Raphael Granier de Cassagnac discusses opportunities for particle physicists in the gaming industry.

“Confucius famously may or may not have said: ‘When I hear, I forget. When I see, I remember. When I do, I understand.’ And computer-game mechanics can be inspired directly by science. Study it well, and you can invent game mechanics that allow you to engage with and learn about your own reality in a way you can’t when simply watching films or reading books.”

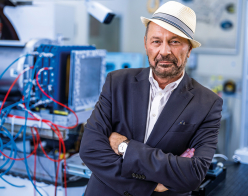

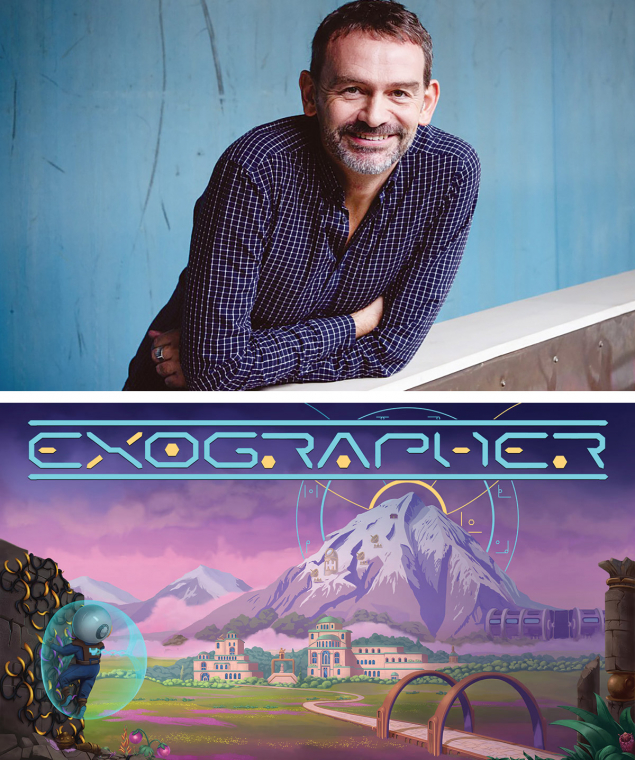

So says Raphael Granier de Cassagnac, a research director at France’s CNRS and Ecole Polytechnique, as well as member of the CMS collaboration at the CMS. Granier de Cassagnac is also the creative director of Exographer, a science-fiction computer game that draws on concepts from particle physics and is available on Steam, Switch, PlayStation 5 and Xbox.

“To some extent, it’s not too different from working at a place like CMS, which is also a super complicated object,” explains Granier de Cassagnac. Developing a game often requires graphic artists, sound designers, programmers and science advisors. To keep a detector like CMS running, you need engineers, computer scientists, accelerator physicists and funding agencies. And that’s to name just a few. Even if you are not the primary game designer or principal investigator, understanding the

fundamentals is crucial to keep the project running efficiently.

Root skills

Most physicists already have some familiarity with structured programming and data handling, which eases the transition into game development. Just as tools like ROOT and Geant4 serve as libraries for analysing particle collisions, game engines such as Unreal, Unity or Godot provide a foundation for building games. Prebuilt functionalities are used to refine the game mechanics.

“Physicists are trained to have an analytical mind, which helps when it comes to organising a game’s software,” explains Granier de Cassagnac. “The engine is merely one big library, and you never have to code anything super complicated, you just need to know how to use the building blocks you have and code in smaller sections to optimise the engine itself.”

While coding is an essential skill for game production, it is not enough to create a compelling game. Game design demands storytelling, character development and world-building. Structure, coherence and the ability to guide an audience through complex information are also required.

“Some games are character-driven, others focus more on the adventure or world-building,” says Granier de Cassagnac. “I’ve always enjoyed reading science fiction and playing role-playing games like Dungeons and Dragons, so writing for me came naturally.”

Entrepreneurship and collaboration are also key skills, as it is increasingly rare for developers to create games independently. Universities and startup incubators can provide valuable support through funding and mentorship. Incubators can help connect entrepreneurs with industry experts, and bridge the gap between scientific research and commercial viability.

“Managing a creative studio and a company, as well as selling the game, was entirely new for me,” recalls Granier de Cassagnac. “While working at CMS, we always had long deadlines and low pressure. Physicists are usually not prepared for the speed of the industry at all. Specialised offices in most universities can help with valorisation – taking scientific research and putting it on the market. You cannot forget that your academic institutions are still part of your support network.”

Though challenging to break into, opportunity abounds for those willing to upskill

The industry is fiercely competitive, with more games being released than players can consume, but a well-crafted game with a unique vision can still break through. A common mistake made by first-time developers is releasing their game too early. No matter how innovative the concept or engaging the mechanics, a game riddled with bugs frustrates players and damages its reputation. Even with strong marketing, a rushed release can lead to negative reviews and refunds – sometimes sinking a project entirely.

“In this industry, time is money and money is time,” explains Granier de Cassagnac. But though challenging to break into, opportunity abounds for those willing to upskill, with the gaming industry worth almost $200 billion a year and reaching more than three billion players worldwide by Granier de Cassagnac’s estimation. The most important aspects for making a successful game are originality, creativity, marketing and knowing the engine, he says.

“Learning must always be part of the process; without it we cannot improve,” adds Granier de Cassagnac, referring to his own upskilling for the company’s next project, which will be even more ambitious in its scientific coverage. “In the next game we want to explore the world as we know it, from the Big Bang to the rise of technology. We want to tell the story of humankind.”