Seven ambitious, diverse and technically complex colliders have been proposed as options for CERN’s next large-scale collider project: CLIC, FCC-ee, FCC-hh, LCF, LEP3, LHeC and a muon collider. The European Strategy Group tasked a working group drawn from across the field (WG2a) to compare these projects on the basis of their technical maturity, performance expectations, risk profiles, and schedule and cost uncertainties. This evaluation is based on documentation submitted for the 2026 update to the European Strategy for Particle Physics (CERN Courier May/June 2025 p8). With WG2a’s final report now published, clear-eyed comparisons can be made across the seven projects.

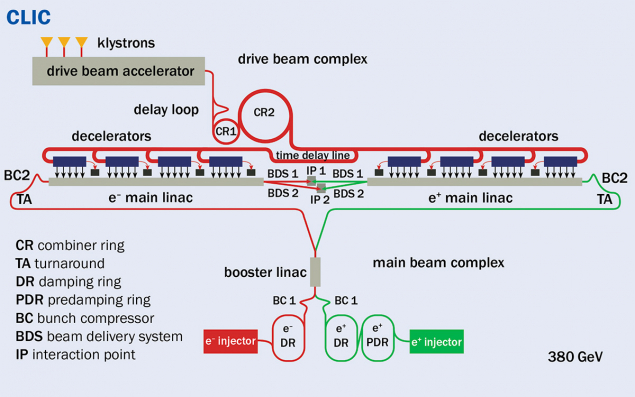

CLIC

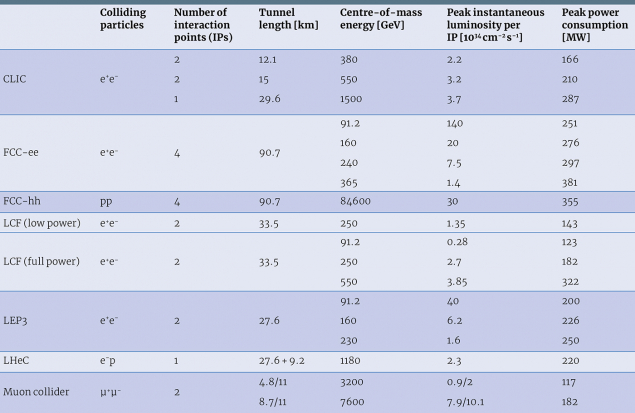

The Compact Linear Collider (CLIC) is a staged linear collider that collides a polarised electron beam with an unpolarised positron beam at two interaction points (IPs) which share the luminosity (see figures and “Design parameters” table). It is based on a two-beam acceleration scheme where power from an intense 1 GHz drive beam is extracted and used to operate an X-band 12 GHz linac with accelerating gradients from 72 to 100 MV/m. The potential of two-beam acceleration to achieve high gradients enables a compact linear-collider footprint. Collision energies between 380 GeV and 1.5 TeV can be achieved with a total tunnel length of 12.1 or 29.4 km, respectively. The proof-of-concept work at the CLIC Test Facility 3 (CTF3) has demonstrated the principles successfully, but not yet at a scale representative of a full collider. A larger-scale demonstration with higher beam currents and more accelerating structures would be necessary to achieve full confidence in CLIC’s construction readiness.

The project has a well developed design incorporating decades of effort, and detailed start-to-end (damping ring to IP) simulations have been performed indicating that CLIC’s design luminosity is achievable. CLIC requires tight fabrication and alignment tolerances, active stabilisation, and various feedback and beam-based correction concepts. Failure to achieve all of its tight specifications could translate into a luminosity reduction in practical operation. CLIC still requires a substantial preparation phase and territorial implementation studies, which introduces some uncertainty on its proposed timeline.

