportation systems, re-entry vehicles and experiments in weightlessness. He went on to be dean of the faculty of aerospace at Stuttgart and the university’s vice-president for science and technology before becoming head of the European Astronaut Centre in Cologne in 2000. There, he was involved in training Fuglesang, who has since flown twice aboard a space shuttle to the International Space Station. Since 2005, Messerschmid has been back at Stuttgart as chair of astronautics and space stations.

In the meantime, he renewed contact with CERN when he joined Gerald Smith from Pennsylvania State University and others in 1996 on a proposal for a general-purpose, low-energy antiproton facility at the Antiproton Decelerator, based on a Penning trap. Messerschmid and Smith were interested in using antiprotons and in particular the decay chain of the annihilation products for plasma heating in a concept for an antimatter engine. A letter-of-intent described an experiment to measure the energy deposit of proton–antiproton annihilation products in gaseous hydrogen or xenon and compare it with numerical simulations. Messerschmid’s student, Felix Huber, worked at CERN for several months but in the end nothing came of the proposal.

Back in Stuttgart, Messerschmid continues to teach astronautics and – as in the colloquium at CERN – to spread the word on the value of spaceflight for knowledge and innovation. “We fly a mission,” he says, “and afterwards, as professors, we become ‘missionaries’ – ambassadors for science and innovation.” His “mission statement” for spaceflight has much in common with that of CERN, with three imperatives: to explore – the cultural imperative; to understand – the scientific imperative; and to unify – the political imperative. While the scientific imperative is probably self-evident, the cultural imperative recognizes the human desire to learn and the need to inspire the next generation, and the political imperative touches on the value of global endeavours without national boundaries – all aspects that are close to the hearts of the founders of CERN and their successors.

So what advice would he give a young person, perhaps coming to CERN as a summer student, as he did 40 years ago? The plumber-turned-accelerator physicist who became an astronaut reflects for a few moments. “Thinking more in terms of jobs,” he replies, “consider engineering – physicists can also become engineers.” Then he adds: “Physicists live on the technologies that engineers produce. Engineers solve the differential equations, they makes theories a reality.” Who knows, one day the antimatter plasma-heating for propulsion might become a reality.