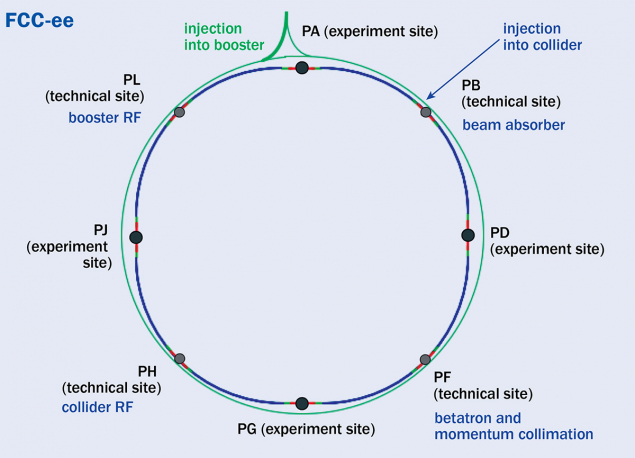

FCC-ee

The electron–positron Future Circular Collider (FCC-ee) is the proposed first stage of the integrated FCC programme. This double-ring collider, with a 90.7 km circumference, enables collision centre-of-mass energies up to 365 GeV and allows for four IPs.

FCC-ee stands out for its level of detail and engineering completeness. The FCC Feasibility Study, including a cost estimate, was recently completed and has undergone scrutiny by expert committees, CERN Council and its subordinate bodies (CERN Courier May/June 2025 p9). This preparation translates into a relatively high technical-readiness level (TRL) across major subsystems, with only a few lower-level/lower-cost elements requiring targeted R&D. The layout has been chosen after a detailed placement study considering territorial, geological and environmental constraints. Dialogue with the public and host-state authorities has begun.

Performance estimates for FCC-ee are considered robust: previous experience with machines such as LEP, PEP-II, DAΦNE and SuperKEKB has provided guidance for the design and bodes well for achieving the performance targets with confidence. In terms of readiness, FCC-ee is the only project that already possesses a complete risk-management framework integrated into its construction planning.

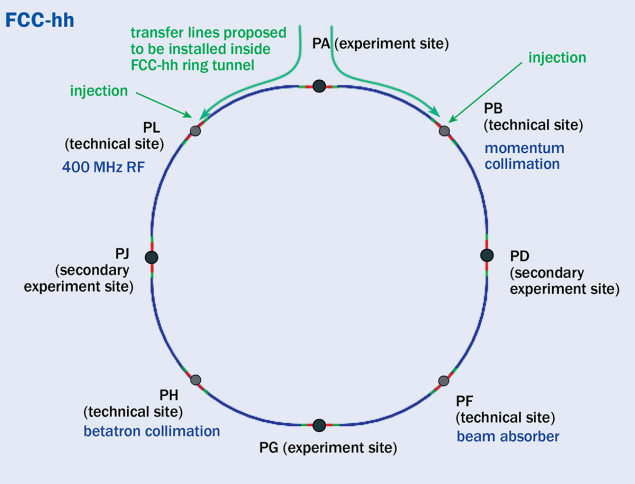

FCC-hh

The hadron version of the Future Circular Collider (FCC-hh) would provide proton–proton collisions up to a nominal energy of 85 TeV – the maximum achievable in the 90.7 km tunnel for the target dipole field of 14 T. As a second stage of the integrated FCC programme, it would occupy the tunnel after the removal of FCC-ee, and so could potentially start operation in the mid-2070s. FCC-hh’s cost uncertainty is currently dominated by its magnets. The baseline design uses superconducting Nb3Sn dipoles operating at 1.9 K, though high-temperature superconducting (HTS) magnets could reduce the electricity consumption or allow higher fields and beam energies for the same power consumption. Both technology approaches are active research directions of Europe’s high-field magnet programme.

The required Nb3Sn technology is progressing steadily, but still needs 15 to 20 years of R&D before industry-ready designs could be available. HTS cables satisfying the specifications required for the magnets of a high-luminosity collider, although extremely promising, are at an even earlier stage of development. If FCC-hh were to proceed as a standalone project, operations could possibly start around 2055 from a technical perspective. In that case the magnets would need to be based on Nb3Sn technology, as HTS accelerator-magnet technology is not expected to be available in that timeframe.

FCC-hh’s performance expectations draw strength from the LHC experience, though the achievable integrated luminosity would depend on the required “luminosity levelling” scenario that might be determined by pile-up control at the experiments. Luminosity levelling is a technique used in particle colliders such as the LHC to keep the instantaneous luminosity approximately constant at the maximum level compatible with detector readout, rather than letting it start very high and then decay rapidly.

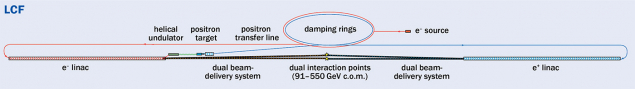

LCF

The Linear Collider Facility (LCF) is a linear electron-positron collider, based on the design of the International Linear Collider (ILC), in a 33.5 km tunnel with two IPs sharing the pulses delivered by the collider and with double the repetition rate of ILC. The first phase aims at a centre-of-mass energy of 250 GeV, though the tunnel is sized to accommodate an upgrade to 550 GeV. LCF’s main linacs incorporate 1.3 GHz bulk-Nb superconducting radiofrequency (SRF) cavities for acceleration, operated at an average gradient of 31.5 MV/m and a cavity quality factor twice that of the ILC design at the same accelerating gradient. The quality factor of an RF cavity is a measure of how efficiently the cavity stores electromagnetic energy compared with how much it loses per cycle. LCF can deliver polarised positron and electron beams. Its engineering definition is solid and its SRF technology widely used in several operational facilities, most prominently at the European XFEL, however, the specific performance targets exceed what has been routinely achieved in operation to date. Demonstrating this combination of high gradient and high quality remains a central R&D requirement.

Several lower-TRL components – such as the polarised positron source, beam dumps and certain RF systems – also require focused development. Final-focus performance, which is more critical in linear colliders compared to circular colliders, relies on validation at KEK’s Accelerator Test Facility 2, which is being extended and upgraded. The overall schedule is credible but depends on securing the needed R&D funding and would require a preparation phase including detailed territorial implementation studies and geological investigations.

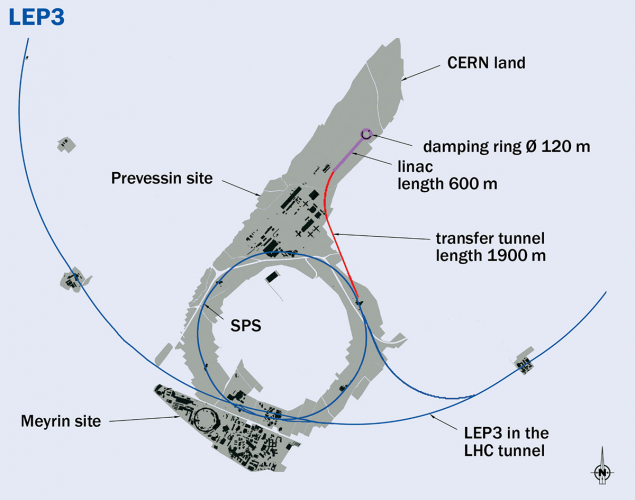

LEP3

The Large Electron Positron collider 3 (LEP3) proposal explores the reuse of the existing LEP/LHC tunnel for a new circular electron–positron (e+e–) collider. LEP3 has two IPs and the potential for collision energies ranging from 91 to 230 GeV; its luminosity performance and energy range are limited by synchrotron radiation emission, which is more severe than in FCC-ee due to its smaller radius and the limited space available for the SRF installation.

The LEP3 proposal is not yet based on a conceptual or technical design report. Its optics and performance estimates depend on extrapolations from FCC-ee and earlier preliminary studies, and the design has not undergone full simulation-based validation. The current design relies on HTS combined quadrupole and sextupole focusing magnets. Though they would be central to LEP3 achieving a competitive luminosity and power efficiency, these components currently have low TRL scores.

Although tunnel reuse simplifies territorial planning, logistics such as dismantling HL-LHC components introduce non-trivial uncertainties for LEP3. In the absence of a conceptual design report, timelines, costs and risks are subject to significant uncertainty.

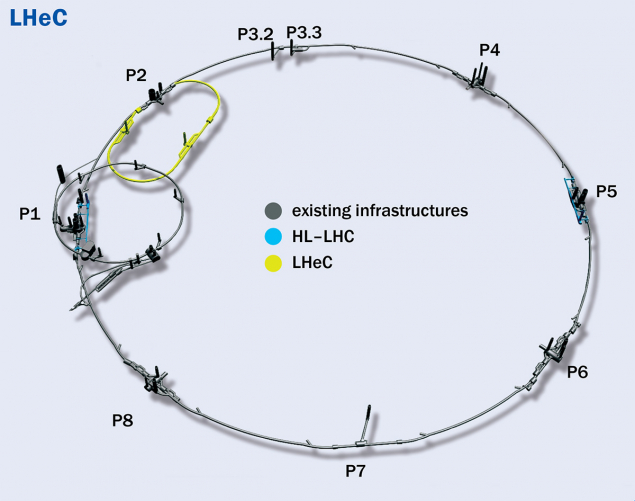

LHeC

The Large Hadron–Electron Collider (LHeC) proposal incorporates a novel energy-recovery linac (ERL) coupled to the LHC. High-luminosity collisions take place between a 7 TeV proton beam from the HL–LHC and a high-intensity 50 GeV electron beam accelerated in the new ERL. The LHeC ERL would consist of two linacs based on bulk-Nb SRF 800 MHz cavities, connected by recirculation arcs, resulting in a total machine circumference equal to one third that of the LHC. After acceleration, the beam will collide with the proton beam and will be successively decelerated in the same SRF cavities, “giving back” the energy to the RF system.

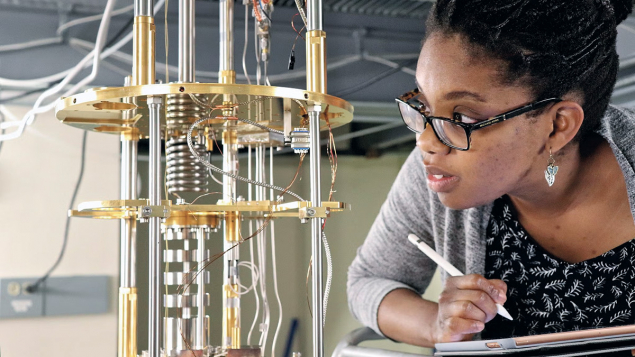

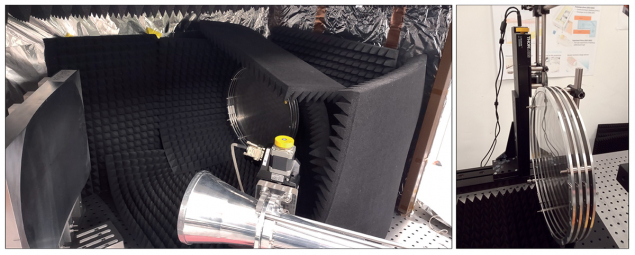

The LHeC’s performance depends critically on demonstrating high-current, multi-pass energy recovery at multi-GeV energies, which has not yet been demonstrated. The PERLE (Powerful Energy Recovery Linac for Experiments) demonstrator under construction at IJCLab in Orsay will test critical elements of this technology. The main LHeC performance uncertainties relate to the efficiency of energy recovery and beam-loss control of the electron beam during the deceleration process after colliding with the proton beam. Schedule, cost and performance will depend on the outcomes demonstrated at PERLE.

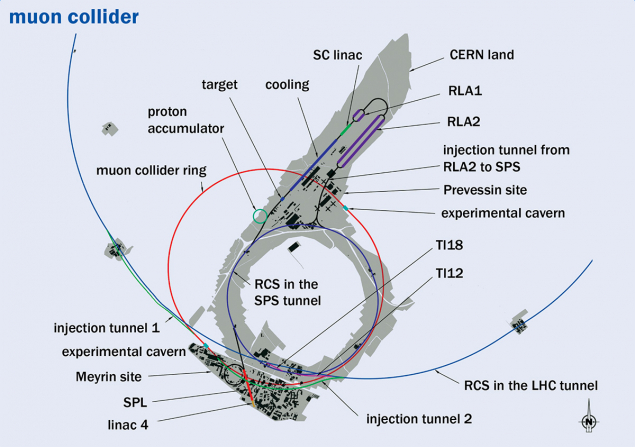

Muon collider

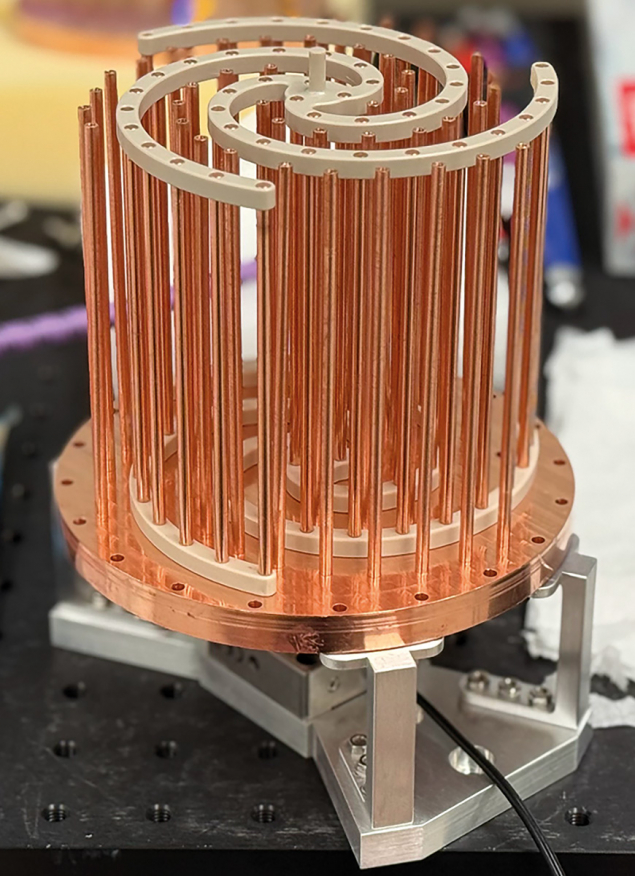

Among the large-scale collider proposals submitted to the European Strategy for Particle Physics update, a muon collider offers a potentially energy-efficient path toward high-luminosity lepton collisions at a centre-of-mass energy of 10 TeV. The larger mass of the muons, as compared with electrons and positrons, reduces the amount of synchrotron radiation emitted in a circular collider of a given energy and radius. The muons are generated from the decays of pions produced by the collision of a high-power proton beam with a target. “Ionisation cooling” of the muon beams via energy loss in absorbers made of low-atomic-number materials and acceleration by means of high-gradient RF cavities immersed in strong magnetic fields is required to reduce the energy spread and divergence of this tertiary beam. Fast acceleration is then needed to extend the muons’ lifetimes in the laboratory frame, thereby reducing the fraction that decays before collision. To achieve this, novel rapid-cycling synchrotrons (RCSs) could be installed in the existing SPS and LHC tunnels.

Neutrino-induced radiation and technological challenges such as high-field solenoids and operating radiofrequency cavities in multi-Tesla magnetic fields present major challenges that require extensive R&D. Demonstrating the required muon cooling at the required level in all six dimensions of phase space is a necessary ingredient to validate the performance, schedule and cost estimates.

WG2a’s comparison, together with the analysis conducted by the other working groups of the European Strategy Group, notably that of WG2b, which is providing an assessment of the physics reach of the various proposals, provides vital input to the recommendations that the European particle-physics community will make for securing the future of the field.